Academics: Nations can adopt different means to modernize

Gao Xiang, secretary-general of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and editor-in-chief of the Social Sciences in China Press addresses the opening ceremony of the Third Sino-US High-Level Scholarly Forum, held on May 9 and 10 at Guangxi Normal University.

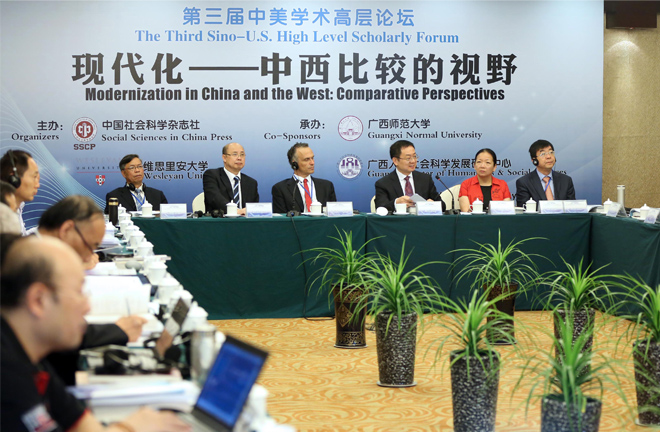

Scholars from China, the US and other countries participate in discussions at the forum.

From May 9 to 10, the Third Sino-US High-Level Scholarly Forum themed “Modernization in China and West: Comparative Perspectives” was convened at Guangxi Normal University (Guilin, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region). More than 30 scholars from China, the US and other areas and regions had intensive discussions on the topic.

Meaning of modernization

Modernization is a complicated issue with more challenges than “tradition” and “enlightenment,” which were the themes for the first two forums respectively, said Gao Xiang, secretary-general of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), and editor-in-chief of the Social Sciences in China Press (SSCP) under the CASS.

“We are still in the historical process of modernization, facing new situations and new problems. Similarly, modernization theories and frameworks are also being tested by new phenomena,” Gao said in his opening remarks.

Gao questioned whether or not the West’s leading position in the process of modernization gives Western countries the right to define modernization and the approaches to achieving it, and if all developing countries must follow the Western model.

Michael Roth, president of Wesleyan University, said modernization needs to be reconsidered in light of the impending global catastrophe caused by ecological crisis and rapid technological progress.

“It seems important for us to reflect on what it means to become more modern—what it means to become a more contemporary or modern society,” Roth said. “We, the US, have finally realized that to become more modern is not to become more American."

In an interdependent society, it is important to encourage progress that serves not only the elites but the people as a whole, he said.

Comparative perspectives

“Scholars shouldn’t be locked in their ‘starting perspectives,’” said Allan Megill, a professor of history at Virginia University. To remain in one place is to diminish the possibilities of new knowledge and understanding, he said.

Attendees provided empirical case studies from comparative aspects. Peter Rutland, a professor of comparative politics at Wesleyan University, introduced a case study on Russia that pointed out post-Soviet leaders face three challenges in trying to modernize their country’s economy—the “oil curse,” “Russian curse” and “Soviet curse.”

Based on Russian experience, he concluded that “modernization is not an automatic process, driven by impersonal, exogenous forces emanating from technological change or the global economy. Agency matters, states do have choices, and leaders can make a difference.”

Zhu Yingui, a professor of history at Fudan University, compared early modernization in China and Japan. He argued that the different functions of the governments in the two countries played the most crucial role.

“Unlike the Meiji government of Japan, the Qing government in China did not make policies and measures embodying state power that worked toward the foundation of capitalist enterprises,” Zhu said.

China’s path

China’s model for modernization stirred robust discussions among participants. Many of them presented articles and speeches pertaining to this subject. While some tried to interpret China’s model, some put the nation’s options for development in a broad historical context. Others emphasized the contribution of China’s practices to modernization theories.

For many developed countries, the process of modernization has already been completed and they have entered “post-modernization.” But for China, modernization is ongoing in people’s everyday lives, said Ma Min, director of the School Administrative Committee at Central China Normal University.

Ma emphasized the “uniqueness” of China’s path to modernization. Because of historical reasons, modernization, industrialization and capitalization in early modern China did not simultaneously occur as they had in the US, Europe and Japan, he argued. The “China Road” and the “China Model” to a great extent are the inexorable outcomes of the development of modern history in China. The fundamental reasons for this are the ways in which China’s traditional history and culture differ from those of the West, he emphasized.

Tang Zhihua, dean of the College of Politics and Public Administration at Guangxi Normal University, described China’s model as “inclusive development” and said traditional Chinese culture forms the foundation.

Modernization is an ongoing process, and modernization theory will be continuously developed, corrected and amended with the exploration of practice, as Gao said in his speech.

The Sino-US High-Level Scholarly Forum takes place every two years. It was jointly initiated in 2011 by the SSCP and Wesleyan University. The next one will be held in the US in 2017.

Feng Daimei is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.