Remittances to aging parents widespread, motives differ

Don’t be a stranger

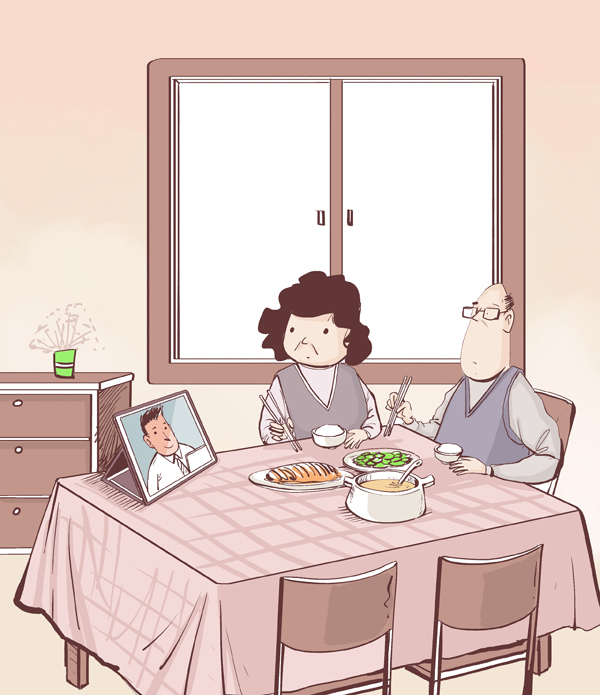

Cartoon by Gou Ben; Poem by Long Yuan

Though society changes,

With each passing day,

Filial piety remains

A duty to obey.

It doesn’t matter if you work too much,

Keep your family close

And stay in touch.

Breaking down boundaries of spacetime,

With the power of Facetime.

As the population ages,

It is vital to study the remittance of wage.

Theoretical research is needed for problem correction,

But you cannot ignore kinship and domestic affection.

In a developing country like China, remittances from children to their parents are an important means of resource allocation. Issues like changing family values and population aging pose new challenges for scholars and leaders as they strive to formulate policies to care for the nation’s elderly. Also, pensions and other public strategies have a closer relationship with remittances. But opinions vary on how to ensure payments are transferred while keeping remittances within families. The following article looks at the motivation of intergenerational transfers based on the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS).

Formation

Remittances are a major component of intergenerational relations. Statistics show at least half of children in developed countries send a portion of their incomes to their parents, while the percentage in China is even higher.

In China and other developing countries, infrastructure distribution is unequal and incomplete, so many families rely on unofficial support for income. For thousands of years, the Confucian notion of filial piety has been rooted in the mind of the Chinese people. In practice this means children have a moral obligation to support their parents with money and time.

A 2008 CHARLS study found that 86 percent of the rural elderly surveyed are supported by their adult children, and 10 percent have saved for retirement, but only 2 percent believe they have saved enough.

In 2011, the survey found that nearly 68 percent of people hope to live with their children after retirement and believe their children will support them economically. However, family values have changed considerably due to the social and economic shifts brought by the reforms that started in the 1970s. The idea of children as a means of support in the old age is being challenged.

A growing economy produces smaller family units. Populations become increasingly mobile, and the rise of individualistic tendencies encourages youth to leave home in search of opportunity. People are no longer constrained by the tradition that they must live with or close to their parents. Though the growing distance does not necessarily affect remittances, it crucially decreases care and companionship. Mature financial markets, old-age organizations and social welfare institutions in developed countries ensure elderly people a good quality of life, while seniors in China still rely mostly on their children.

In such an atmosphere, it is necessary to look at the motivations for remittances between children and parents because diverse motives need to be addressed with different public strategies. As American economist Gary Baker argues, remittances driven by altruism would contribute to coordinated family relations and equalize average incomes. However, if families are dominated by an exchange relationship, the poor and socially vulnerable aging population is less likely to gain support from their children.

The latest research has drawn a more detailed distinction between altruism and the exchange relationship. In this thesis, the motivation of altruism means that children give income or time out of concern for the wellbeing of their parents without expecting anything in return. Exchange relationships can be subdivided into direct and indirect exchanges. The following hypotheses illustrate various motivations for intergenerational remittances.

Altruism hypothesis

In developing countries, immature financial organizations and incomplete social welfare systems are hardly sufficient to ensure the wellbeing of the aging population. In addition to depreciation, government social insurance, private pension, and medical insurance systems are far from perfect, leaving elderly people no choice but to rely on remittances from adult children. At the same time, most children voluntarily shoulder the responsibility to support their aged parents, especially those in poverty, those who suffer from an illness or those without spouses.

Offspring can offer their parents remittances and daily help as well. They do so just because they care about the wellbeing of their parents. Social and economic development will improve the welfare system, decreasing economic incentive to bring up children. As a result, the birth rate will fall, and parents will rely less on their children.

Exchange hypothesis

Compared with selfless altruism, exchange relationships seek a return in some form, possibly at a later time. The higher the parents’ income is, the more transfer they get from their children, revealing the motivation of the exchange. The motivation can be further categorized according to the terms of the exchange.

There is an internal family debt market because youth can hardly lend money in the capital market, so parents pay for their education as an investment in human resources. In return, the youth provide their parents with material aid when they grow up.

Another category of motivation indicates that the purpose of remittances is an exchange of services. If parents want to transfer in exchange for children’s services and they have inelastic demand, they tend to transfer more to the children who have higher income out of an exchange motivation, while they transfer less driven by altruism. In addition, adult children who offer economic aid and daily care may hope their parents will look after their own children in return.

According to an inheritance exchange hypothesis, frequent visits and contact reflect children’s motivation to be their parents’ heirs. Conversely, parents use their own resources to manipulate behaviors of their children. For example, they might promise that they will leave the largest inheritance to the most filial child.

Based on the indirect exchange hypothesis, those in the middle generation, i.e. those with retired parents and school-aged children, care about and provide economic aid to their parents in order to educate their own children. Education is achieved in daily, frequent and visible behaviors. They hope to receive the same treatment, more frequent visits and more economic aid when they grow old.

Conclusion

Since few parents in China transfer money to their children, this article mainly focuses on research about children’s motivations when transferring money and caring for their parents.

Conclusions are made based on the CHARLS’s outcomes concerning the motivations of intergenerational remittances in Chinese families. Remittances between blood relations are complicated, with various motivations overlapping and influencing each other. The motivations children have when sending money are diverse. Some may have a selfless desire to help their parents while others want to pay their parents back for their sacrifices and investment, or they may want to educate their children by setting a good example.

The tests on the motivations mentioned above found that compared with the Western countries, Chinese children are more likely driven by altruism and give more support to their socially vulnerable parents. People who have lost a spouse, are in bad health or live in poverty are more likely to receive remittances from their children. Parents in bad health or in their late years are more likely to receive economic support, while those without a spouse or home are mostly cared for directly by their children.

At the same time, the data also indicate an indirect exchange motivation. Individuals will visit more frequently and offer more financial aid to their parents to set an example for their offspring in the hope that they can live with and get more financial support from their own children when they grow old.

In conclusion, the traditions of filial piety still encourage close to half of the population to shoulder the responsibility of supporting parents. More vulnerable parents will receive more income transfers depending on their children’s financial conditions. Weathier children offer more income transfers and visit more frequently.

In such an atmosphere, the Chinese pension system faces less pressure than systems in Western countries. However, supporting the growing aging population will be harder for Chinese people due to a lower birth rate. The “crowding out” of traditional modes of elder care needs to be forestalled while the government improves pension and other social welfare insurance systems.

Liu Yan is from the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University.