Alexievich wins Nobel Prize for works on war, ecology

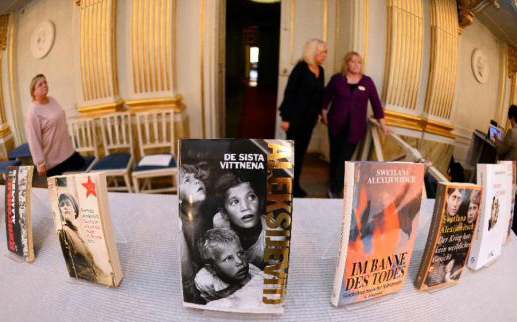

Books by Svetlana Alexievich on display at the Swedish Academy in Stockholm on Oct. 8

The Swedish Academy announced on Oct. 8 that the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Svetlana Alexievich “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

Documentary writing tradition

Born in the Ukrainian town of Ivano-Frankivsk, Alexievich has a Belarusian father and a Ukrainian mother. After graduating from the Department of Journalism at Belarusian State University, she worked as a reporter for many years. Starting in 2000, she moved from city to city for more than a decade, including stays in Berlin and Paris, before settling down in Minsk.

Before winning the prize, she had already made a name for herself in Russian and Western literature. Her main works include War’s Unwomanly Face (1985), The Last Witnesses: The Book of UnChildlike Stories (1985), Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War (1989), Enchanted with Death (1993), Chernobyl Prayer: Chronicles of the Future (1997), Secondhand Time (2013). Translated into several foreign languages, her works have won many awards, including the Swedish PEN in 1996, the Leipziger Book Prize on European Understanding in 1998, the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2005 and the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 2013.

For Chinese, Alexievich is a “familiar stranger.” Those familiar with her are mostly readers with an affinity for or professionals who specialize in Russian literature. As early as the Soviet period, her name had become part of Soviet literary history. The general public’s lack of familiarity with her can be attributed to the relatively small size of her body of work and the relative unattractiveness of her chosen genre compared to novels, poetry and prose.

In terms of writing style, Alexievich’s works draw upon the documentary writing tradition of Russian literature. Her works are the combination of the “virtual” and the “actual.” There are few character arcs of protagonists that runs through the whole story or soul-stirring plot lines. In her works, Alexievich uses lots of oral documents. Over the course of many years, she obtained the writing materials through interviewing her subjects. It is those non-fiction materials that make her works “real.”

Her writing style is rooted in the documentary literature published during World War II. Alexievich considered Soviet writer Ales Adamovich to be her role model and mentor. Collaborating with other writers, Adamovich finished the famous documentary works Out of the Fire (1974) and The Blockade Book (1977—1981). Carrying around a sound recorder, they visited several hundred survivors, victims and witnesses of World War II. They completed the writings according to interview-based transcripts and diaries.

This style of writing can be traced back to a book published in the mid-1950s called Heroes of Brest Fortress by Sergei Smirnov. The book is a collection of the taped conversations, letters and other materials accumulated by the author since 1954 when he began his visits and interviews. It was the book that started the trend of using a large number of oral sources.

Recorder of war history

Not only did Alexievich inherit her style from Russian documentary literature, but she also carries on the tradition thematically. What is revealed in her plain and unadorned language is profound anti-war themes as well as a reflection on the havoc that calamities wreak on mankind and the environment. She examines the effects that the changes of the era and society have had on the internal world of common people.

The stories in War’s Unwomanly Face and The Last Witnesses were created using World War II, which occurred more than 70 years ago, as the background.

During that war, Soviet women, together with their male compatriots, entered the battlefield. Not only did they take on jobs as the doctors, nurses and telephone operators on the front line but also served in combat as infantry and snipers. Before the creation of the two books, the suffering of Soviet women on battlefields was rarely a focus of Russian-language war literature.

The reason for this can be found in a quote from the writer Ivan Kondratiev, whose representative work is Saltychikha: “I have long since come to realize that I am obliged to shoulder the responsibility for our female comrades-in-arms—such responsibility is mine as a writer and also an individual being. Long ago, I began to write about them. However, now I find myself absolutely unable to create real works about females because I did not know about all that affected them until I read the book War’s Unwomanly Face.” Unlike the grand scenes of war and the heroic ambition portrayed by male writers, the works of Kondratiev, with female soldiers in the frontier as the protagonists, evince the unique sentiments and feelings that females have toward life. Allowing women to tell stories about themselves or their compatriots, Alexievich seeks to reveal the cruelty and mercilessness of the wars waged by fascists.

The Last Witnesses offers a view of World War II through the eyes of more than a hundred children who experienced it. The book documents the misfortune that the wars among adults cause to family members and ordinary people. The two most vulnerable groups of the war—women and children—are afflicted with dual harm both psychologically and mentally—such perspectives endow Alexievich’s works with strong anti-war sentiments that are rare in the works of other writers.

War’s Unwomanly Face and The Last Witnesses constitute an important part of the world anti-fascist literature. They enrich Russian works on war, the landscape of which has traditionally been depicted by male writers. Zinky Boys, Alexievich’s other major book, records the memoirs from the Soviet soldiers who survived the Afghanistan War and the relatives of those who died. The work draws attention to the way wars affect human life and nature.

Writing about ecological crisis

After tackling the subject of war, Alexievich expanded her vision to include humanity’s spiritual crisis caused by ecological disasters and social instability.

She looks back on major events some time after they took place and reflects upon the meanings behind them. Similar to her works on war, Chernobyl Prayer was also created several years after the catastrophic nuclear accident at Chernobyl happened.

As early as when she wrote War’s Unwomanly Face, Alexievich had expressed her concern about the threats technology poses to humans and the environment as a whole. She wrote, “Living in an era of highly improved science and technology, we are threatened by not only the real wars that humans experience but also the wars of ecological disasters.” In Zinky Boys, she further expressed her philosophy on nature: “For more than once, I keep thinking that birds and fishes, similar with other living things, have the right to form their own histories. I believe there will be a day in the future when their histories are written by someone.”

Chernobyl Prayer features stories of life in a region polluted by a nuclear meltdown. It portrays startling and dreadful phenomena that underscore the great hazards humans and the entire ecosystem face. It also documents the hideous deeds of governments, including covering up the truth and suppressing the freedom of expression. Chronicles of the Future, the subtitle of the book, could be seen as a thought-provoking prediction that similar ecological catastrophe could happen again. Alexievich’s foresight was validated years after the book was published when a nuclear disaster strucked Fukushima, Japan.

Kong Xiawei is from the Institute of Foreign Literature at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.