Top 10 Chinese paintings (VII): A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

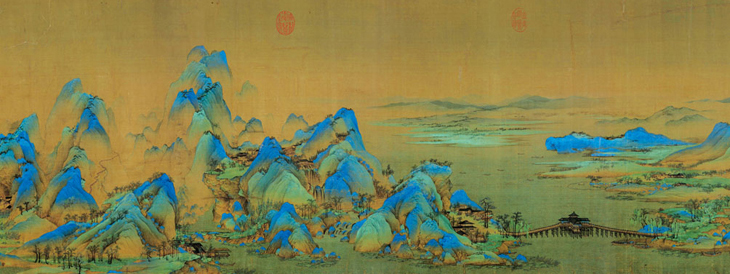

A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains was created by Wang Ximeng (c.1095-?) in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Now housed at the Palace Museum in Beijing, the scroll is about half a meter tall and 12 meters long.

Like most Chinese court painters throughout history, Wang Ximeng left behind few historical records. But fortunately, Cai Jing, a noted minister under the reign of Emperor Huizong (1082-1135) of the Northern Song Dynasty, left an inscription at the end of the scroll of A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains that provided some context for understanding Wang Ximeng and his work.

The inscription wrote that in the third year of Zhenghe (one title of Emperor Huizong’s reign), 1113 according to the solar calendar, Wang Ximeng was 18 years old. If the scroll was definitely created that year, then we can estimate Wang Ximeng was born approximately in 1095.

In A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, we can see that Wang Ximeng’s style was mainly influenced by the blue and green landscape painting technique that General Li Sixun and his son Li Zhaodao innovated in the flourishing period of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Wang Ximeng further built upon their technique to develop his unique style.

There are no records from the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1206-1368) dynasties about what happened to Wang Ximeng after he painted the scroll. But it’s said in the annotation of Song Hui’s Short Commentary on Chinese Paintings in the Qing Dynasty that Wang Ximeng passed away soon after he finished the scroll. Although there’s no evidence to prove whether it’s true or not, few, if any, of Wang Ximeng’s other works survive to this day.

Wang Ximeng’s unique work A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains depicts China’s beautiful rivers and mountains. Surrounded by vast rivers, the ridges and peaks stretch up and down. Because of its precision, gorgeous colors and exquisite strokes, the scroll is regarded as one of the largest and greatest works of the Song Dynasty’s blue and green landscape paintings.

The painter made full use of the multi-point perspective (in contrast to fixed point), the feature of traditional painting scroll, to divide the scroll into six parts. Each part focuses on depicting various mountains, and each of them is connected with bridges or a watercourse. Visually, it makes each part of the landscapes independent and correlative, developing various landscapes with changing viewpoints.

The scroll doesn’t have a faulty stroke and is regarded as a precise and exquisite example of traditional Chinese art. Figures are tiny, but their dynamic status is permanently captured in the picture. Even ripples are drawn stroke by stroke with fishing boats wandering on the water. From the overall perspective, the scroll has a magnificent vigor, and it’s an amazing work whether viewed from afar or from close range.