Novel approach sought for promoting Chinese literature

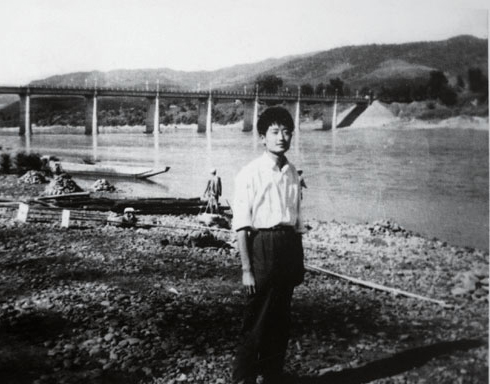

Ah Cheng in 1984, the year The Chess Master was published

On the whole, overseas media and readers have few opportunities to access works of contemporary Chinese literature let alone express opinions about them. In order to devise methods and strategies for promoting Chinese literature to the outside world, this article will use Chinese writer Ah Cheng (real name Zhong Acheng) and his novel The Chess Master, which has been well received in Germany, as a case study for exploring what kind of literary works may be favored by foreign readers and have influence abroad.

The novel is about the life experience of a young intellectual who is sent to a remote farm in the mountains of Yunnan Province to work (people like him were then called sent-down youth). Written from the point of view of an unnamed narrator, readers learn more and more about the titular character, the chess master Wang Yisheng, and what drives him to play Chinese chess.

Chinese traditional writing technique and modern thinking

Although German scholars have praised The Chess Master, it uses no Western writing techniques. Instead, the contrast with and fusion of Chinese traditional writing techniques and modern thinking embedded in it is one reason why it has been successful overseas.

Many of the events that happen to Wang in the novel originate from Chinese folk stories. For example, Wang learns to play chess from an old man who makes a living by gathering garbage to sell and who happens to be a master. There are parallels between this and folk stories that often feature young apprentices learning from masters, and Wang’s victory at a chess competition in the novel is reminiscent of heroes in historical romance.

Although it is enriched by elements of folk legends, modern thinking and concepts are prevalent in the novel. Wang has a lifelong obsession with food and chess. Some German Sinologists regard food as the more important theme because it reflects real material and spiritual hunger of sent-down youth during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Others value the symbolic importance of chess because it represents mankind’s internal power to fight against hunger.

The novel has piqued Western readers’ curiosity about the life philosophy of Chinese people as well as the daily realities of the Cultural Revolution. It opens a path for foreign readers to understand both traditional China and modern China.

Charm of Taoism

The biggest appeal of the novel to overseas readers is its portrayal of Taoist culture. In an era when life was hard and people were lost, those young intellectuals in the novel were still full of vitality in the midst of sorrow and adversity. This optimistic attitude toward life reflects the concept of Wu Wei in Taoism, which literally means “inaction,” but it is better summarized as a paradox: “the action of inaction.” Wu Wei refers to the cultivation of a state of being in which our actions are quite effortlessly in alignment with the ebb and flow of the elemental cycles of the natural world.

In fact, an enthusiasm for Chinese Taoism in German thought emerged after World War I. The Western world often looks to Taoism, especially when there is a spiritual crisis. Starting in the 1980s, Taoism once again came to the forefront as a remedy for spiritual dilemmas in the Western world.

Therefore, what academics in Germany seek in Chinese literature are those elements different from their own culture. Through interpretation of those differences, they can find ways to make up for the deficiencies in their own culture. Chinese culture is an “other” as well as a method. They find a way out of their problems in the process of understanding China. That’s what drives their interest in Chinese literature and Chinese culture.

Unique life experience

The success of the novel is also closely related with the author’s unique life experience. In the criticisms of Helmut Martin (1940-99) and other German Sinologists, they repeatedly mention Ah Cheng’s father Zhong Dianfei (1919-87), a film theorist who was designated as a rightist for criticizing the cinema in his time, and also Ah Cheng’s status as a member of sent-down youth to the countryside in Shaanxi Province, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and Yunnan Province. This shows the methodology of German Sinologists, who aim to understand a writer within the context of the society he or she is in while demonstrating their concern for major historical events that have transpired in China since 1949.

By tracking the typical life experience of Ah Cheng as an intellectual in this tumultuous time period, one can better grasp the social development and major social events of China since the 1950s. The study of Ah Cheng and his literary works enables German Sinologists to better approach China as research subject.

Xie Miao is an associate professor of literature at the Hunan Normal University.