Bamboo slips offer new insight into I Ching history

Liu Dajun

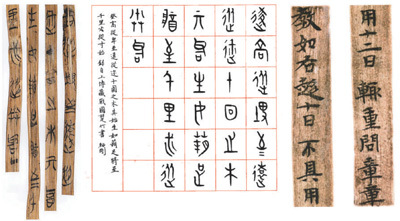

I Ching on Chu bamboo slips from the Warring States period collected by the Shanghai Museum have clearly proven to us that formation and development of early I Ching studies was rich and complicated.

Liu Dajun (1943- ) is a famous expert on the I Ching. He serves as the researcher of China Central Institute for Culture and History, a tenured professor at Shandong University, the president of the Society of Chinese I Ching Studies and founder and editor-in-chief of Studies of I Ching. His representative works include Outline of I Ching.

Although the I Ching, sometimes known as The Book of Changes, is honored as the “foundation of Chinese classics,” it is very difficult for people to read. Serving as a manual for divination, the book has an air of mystery. Recently, a CSST reporter talked with Professor Liu on principles of the I Ching and image-numerology, bamboo slips, and research highlights.

CSST: How do you evaluate the academic and cultural value of the I Ching?

Liu: The I Ching is a remarkable book in the history of Chinese culture. Today academia widely acknowledges that the book was published in the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 BC). But from the view of archeological discoveries and studies on the digits of changeable divination, the formation of symbols of hexagrams and lines in the I Ching has undergone long-term development and evolution, which can be regarded as a footprint left by Chinese thought and cultural development from ancient times.

Just as German philosopher Ernst Cassier once said about human essence: “Humans are not so much ‘social animals’ or ‘rational animals’ as ‘animals of symbol,’ which are animals using symbols to create culture.” He argued that animals can only make a conditioned response to signals but humans can transform signals into symbols with conscious meanings and use these symbols to create culture. As a cultural creation, hexagrams and lines in the I Ching contain a record of Chinese ancestors’ original ideas about heaven, earth and humans. In this sense, although the I Ching was published in the Western Zhou Dynasty, it is rooted in ancestral wisdom and Chinese civilization.

Undoubtedly, the I Ching uses the “image” as a means of ideographical expression and thinking. Similarly, our Chinese characters utilize pictographs, self-explanation, echoism, ideographs, mutual explanation and phonetic loanwords to express meanings, completely distinguished from those of other countries. They are a type of image as well. So to speak, this form of ideographical expression and thinking in images forms the foundation of Chinese culture and paves the path for its development.

CSST: In recent years, a number of bamboo slips on I Ching studies have been excavated and brought to the public’s attention. So what do you think about the significance and academic value of these documents?

Liu: In recent decades, a large number of I Ching studies documents from the pre-Qin period, Qin (221-206 BC) and Han (206 BC-AD 220) dynasties were unearthed and we have had the honor to see these previously undiscovered 2000-year-old documents. Among these documents, there are some fragments about I Ching studies, such as the subject of numeral divination carved on oracle bones or utensils, I Ching hexagrams from Chu bamboo slips in both Baoshan and Geling of Xincai. We have also discovered the three books of “changes,” or Yi, which are ancient divination texts that include Lianshan from the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070-1600 BC), Guicang from the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC) and the I Ching from the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BC). More importantly, we discovered annotated editions of the I Ching from the Warring States period (475-221 BC) and the early Han Dynasty, including Mawangdui silk books, Chu bamboo slips from the Warring States period collected by the Shanghai Museum and Han bamboo slips in Fuyang, Anhui Province. Moreover, an article was published titled “Method of Divination” using the bamboo slips from the Warring States period collected by Tsinghua University, which were recently released. These new I Ching studies documents tremendously expand the academic scope of the current research on annotated I Ching classics as well as the history of I Ching studies to create a new field.

Influenced by a persistent undercurrent of skepticism about the reliability of ancient documents, some scholars regard the I Ching as a record of divination practices only. They consider the study of the I Ching as being useful insofar as it reveals the real meaning of divinatory phraseology in the divining statements. Also, since Notes on the I Ching was discovered, image-numerology and principles that people who study the I Ching follow have all been denied. With new discoveries of archaeological materials, more and more people are starting to realize that the publication and meaning of the I Ching and its relationship with the annotated classics are more complicated than those simple, one-sided arguments proposed by those scholars who just “observe from their own perspectives and believe their observations.” The bamboo slips of I Ching studies represented by annotated classics of the I Ching in Mawangdui silk books and I Ching on Chu bamboo slips in the Warring States period collected by the Shanghai Museum have clearly proven to us that the formation and development of early I Ching studies was rich and complicated.

CSST: At present, the field of I Ching studies has become famous and attracted wide attention from the public. So what’s your view on I Ching studies in the near future?

Liu: We think that for a very long time, I Ching studies will still be a research focus, with the excavation of bamboo slips of I Ching studies. The discovery of different versions of the I Ching, the excavation of bamboo slips of Notes on the I Ching and other relevant documents about divination all provide a valuable reference and an unprecedented opportunity to discuss issues, such as the formation, structure and connotation of the I Ching, academic quality conversion of early I Ching studies, creation and compilation of Notes on the I Ching, the hermeneutic relationship between the connotation of Notes on the I Ching and The Book of Changes, and the influence and function of I Ching studies in the early Han Dynasty on the discipline in later generations, especially classical learning based on earlier texts in the Han Dynasty, which exerted a great influence on classics of the Han Dynasty. Scholars in the field of I Ching studies should take this responsibility and never let this opportunity pass.

Moreover, keeping with the trend of reviving traditional culture, research on the history of I Ching studies, including the intellectual history of I Ching studies, should all return to the position of the history of classical learning, develop comprehensive research on I Ching studies corresponding with the whole picture of classical learning, and explore its abundant academic connotations and ideological implications. Because of the division of modern disciplines, the main body engaging in I Ching studies on the Chinese mainland is professionals in Chinese philosophy, but most I Ching studies scholars and experts in Taiwan work in the Department of Chinese of different universities, which means philosophy casts a shadow over I Ching studies on the Chinese mainland and even the entire discipline. On the one hand, this enables us to better understand the thoughts and evolution of traditional I Ching studies. On the other hand, it covers many valuable research topics in I Ching studies from the perspective of classical learning.

Modern research on the history of I Ching studies should fall under the purview of classical learning, and we should put I Ching studies in the place of traditional classical learning’s academic quality and development. Only in this way can we fully explore the spiritual and cultural meaning of I Ching studies and discover the function of I Ching studies in traditional cultural development instead of only analyzing the concept and evolution of I Ching studies. Under disciplinary classifications that use Western standards, the field of I Ching studies has made researchers feel bored and disabled. The only way to solve this issue is to make I Ching studies return to its essence as a part of the classics. This not only takes into account the original historical context and background of I Ching studies, but it is also an appropriate research perspective that captures the primary spirit of I Ching studies.

Of course, it doesn’t mean that returning to the essence of I Ching studies as a classic is returning to the ancient. This is infeasible and impossible. All responses should be processed within the context of the new times. So there still is a long way to go. We cannot depend on the power of one or two persons. Instead, it needs joint efforts.

Kuang Zhao is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.