Chinese zodiac relies on concept of totem worship

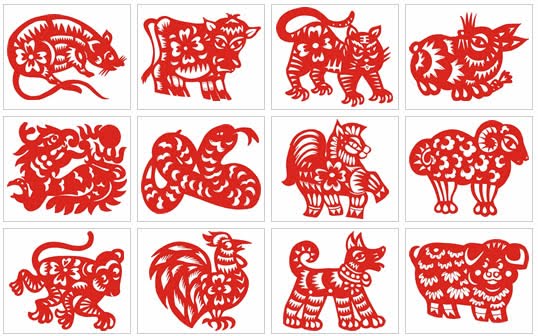

The Chinese zodiac is a 12-year cycle that relates each year to an animal. It begins with the sign of the rat, followed by an ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and pig.

As a significant part of Chinese traditional culture, the Chinese zodiac is quite familiar to Chinese people. The Chinese zodiac is a dating method combining 12 animal signs and 12 earthly branches. But tracing the origin of this zodiac is difficult.

The word “totem” stems from the transliteration of the Ojibwa dialect in the Algonquin clans of North American Indians. The word comes in a number of variations in English, such as “totam,” “dodaim” and many other spellings, until the spelling “totem” was finally confirmed which holds the connotation “his kinship” in the Ojibwa dialect. The first person to introduce the word totem to Western academia was John Long, a British East India Company translator and merchant. He lived in North America for many years and became intimate with North American Indian customs. He published a book now titled Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader Describing the Manners and Customs of the North American Indians 1791. This was the first time the concept of “totem” was outlined for Western readers. Half a century later, British traveler George Grey published Explorations in Northwestern and Western Australia in 1841, which contained many descriptions about native Australians who maintained totems. Since then, the term “totem” has been gradually accepted by academia and is widely utilized, with many derivative academic concepts, such as totem culture, totemism and totem worship.

Totem worship is one of the most important stages of a primitive society. Limited by knowledge and imagination, humans in primitive societies regarded everything in the world, including animals and plants, with reverence. Totems at that time were based on many concrete forms. Some were animals, plants and natural objects or a simple combination among them. Whether or not they take the form of concrete objects is a primary criterion for assessing totems that are part of totem culture, which is also a major characteristic of totem worship.

Totem worship is an outcome of animal worship and ancestor worship. In collections of ethnographic materials, animal totems hold an important place. This was closely related to humans’ long-term survival in the age of hunting and animal husbandry.

Yan Fu (1854-1921), a distinguished scholar and translator in the late Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), was the first to introduce the word totem to China. In 1903, he translated British scholar Edward Jens’ A History of Politics into Chinese and brought the word totem to Chinese academia.

With further research, multiple pieces of evidence have emerged indicating that ancient Chinese worshiped snake totems, as shown in ancient books and materials of physical anthropology. Besides snake totems, there are numerous examples of other animal totems. The book The Classic of Mountains and Seas, which was accomplished around the pre-Qin period (before 221 BC) and the early Han Dynasty (206 BC-220), recorded a large number of mythologies and legends. By reading these mythological stories, we can trace out the signs of animal worship or totem worship left at that time.

Ever since the Shun period (2097-2037 BC), China has adopted 10 heavenly stems in combination with 12 earthly branches to designate years, months, days and hours in the lunar calendar. The use of animals as a dating method has been traced back to ancient nomadic tribes in northwestern China. By the Qing Dynasty, scholars had realized that ancient northern nomadic Chinese connected the dating method of animals with the Chinese zodiac and concluded that the Chinese zodiac stems from a dating method that utilized animals. On this basis, the birth of Chinese zodiac relied on the popularity of animal worship and totem worship and the application of the dating method of heavenly stems and earthly branches. Both supplement each other, and neither can be omitted in studies of this concept.

Di Yongjun is from the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.