Censorial reforms failed to prevent Qing collapse

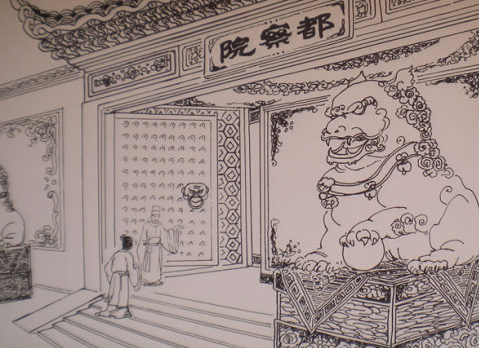

The three Chinese characters on the plaque means “Censorate.” The Censorate played significant surveillance and remonstrance roles for the central government in ancient China.

Each dynasty in Chinese history had a supervisory system to maintain disciplinary surveillance over officials and recommend new policies or changes in old ones. The first exclusive censorial body was founded in the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC).

Supervision of officials peaked in the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) within the Censorate (duchayuan), which served as the “eyes and ears” of the emperor for exposing corruption. Nevertheless the imperial court’s efforts to tighten supervision in response to turmoil toward the end of the dynasty did little to prevent its eventual collapse.

The Censorate was headed by a left censor-in-chief (zuo duyushi), who had left deputy censors-in-chief (zuo fuduyushi). The right censor-in-chief (you duyushi) and right deputy censors-in-chief (you fuduyushi) were subordinates to their left counterparts and held concurrently by local officials, such as the governor-general (zongdu) and grand coordinator (xunfu).

During the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (1723-35), the Six Offices of Scrutiny (liuke) – personnel, revenue, rites, war, justice and works – in charge of monitoring the flow of documents between the throne and the parallel Six Ministries (liubu) were incorporated into the Censorate.

Meanwhile, many investigating censors (jiancha yushi) were appointed to impeach wayward officials and advise the emperor on conduct or policies.

Censorial reforms

Due to high centralization of power in the late Qing Dynasty, the supervisory function of the Censorate weakened significantly.

Following the invasion of the Eight-Nation Alliance, the Qing government was forced to sign the humiliating Boxer Protocol that reduced China to a veritable semi-colony.

In a bid to turn the dire situation around, the Qing court underscored the urgency of carrying out reforms in an imperial edict. In terms of legal reforms, the edict made it explicit to draw upon Western laws and avoid the weakness of Chinese ones.

With legal reform as a point of departure, the central court initiated the so-called “New Deal” aimed at preparatory constitutionalism. The reform of the censorial system was an important matter in the campaign.

Based on the reigning Emperor Guangxu’s (1875-1908) instructions and discussions with other ministers, Grand Minister of State (junji dachen) Yi Kuang readjusted the Censorate in the following major ways.

First, the recruitment of censors was made more stringent. Previously, the Six Ministries recommended censors and candidates were appointed regardless of their performance in the selection examination.

In the wake of reforms, officials from the ministries were charged with recommending righteous, loyal acquaintances to the court. Meanwhile, the number of referrals and recommendation procedures were also clearly laid out. A limit of three referrals was set for each ministry.

Referrals were discouraged from being introduced in routine, general fashion. Those ill-behaved and dishonest should not be recommended. In the event of a “wrong” recommendation, the responsible minister would be subjected to punishment.

After initial recommendation, the candidates were tested in a palace examination and ranked for further recommendation. Censors in the office were evaluated by the Censorate any time.

Second, circuits (dao) were installed in each province. The original 15 circuits within the Censorate were reorganized into 22 ones. For example, the Jiangnan Circuit was divided into Jiangsu and Anhui circuits, while the Huguang Circuit was divided into Hubei and Hunan circuits.

Following the old rule, the Metropolitan Circuit (jingji dao) of the capital was staffed with two chief circuit censors (zhangdao) and two assistant circuit censors (xiedao). Other provinces were supervised by chief circuit censors only.

Given that the Qing Empire originated in Northeast China, the Liaoshen Circuit was instituted and patterned after the Metropolitan Circuit with two chief censors and two assistant censors designated.

Third, the quota of supervising secretaries and circuit censors (kedao) was specified. According to the proclamation of Emperor Guangxu, the Six Offices of Scrutiny were disbanded and the number of supervising secretaries (jishizhong) would increase or decrease based on actual conditions.

Seals for supervising secretaries were cast, and the number was limited to 20. The original 80 supervising secretaries and circuit censors were thus reduced to 64.

Fourth, the numbers of left censors-in-chief and left deputy censors-in-chief were cut. The Censorate was originally staffed with a total of six left censors-in-chief and left deputy censors-in-chief. As a result, the prefix “left” was dropped and only one censor-in-chief (du yushi) and two deputy censors-in-chief were appointed.

Fifth, a research arm was set up and attached to the Censorate. It was responsible for purchasing large quantities of books and newspapers published outside the capital as reference materials for supervising secretaries and censors to facilitate them to perform their duties.

Censorate reaches a crossroads

The Qing court trimmed the censorial system to stabilize the organization and strengthen administrative management. However, during the reform, Qing decision-makers were debating whether to retain or abolish the Censorate. Although the agency ultimately wasn’t dissolved, the debate changed its function.

At the outset of the reform, many objections were raised to reforming the official system and removing the Censorate. There was a view that the Censorate was functionally similar to the Court of Administrative Justice (xingzheng caipan yuan). If the Censorate was to be preserved, it was necessary to clarify the limits of authority for the two bodies. Some officials proposed making the Censorate a transitional agency to the parliament, while others held the decision on abolishing the institution depended on the situation.

Finally, the Qing court maintained: “The Censorate is the ‘eyes and ears’ of the imperial court and is in charge of pointing out political defects and reporting the suffering of the people to the court, so it should be retained and reformed carefully.”

However, debate continued despite the decision to keep the Censorate. After the collapse of the Qing government, the Censorate was no longer the “eyes and ears” of the emperor and gradually broke away from judicial supervision, which led to its dual transition to an exclusive administrative surveillance body and parliament-like institution. As foreign legal systems were introduced and referenced, functions of the Censorate were inherited by new organizations, such as the Prosecutor’s Office (jiancha ting) and the Administrative Court (pingzheng yuan).

Doomed to fall

During supervisory adjustments, a quasi-parliamentary system was established as manifested by the Court for Aid in Governance (zizheng yuan) and provincial Advisory Bureau (ziyi ju). Nonetheless, these organizations failed to perform the function of parliamentary supervision. A parliamentary supervision system never took shape even by the end of the Qing Dynasty.

In ancient China, there was no clear division of labor in the censorial system. The Censorate had multiple functions, such as administrative supervision, judicial inspection, court trial and even public administration. Essentially, it was a behemoth of administrative authority and judicial power.

Censors were divided into surveillance officials and remonstrance officials. The former was in charge of impeaching officials for misconduct, while the latter was responsible for monitoring policymaking.

The late Qing court transformed the Censorate mainly to purify it as a supervisory agency. However, deficiencies of the “New Deal” coupled with the uncontrollable situation prevented the parliament from ever being in session. Although censorial adjustments cleared up administrative and judicial confusion to some extent, they generated little effect.

Clinging to the principle of “centralizing power in the court,” the Qing government was simply prolonging its decaying rule through the “New Deal” with no substantive changes to the autocracy-oriented bureaucratic system. The adjustment efforts failed to bring the supervisory role of the Censorate into play and instead dashed the public’s last hope for the Qing Dynasty, accelerating the fall of the regime.

Jiao Li is from the Department of Research at the Chinese Academy of Governance.