Think tanks must balance academic, advisory roles

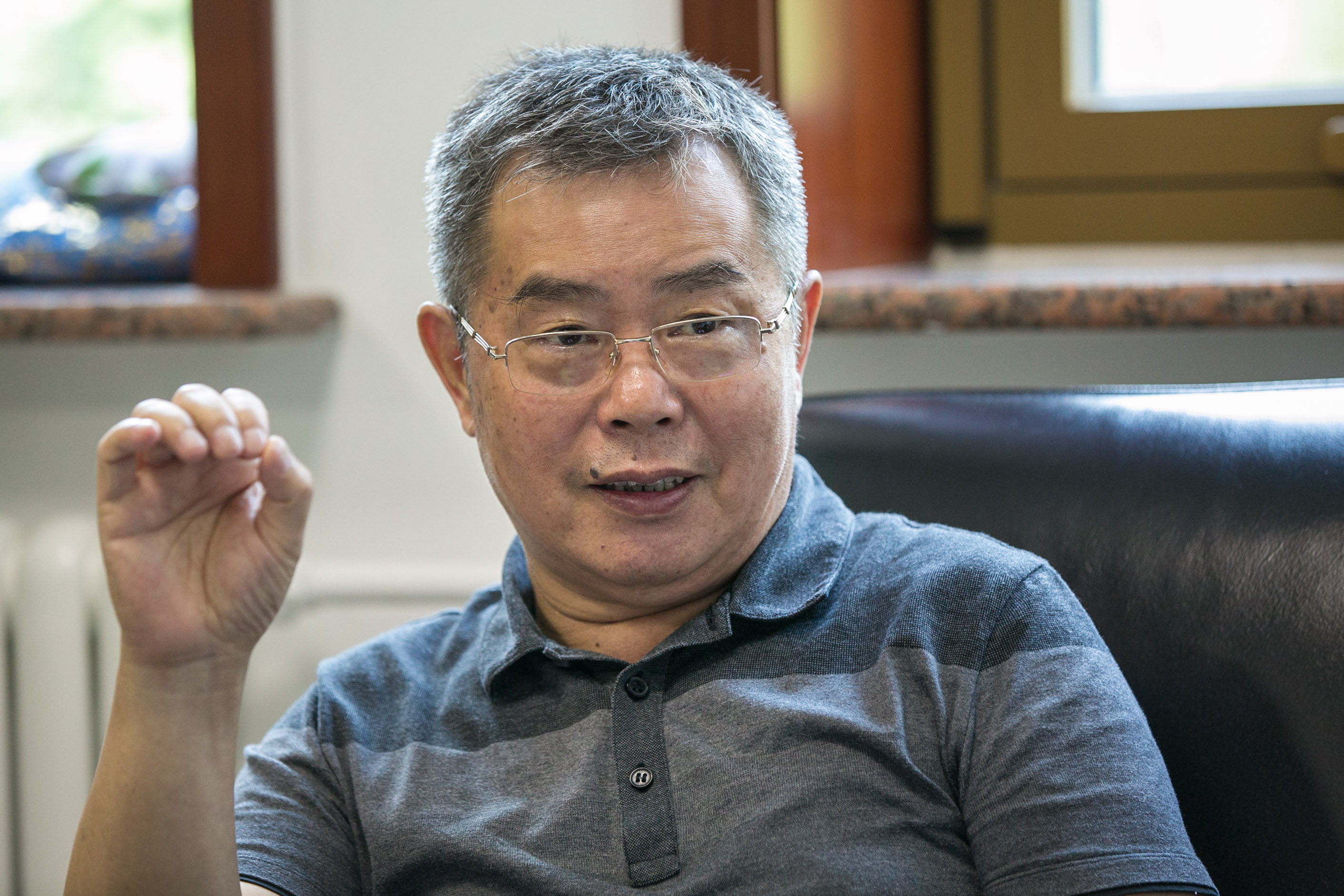

Li Yang, a famous economist and former vice-president of CASS

Office buildings of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), the top think tank in China

Li Yang is former vice-president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and also director of the Academic Division of Economics at CASS. A famous economist, he has earned the “Sun Yefang Economics Prize,” the top economic award in China, four times and published a host of monographs, translations and papers.

As a leader in one of China’s premier think tanks, Li Yang devotes much of his time to considering the relationship between their academic and advisory functions, because CASS, which he serves, is a think tank, brain trust of the State Council, a center for Marxist thought, and the top academic forum for philosophy and social sciences in China.

CSST: There have been doubts whether government-affiliated think tanks can do independent research. What do you think of that?

Li: According to an old Chinese saying, it is the highest honor for civil officials to die for expressing criticism and it is equally honorable for military officials to die on the battlefield. In other words, if a civil official has an opinion that will benefit his country, he will defend it at any cost. Daring to advise the government has been a fine tradition of Chinese scholars and will always be.

In Chinese economics, the “Sun Yefang Economics Prize” is the most important award. As former director of the Institute of Economics at CASS, Sun was the exemplar of an outstanding adviser within the Chinese political system. He even went to jail for defending the truth. Social sciences scholars represented by Sun are excellent role models of Chinese intellectuals.

The high sense of integrity exemplified by Sun and those like him, who are never bent by power or force, can answer your question, proving that official think tanks are able to engage in independent research. Moreover, considering the special role CASS plays, its research achievements might make a major difference in social and economic development.

CSST: Many Chinese research institutions, including CASS, are facing the dilemma of balancing their roles as think tanks and academic institutions. What are the differences between academic research and advising?

Li: In essence, academic research and advising are vastly different in the following five ways.

First, academic research aims to develop theories, opinions and concepts, while advising is about using existing theories, opinions and concepts to interpret practical issues and make policy suggestions to resolve real problems.

Second, the personal interests of scholars guide academic development, while advisory bodies are expected to gather experts of various fields, mobilize all resources and balance opinions of multiple parties to reach a consensus.

Third, academics stress accumulation, while think tanks are required to respond to practical issues in a timely and rapid manner.

Fourth, whether an academic result is good depends on knowledge accumulation and inheritance, while think tank outcomes are judged by their influence on state policy, the attention they receive from related leaders and departments, and the extent to which they affect the public.

Fifth, academic development relies heavily on the method of cultivating scholars, but think tanks place the emphasis on “choosing the right person for the right job.”

CSST: How can these differences be addressed institutionally?

Li: The functions and operating modes of academic institutions and think tanks are so different that proper systems and mechanisms should be installed to strike a balance between the two. Based on other countries’ practices, two institutional arrangements are common around the world for handling the relationship between research institutions and think tanks.

The first is institutional separation. Different institutions assume academic and think tank roles, and no mixing is allowed, which is to say, if an institution is regarded as academic, it should be devoted to doing down-to-earth research. Its achievements should be evaluated with respect to the papers it has published in domestic and foreign academic journals, its leading role in disciplinary development, and its clout in international academic conferences.

A think tank, on the other hand, should dedicate its efforts to strategic design and policy consultation, and it should pay attention to policy impact and its influence on the public. Publishing papers and building disciplines should not be part of its agenda. Take Taiwan, as an example. In Taiwan, the Academia Sinica is set up as an academic forum, while the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research and the Industrial Technology Research Institute are think tanks.

The second is to combine the academic and think tank roles, which are undertaken by exclusive subordinate units, featuring “distinct function, moderate communication and mutual support.” A few world-renowned universities fall into this category. Stanford University, for instance, controls more than 30 research centers, including the globally famed think tank Hoover Institution. The London School of Economics has 26 research centers and institutes, playing an important role in the decision making of the British government. Compared with purely academic institutions and simple think tanks, multi-functional universities have the advantage of a free exchange of researchers among affiliated teaching departments, scientific research institutes and think tanks. First, due to functional division, the assessment mechanism is specialized, hence no inequality is engendered. Second, because of free transfer of personnel, academic research, policy design and teaching can complement and support each other. It is therefore reasonable to divorce academics from think tanks.

At CASS, we have been discussing an issue: Are policy reports research achievements? In a think tank, they are undoubtedly its achievements. But in an academic institution, research achievements are papers published in core journals, and most policy reports are not counted. That is to say, if the academic and think tank roles are integrated within one framework, there should be two separate assessment systems. If the two are separated, different assessment criteria will make positioning clearer.

CSST: In recent years, the University of Pennsylvania has been issuing a global think tank ranking annually. What is your evaluation of the influence of think tanks?

Li: Think tanks gain traction by different means in different countries, so the criteria to evaluate them should be different. When James McGann, who is in charge of the Global Go-To Think Tank Rankings at UPenn, came to China and talked with me, I gave him a brief introduction to the channels through which CASS gives play to its think-tank role. For example, CASS often sends scholars to give lectures to state leaders and submit important reports, which are not disclosed to the outside. Furthermore, our institutes have rather close partnerships with government departments, which is not made known to the public either. However, these are the immediate and major ways CASS functions as a think tank, since it participates directly in policymaking and provides consulting services for policymakers. I told McGann, these are beyond your evaluation criteria, so your rating is not comprehensive.

I don’t think it is wise to care too much about evaluations by outsiders. What matters most is to position ourselves correctly and perform our duties well. It is enough to bear in mind what kind of think tank CASS is, how to perform its think tank role and what an irreplaceable status it enjoys in the state’s decision-making system. We must be soberly aware that we cannot do everything, so we should not do what we are not good at. It is very important to put ourselves in the right position. For a long time, CASS has been committed to offering countermeasures and ideas when involved in rolling out strategies for China’s economic and social development. Through countermeasures, we distinguish ourselves from traditional academic institutions like colleges and universities. With ideas, we are different from policy research divisions of government departments. Our research is comprehensive, well rounded, problem oriented and thoughtful—backed by profound theories yet unaffected by our own interests. In short, CASS should first be good at discovering new problems and then providing countermeasures and ideas, so that it can bring its think tank role into full play and gain a foothold in society.

Ren Zhong and Yang Xue are reporters at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.