Big history aims to convey more than the human story

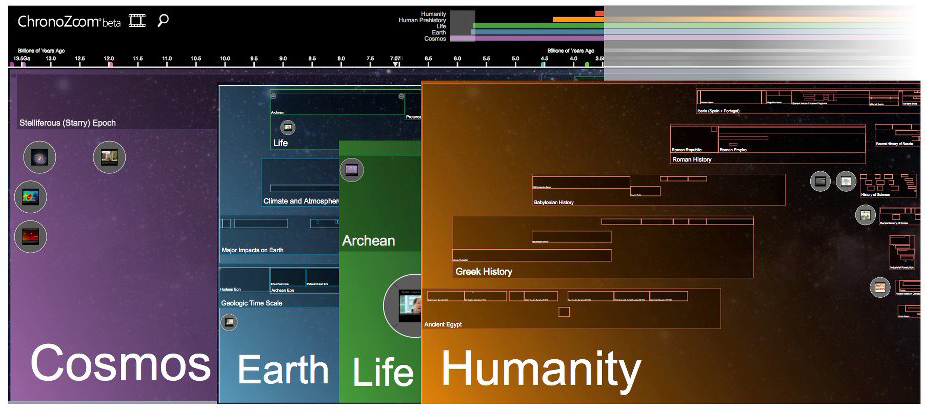

ChronoZoom is a free open source project that helps readers visualize time at all scales from the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago to the present. See more at http://eps.berkeley.edu/~saekow/chronozoom/.

Big history is an increasingly popular paradigm for understanding the past. First formulated by American historian David Christian in 1991, the concept expands the scope of historical research to include events extending all the way back to the creation of the universe while achieving disciplinary synergy with science and the humanities. It integrates studies of the cosmos, the Earth, life and humanity in the context of the bigger picture.

Origin

Big history is rooted in the scientific achievements of the 20th century. Mankind’s understanding of space and time was radically altered by major discoveries such as the Big Bang theory, plate tectonics, carbon-14 dating and DNA, which have been widely applied in physics, geology, archaeology, paleontology and other disciplines. But the rise of complexity science was particularly crucial to big history.

Complexity science studies a wide range of systems to discover how they behave in order to elevate humanity’s ability to understand, explore and reform the world. Scientists can adopt various new technologies and methods to simulate the pre-historical status of the Earth, or even the cosmos. It was natural scientists rather than historians who pioneered research on prehistory. Drawing on methodologies of historians, geologists, paleontologists and astronomers, complexity science has built an unprecedented macro-history based on the latest findings of natural science.

After World War II, countries became closer to one another through globalization. At the same time, historians began to adopt an increasingly global perspective. No longer limited by the constraints of nationality or region, they even expanded the human narrative to include outer space.

In addition, environmental issues in the postwar era also led to the birth of big history. People started to reflect on the toll economic development that had taken on the environment and began to advocate harmony between man and nature, paving the way for the concept of big history.

Formation

The 20th century brought with it rapid scientific development and growing cooperation among disciplines. In his 1920 book The Outline of History, Herbert George Wells started with the formation of the Earth and based his work on the research achievement of various disciplines. Though Wells was not considered a serious historian, the book still made an early attempt to adopt the big history narrative.

In the third technological revolution, interdisciplinary research reached a new stage. Austrian-born American astrophysicist Erich Jantsch released his book The Self-Organizing Universe: Scientific and Human Implications of the Emerging Paradigm of Evolution in 1980. The book deals with self-organization as a unifying evolutionary paradigm that incorporates cosmology, biology, sociology, psychology and consciousness. Though Wells and Jantsch did not use the term “big history,” they spearheaded the way for the narrative.

The term has gained currency among historians since it was first coined more than two decades ago. Christian draws on paleontologist Stephen Gould’s punctuated equilibrium, which holds that everything in the cosmos stays stable in a balanced system, but the system periodically undergoes a significant evolutionary change that breaks the old model of balance and produces a new one. The Dutch scholar Fred Spier elaborated on the system. His research domain shifted from biochemistry and genetic engineering to cultural anthropology and social history. In his 1996 book The Structure of Big History: From the Big Bang until Today, he draws on Jantsch’s theory, using the term “regime” to refer to the formation of big history.

Spier argues that the “regime” has a somewhat regular pattern but will evolve into an unstable model. In this way, he illustrates the complexities of anthropology, nature and other phenomena while exploring the relationships among them.

Development

American astrophysicist Eric Chaisson is an expert on complexity and energy flow, the two major concepts of “big history.” He argues that flow of energy will create complexity, and the increase of energy rate density among a whole host of complex systems gives rise to complexity. Therefore, big history explains the waxing and waning of complexity.

Chaisson divides the time span, ranging from 1.4 million years ago until the present day, into three evolutional periods concerning physics, biology and culture. He further divides these three periods into seven stages: molecule, nebula, star, planet, chemistry, biology and culture.

However, a flow of energy is not sufficient on its own to create complexity. The process requires other conditions.

Already widely discussed in theoretical research, big history is starting to catch on in classrooms as well. To be done properly, any course on the subject requires coordination among different disciplines so that astrophysicists and astronomers lecture on cosmology and the formation of the solar system while geologists illustrate the evolution of the Earth and its structure. Then, paleontologists explain biological evolution, archaeologists and anthropologists elaborate on the origin and evolution of human, and historians explain human civilization and social development. At last, the course will come to an end by looking at the future.

Since the 1980s, big history or something similar has been taught in universities, such as Harvard University, Macquarie University, and University of Amsterdam. The number of graduate projects focusing on big history has been growing steadily, and now hundreds of researchers in universities and institutes are engaged in teaching and research on the subject. At the same time, more than 80 secondary schools in America and Australia have included big history in their curricula. In China, the School of History at Renmin University teaches big history, and it has also introduced foreign web-based lectures through cooperation with YouTube.

Academic exchanges on big history are increasing as more scholars engage in the domain. At the same time, research has gradually extended beyond Western academia. Russia held an international conference on big history in 2005. In China, the paradigm was also discussed at the 20th Annual World History Association Conference in Capital Normal University in 2011.

The International Big History Association was founded in 2010. It serves as a major platform for exchanges among scholars. Its first conference in the US state of Michigan in 2012 gathered more than 100 scholars from the United States, Australia, Holland, the United Kingdom, China and India. At present, the association has more than 300 members.

Characteristics

As an emerging branch of historical studies, big history has distinctive characteristics. In terms of theory, big history examines the past using numerous time scales, whereas conventional history courses usually begin with the introduction of farming and civilization or with the beginning of written records. It mainly explores patterns of the cosmos and other theories from an overarching perspective, while conventional history focuses more on detailed issues like kingdoms, civilizations or wars.

Also, the subject of big history is the cosmos. Its courses generally do not focus on humans until more than halfway through. Conventional history focuses on human civilization with mankind at the center. Big history draws on the latest findings from astronomy, geology, archaeology, anthropology, biology, history and environmental studies. Findings of psychology and philosophy also enrich research on big history.

Big history also has differences in terms of methodologies and dissimilation. It tends to go rapidly through detailed historical eras and draws on the latest findings of various disciplines. Conventional history seeks historical details and accurate evidence from archives. People involved in big history come from various fields. Some of them are not engaged in academic research. In addition, big history tends to be taught more with interactive videos and websites rather than textbooks. Therefore, it has a closer relationship with media.

Though big history is promising, the paradigm is not without its flaws. In such a broad context, it is hard to balance research findings on various space and time scales. Also, it covers too many disciplines for research to be genuinely systematic, making its categorization difficult. However, the point of big history is to break limitations of perspectives and disciplines. It treats all human civilizations as a whole and studies them in the context of cosmic history. All of these reflect globalization and scientific progress—the hallmarks of this era.

Song Yunwei is an associate history professor at Renmin University of China.