Hellenistic-Roman political philosophy posed challenges to ruling classical paradigm

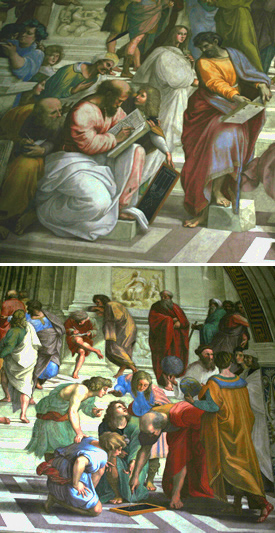

This is a picture by Raphael. Above: Epicurus in a laurel wreath gives a dissertation on pleasure. Below: Euclid teaches geometry, Zoroaster holds the heavenly sphere and Ptolemy, the earthly sphere.

Despite being formed in the ancient world, Hellenistic-Roman philosophy bears many of the characteristics of modern philosophies and there is a lot of originality. In many ways, it challenges the classical paradigm of philosophy.

According to classical political philosophy, the ultimate aim of philosophy is to enlighten individuals who have rational minds and are willing to pursue virtue. But those who are merely trying to guarantee their means of subsistence, on the other hand, are more likely to resort to using the power of the most respected rulers.

This philosophical paradigm holds the intrinsic value of political life in high esteem. It states that although politics is derived directly from the necessity of tackling conflicts of interest, the essential goals of politics go far beyond dealing with the affairs of groups.

When politics develops into its advanced form, its genuine function is to grant human beings a shared life experience of nobility, humanity, fraternity, and justice. The ontological basis of classical political philosophy stresses community—the city-state that commits to the well-being of its citizens. If the individual breaks away from the political community, he may get lost in his own self-identity.

According to the schools of Hellenistic-Roman philosophy, the coercive “natural order” in any vertical line of authority embodied in classical political philosophy, would advocate and demand the individual’s sacrifice and contribution, thus bringing a lot of maladies. Therefore, most Hellenistic-Roman philosophers insisted on reducing the significance of rationality and politics.

First of all, the schools of Hellenistic philosophy all denied that political life is as sophisticated and intrinsically valuable as to constitute the whole of human life. The Epicureans and Stoics both preferred a non-political life with the slogan “living by nature,” thus, most of their representative figures lived in seclusion and solitude. In Stoicism, the only good is that of the inner virtues—even participation in public political life does no more good to those who are previously possessed with inner peace, and the exterior political action or honor is dispensable for one’s living. Stoics believe the “neutral things” that are the objects of a busy political life are worthless; classical politics, which centers on the bravery and indignation of humans, can easily lead to wars and bring about various kinds of brutality and moral decadence under the cover of ethics.

Second, the fact that philosophers of the Hellenistic period valued the inner activities instead of political ones definitely meant that they rejected the conceptual approach of the city-state in the ontological sense. In Epicureanism, the individual himself and his feelings are the most fundamental to human life while other factors play constructive roles to serve individuality. To the philosophers of that period, laws, as means of assuring justice, were made for individuals’ self-protection. To avoid mutual damages and distress inflicted by each other, men entered into social contracts to not hurt each other. This was how justice and law originated. Since then, justice has been stripped down its intrinsic value. Unlike Epicureanism, Stoicism stresses universality and community. For Stoics, all men, assumed to be rational, are citizens of one utopia.

Such thought is indisputably non-political, but why do we still call it political philosophy in definition? Political philosophy differs from politics in that it reexamines politics in terms of ethics and the basic principles of value. The basis of Epicurus’ theory of political ethics is perceptibility, that is, each person’s experience or perception. Epicurus believed happiness and sorrow constitute the root of all values. Such a point of departure would definitely lead to the understanding that the reverence for the value of political action and the awe and worship for deities in classical political philosophy would only make individuals lapse into fear, pain and lack of freedom. Hence, only by acknowledging the vulnerability of man can one strike social agreements that help realize the aversion to harm, wherein penalties can effectively safeguard laws and assure peace for the community.

Shattering the ethical foundation of classical political philosophy, Hellenistic philosophy stirred shock among the public at that time, but only the Epicureans and Stoics were “identified” as the biggest threats and repeatedly criticized. Among the opponents, the most famous were Cicero and Plutarch, who asserted themselves as champions of classical political philosophy.

In counterattacking challenges posed by the newly arisen political philosophy, the opponents of the Hellenistic philosophy tried to expound upon the crucial value of political life and sought to justify the legitimacy of the community. To them, lifestyles vary with different people in terms of superiority or inferiority, thus those who are winners in their lives should pursue a type of higher-valued political life that could make it possible for the virtues exclusive to humans to be brought into full play. In this way, human beings are able to enjoy the happiness brought by those built in human nature, such as fraternity, honor and wisdom. As far as they were concerned, notions of community and justice were prescribed by the sacred natural laws, and each true male ought to possess sublime character. To the opponents, either the egotistical private life of the Epicurus or the value proposition of the Stoics that overlooked the traditions and ethics left the due real responsibility of citizens into oblivion.

Scant in number, the elementary paradigms of political philosophy are characterized by classicality and modernity as the major representatives.

The “modernity” here denotes two aspects: one is sense-and-perception oriented, the core of which is humanism which the Enlightenment and utilitarianism advocate. The tenet of pursuing happiness means the inability to bear brutality or pain. The other is oriented toward dignity and equality, with Kant’s deontological theory as the representative, which is proposed by many contemporary thinkers. If we claim that the philosophical basis of humanism is “compassion” (Adam Smith’s sympathy), according to the deontological theory, the right of equality, which can be demonstrated through rationality, carries more weight than compassion.

Modern Western political philosophy is usually inclined to trace its root back to the Hellenistic-Roman political philosophy. For instance, Kant praised Stoic ethics. And modern thinkers of the deontological theory tend to seek the rationale of equal “dignity” from humans’ rational power, which is exactly what Stoicism stresses—Stoicism, by drawing upon the ethics of classical virtues, argues that all people possess equal “inherent dignity” and everyone is the winner of life, as a result of which, they loathe sympathy or mercy most. Among contemporary scholars that advocate globalization, most of them adopt the notion of neo-Stoicism anew because to them, Stoic philosophy has broken the boundary of city-state and convention in the conceptual sense. However, the increasingly growing neo-naturalism as part of the contemporary political philosophy, by resorting to Epicurus’ ideas of empirical reductionism and happiness, tries to elaborate that morality and politics are both the products of the tacit agreement between individuals. As a result, it rejects pre-conceived morality and the inherent value of humans.

Bao Limin is from the Department of Philosophy at Zhejiang University.