Ethics: a missing aspect in climate change debate

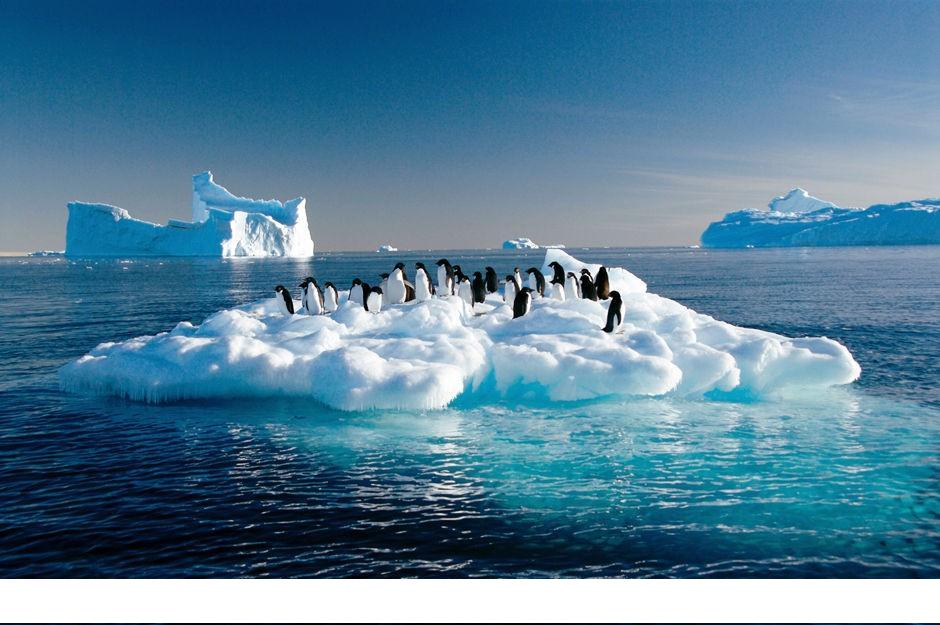

Penguin decline in Antarctica due to climate warming

As the 44th World Earth Day was approaching this year, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon was one of many to propound the need for humankind to take positive action in addressing climate change and other looming environmental threats. Among those voicing their concerns, MIT Technology Review Editor David Rotman encouraged a general reframing of the debate: climate change is not merely a problem for science, he maintained in a review article for his own publication; rather, it poses ethical problems with regard to its impact on different populations and future generations. Apart from scientists and economists, he urged ethicists to play an active role in combating climate change.

The effects of climate change are not something a country can neglect or opt out of, said Li Kaisheng, associate research fellow from the Institute of International Relations at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. Li noted that many issues surrounding climate change are conflated by different cultural understandings of the relation between man and nature, the allocation of rights and obligations between people, etc.

Donald A. Brown, scholar in residence at Widener University’s School of Law, explained that climate change poses multi-tiered considerations of moral obligation: individual agents and states both have responsibility; those who have historically been larger contributors to climate change have a responsibility; and developed and developing countries have respectively levels of responsibility. Brown is the author of the book Climate Change Ethics: Navigating the Perfect Moral Storm, and was also an attendee at the UN Doha Conference where he led a side panel.

Pan Jiahua, director of the Institute for Urban and Environmental Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, voiced concerns that a higher level of urbanization and high-quality consumption are needed for China to achieve its goal of constructing a moderately prosperous society by 2020. Pan voiced concerns about current lifestyles and modes of production in China, which he explained are perpetuating a degree of environmental exploitation that poses a long run threat to ecological security. Ecological security is ultimately the foundation for socioeconomic development; to construct a beautiful China, we have to adjust our consumption pattern and reduce our ecological footprints, he stressed. Stephen M. Gardiner, a philosophy professor at the University of Washington and author of the book A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change, observed that human beings tend to attach too much importance to short-term economic benefits when thinking about climate change policy, both in terms of avoiding making hard decisions, and also in only making environmentally sound decisions if they have an immediate payoff. He argues that we need to establish a more balanced view of the relation between benefit and morality. For example, when addressing this global issue we need to think more about our own responsibilities rather than “pass them on to others,” and we need to consider future generations instead of impatiently seeking short-term gain.

These scholars’ opinions all reflect a general consensus that morality is indispensable in addressing climate change. “As a starting point, scholars are supposed to proceed from the common interest of all humankind, giving greater weight to the requirements of human beings’ fundamental values,” commented Cai Tuo, director of the Research Institute of Globalization and Global Issues at China University of Political Science and Law. “They should articulate an academic vision based on ethics.”

Among the disciplines within social sciences, economics was one of the earliest to seriously explore the effects of climate change and potential solutions, as economists conducted cost-benefit analysis of both. In his 700-page report “The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change” released in 2006, British economist Nicholas Stern provided detailed analysis of the impact of climate change on the economy, society and the environment. He warned that the influence of the perpetually increasing green-house effect on the global economy will be no less severe than that of the world wars or the Great Depression.

We ought to consider the environment as providing a habitat for humanity, but instead we have given undue emphasis to the environment as providing resources, commented Wang Xiaoyi, director of the department of rural and industrial sociology at the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. When the environment is regarded as simply a reserve of natural resources, capital likewise becomes a tool for utilizing these resources, Wang explained, elaborating that the government, especially the central government, will weigh the pros and cons when considering excavating resources, while for-profit business will attach more importance to benefits of excavation. In so doing, for-profit organizations disregard the local population’s dependence on their environment, he added. Wang concluded that when resources are measured merely by the economic benefits provided by their utilization, the environment’s diverse potential functions will inevitably be neglected, bringing about ecological problems.

Clive Hamilton, a professor of public ethics from the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at Charles Sturt University in Canberra, Australia observed that while some consensus on battling climate change has been achieved through international cooperation, states are slow to take action as soon as further measures are perceived as a threat to their own interests.

This one-sided thinking has been pointed out by other commentators. Gardiner talked about the tendency of some economic analyses to “assume that whatever climate damages befall us can be offset by increased economic growth, as if the economy itself is very resilient against climate damages.”

While various measures have been taken against global warming, they have apparently failed to curb it. Numerous ethicists have condemned our current practices as immoral, stipulating that they violate a principle of “intergenerational equity”: if we fail to take responsibility for our own lifestyles and habits, future generations will suffer from our actions.

Speaking on the role ethics could play in addressing climate change, Li Kaisheng affirmed: “It will be a pioneer in advocating right concepts. Ethics can help us frame the debate in such a way that more nations and more people realize the necessity of attaching equal importance to both privileges and obligations when it comes to global issues. If the concepts of fairness and justice can gain more traction in the international discussion and ideational vocabulary surrounding climate change, then we can promote a more cooperative environment around the issue—one in which we can construct a more justified and feasible framework acceptable to all parties.”

John Broome, White's Professor of Moral Philosophy at Oxford, has asserted that ethics can help with right decision-making and that “economics has always to be based on ethical foundations.”

Seconding this view, Gardiner contended that as it is committed to clarifying the essence of and the various moral dimensions embodied within a problem, ethics can help people understand what hides behind a problem. When it comes to addressing climate change, ethics can make people better aware of their responsibilities and duties, he explained.

Given the significance of ethical issues in combating climate change, scholars suggested that ethicists and economists learn from each other. Ethicists can enrich their research by learning from cost-benefit analysis, while economists can take ethics into consideration when determining a discount rate (the rate by which economists discount the value of an investment today based on anticipated future payoff—a higher discount rate equals a lower payoff) for such complex questions as the benefits of investments to mitigate the effects of or prevent climate change. Gardiner suggested that this practice implicitly hazards a moral argument, but often takes it too lightly, resulting in a shortsighted analysis.

Hamilton affirmed that one of scholars’ responsibilities is always “to contribute to human betterment”. He urged scholars to think carefully about what they can contribute to solving the problem of climate change.

Brown voiced similar ideas, asserting that social scientists and ethicists should both play a critical role in policy formation, helping “citizens and students understand the ethical issues that are often hidden in economic analysis.”

Yang Min is a reporter from Chinese Social Sciences Today.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 444, Apr 26.

Chinese link:

http://www.csstoday.net/Item/69326.aspx

Translated by Jiang Hong