Smart manufacturing to upgrade ‘Made in China’

A middle school student displays bionic, robotic hands he made for a competition. Artificial intelligence is an important part of smart manufacturing, which can facilitate China’s industrial transformation and serve as an alternative means to tackle its looming labor shortage.

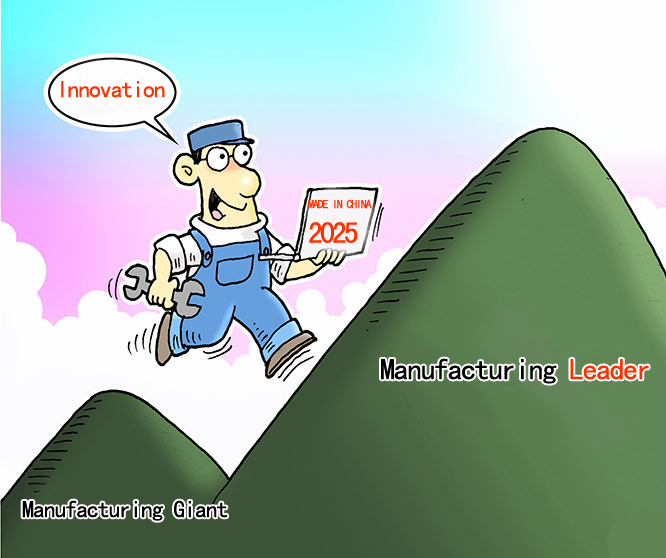

Innovation is the key to transforming China from a manufacturing giant to a manufacturing leader in the world.

Innovation, intelligent transformation and green development are key pillars in China’s new “Industry 4.0” plan, which aims to use smart manufacturing to enable domestic producers to move up the value chain.

After more than 30 years of reform and opening-up, China has cemented its reputation as “the factory of the world.” Nonetheless, the lack of innovative homegrown enterprises has restricted the country from the ranks of global manufacturing leaders.

Externally, the “reindustrialization wave” and challenges from new technologies have also underscored urgency to accelerate the upgrading of manufacturing by integrating information technology into industrialization.

With the accumulation of capital, progress of technology and increase of labor costs, changes in comparative advantage have the potential to pull China out of the low end of global manufacturing.

Stuck at the low end

As economic globalization and engineering techniques advance, international division of labor has penetrated every mode of production. The vertical labor division has gradually replaced the traditional horizontal division as the predominant form.

Most multinationals around the world are in the vertical labor division system. Taking advantage of cheap labor and their own endowments, the majority of developing countries have edged themselves into the global value chain through contracting.

However, this model is incompatible with further industrial upgrading. Developing countries are more likely to be stuck at the low end of the global value chain due to their labor division and overdependence on processing trade.

After reform and opening-up was implemented, China adopted the international labor division system. It held a competitive advantage before approaching its Lewis Turning Point, whereby no more labor was forthcoming from the underdeveloped, or agricultural, sector, and wages began to rise.

Like most developing countries, China is a subordinate in the global value chain because processing trade enterprises are largely engaged in labor-intensive, low-value-added areas.

Multinationals seeking to cling to industrial monopolies have no wish to see China make upgrades or breakthroughs in production, which poses another hurdle to further development of Chinese manufacturing.

Another setback to Chinese manufacturing is the “reshoring initiative” to bring manufacturing back home, which is being led by developed countries at the high end and Southeast Asian countries at the low end.

The long-running contract mode has not only trapped domestic enterprises at the low end, with rising wages and land costs also posing new challenges. Under such circumstances, smart manufacturing is the key to turning the situation around.

Changing comparative advantage

Comparative advantage is a fundamental core concept in international trade. Renowned economist Adam Smith (1723-1790) held that comparative advantage is endogenous and dynamic by nature.

Owing to an inflow of foreign capital and its labor force surplus at the beginning of reform and opening-up, China managed to foster dual comparative advantages in capital and labor within a short period of time. These dual advantages boosted massive processing trade and sped up industrialization.

As comparative advantage changes, the foreign trade model that solely relies on cheap labor gradually lost effectiveness because of internal factors and external competition, along with weakening dual comparative advantages due to diminishing demographic dividends.

In addition to the accumulation of local capital as a result of rapid economic growth, foreign capital has played a lesser role in the Chinese manufacturing sector.

In light of the grim processing trade situation, changes in comparative advantage have generated strong impetus for upgrading the domestic industrial structure.

Currently, the industrial chain of electronics manufacturing has made many breakthroughs in research and development, design, branding and sales. Pronounced manufacturers including Huawei, Lenovo and Xiaomi have achieved huge success, highlighting the importance of integration between manufacturing and the Internet.

Innovation, intelligence springboards

For the Chinese version of “Industry 4.0,” innovation and intelligent transformation are springboards. Eco-friendliness and intelligence represent a breakthrough for the extensive industrial development mode and point the way forward for industry.

To break the low-end deadlock, it is important to first deeply integrate information technology into industrialization and then invest in high-value-added links, such as branding and sales, R&D and design in the smiling curve proposed by Stan Shih, founder of Taiwan-based IT company Acer.

First, it is vital in the Internet age to tap the domestic market and realize the integration of industrialization and information technology.

Although foreign direct investment is motivated by market and cost, with the latter being the main driving force of processing trade, Chinese capital has no mature foreign market for the time being, which highlights the need for greater investment in the domestic market.

Furthermore, the development of information technology is driving the transformation of manufacturing from standardization to individualization, from long to short channels.

It is therefore necessary to build network platforms to support manufacturing entities in hardware facilities and software R&D, keep a foothold on the domestic market and forge an information-oriented manufacturing sector.

Second, more emphasis should be put on upstream design, R&D and downstream sales in the traditional smiling curve. It is urgent to overturn the negative stereotype of “Made in China.” The lack of proprietary brands is the main reason why China is merely a processing plant rather than a veritable factory of the world. In the 21st century, brand competitiveness means having a market edge and distribution advantage in the value chain.

While Chinese capital is expanding, it is necessary to have global perspectives as well as perseverance and resolution for long-term branding to consolidate consumer confidence through green, smart manufacturing and build a corporate image that serves as an industry benchmark. Indeed, branding is an important means of promoting intelligent manufacturing.

Third, R&D and innovation are fundamental to breaking the low-end deadlock. Only when local capital values R&D and innovation can the status of Chinese manufacturing be raised. Although long-term contracting has locked China in its low-end plight, technology spillovers have to some extent helped improve the technical level of Chinese manufacturing.

More importantly, technology spillovers from foreign capital have facilitated cultivation of technical professionals through long-term standardized production.

In view of changing comparative advantage, Chinese material and human capital have been adequate for investment in innovation and R&D in the manufacturing sector. In the information era, consumer demands are able to be fed back to the supply end the first time, allowing innovative ideas to be delivered to the supply end through network platforms the first time.

The integration of industrialization and information technology can provide a good platform for innovation, shortening the R&D cycle and thus making it more cost-effective.

Certainly, R&D and production of innovative products must be supported by strong material and human capital to make real industrial breakthroughs through long-term high-risk investment. Domestic capital must also be continuously invested in talent cultivation, R&D and innovation to build a national innovation system with strong international competitiveness.

Ye Huaibin and Han Chong are from the School of Economics at Renmin University of China.