Scholars debate merits of ‘folk scientists’

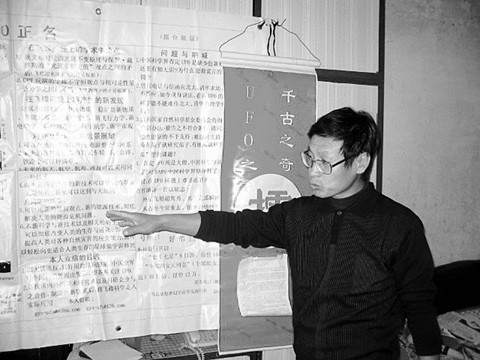

Guo Yingsen, a laid-off Chinese plumber from Fushun, Liaoning Province, explains his theory of UFOs at the gate of a university in Beijing. Guo claimed he could theoretically prove the existence of UFOs and intended to challenge the physics professors of the university.

Recently, scientists observed the effect of gravitational waves for the first time, confirming a theory put forth by Albert Einstein a century ago. In 2011, when the concept was still purely theoretical, a laid-off Chinese plumber with a middle school education named Guo Yingsen argued for the existence of gravitational waves on a popular TV program called Only You.

Though Guo may lack formal academic training, he is still entitled to give an opinion on scientific questions, and he is far from an only amateur science enthusiast in China. Within the scientific community, there is a fierce debate about the role these so-called folk scientists play in the advancement of human knowledge.

Outside of academia, folk scientists have produced many fanciful theories on topics ranging from perpetual motion machines to proofs of Goldbach’s conjecture.

Tian Song, a professor from the School of Philosophy and Sociology at Beijing Normal University, defines folk scientists as “a special crowd doing scientific research away from the academic community, aiming either to resolve a significant scientific question or to overthrow a renowned scientific theory and build a larger system. However, they do not accept or operate according to the basic procedures of the scientific community. As a whole, their work is of no scientific value,” Tian said.

Yin Jie, a professor from Shanxi University, said that the findings of folk scientists are generally rejected because they come from outside of the scientific establishment, which places a high premium on formal training. Since the mid-20th century, the organizational form of science has grown in scale, creating a more professional culture, Yin said, adding that participants in a particular field of scientific inquiry must receive corresponding academic training or they cannot be recognized or accepted by the scientific community.

Respect for academic norms is essential because any research must be conducted on the basis of previous studies, said Ye Liguo, an associate professor from the School of Philosophy at China University of Petroleum. However, “folk scientists are not familiar with academic norms and previous studies, so they can hardly produce creative outcomes,” Ye said.

Despite the skepticism of some in the scientific community, there is sympathy and support for folk scientists. Chen Peng, a young scholar from the School of Technological Science at Beijing Language and Culture University, said that science is free. Anyone who has an interest in and devotion to scientific research is worthy of being called a scientific researcher, Chen said.

But in recent years, some claims put forward by folk scientists have been exposed as pseudoscience. “They are generally a patchwork of scientific terms lacking any originality,” said Zheng Yongchun, an associate research fellow from the National Astronomical Observatory under the Chinese Academy of Sciences. There is a gulf between the passion of folk scientists and their actual research abilities, Zheng said.

Zheng said the boundary between science and pseudoscience is clearly defined according to the method used to reach conclusions. “Science is a reasonable observation that is obtained by logic, inference and deduction. Science is based on phenomena and data,” Zheng said. “The main difference between folk science and science is whether the problem is solved by a scientific attitude and scientific method.”

In theoretical research, a theory’s premises and hypotheses must be illustrated and a conclusion is drawn through inference and deduction, Zheng said. “Furthermore, only when the conclusion’s validity is examined in practice through experimentation, can the conclusion be widely accepted. However, in folk science, they usually just list some scientific terms that they don’t entirely understand, and there is not any specific experimental data,” Zheng said.

Folk scientists not only lack the scientific spirit to seek truth but also lack the scientific method needed to verify findings through logic, Zheng said, arguing that the “scientific research” done by this method will not make any contribution to the progress of human civilization.

Yin suggested that more public lectures on scientific subjects be held. In particular, the distinction between science and pseudoscience should be clarified. At the same time, scholars should have the courage to explain their attitude toward folk scientists and other social issues, helping the public to gain a deeper understanding of real science.

Zhang Qingli is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.