Reviewing transmission of Chinese culture, ideas in early modern Europe

The Portuguese Jesuit Alvaro Semedo (1586-1658) was a missionary in China and his influential History of China was published in multiple languages.

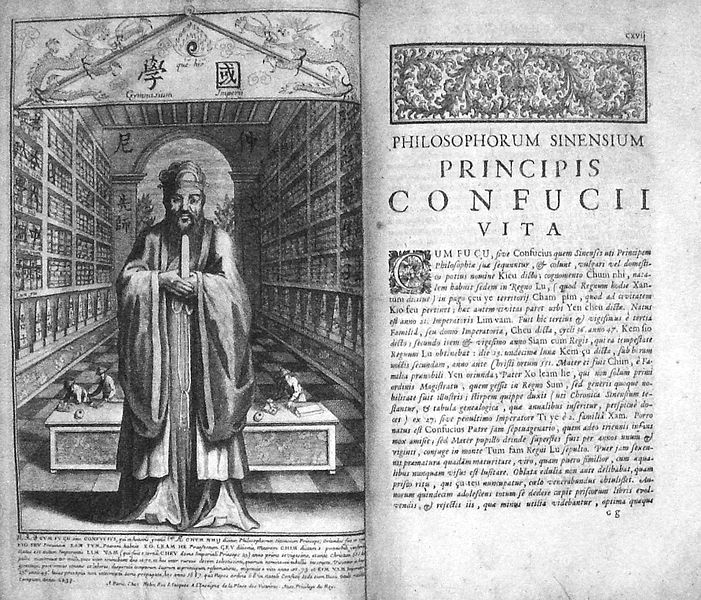

Confucius Sinarum Philosophus, published in Paris in 1687 by Jesuit missionaries Philippe Couplet and Prospero Intorcetta, is the first work that brought the Confucian canon to Europe.

It is commonly believed that the pre-modern China was largely under the prevailing influences of Western civilization. However, if we extend the study over a long length of time, we would discover a period worthy of scholarly attention, during which continental Europe admired and emulated Confucian ideas and other aspects of Chinese culture. From the 16th century to the 19th century, the scenario of cultural exchanges between China and the West reflected the early development of Sinology in Western countries.

Researches on Western Sinology

In the last two decades, Chinese academia has made remarkable achievements in areas that are germane to Sino-European relations.

From 1980s on, a project “Translation Series on China-Foreign Relations” led by Xie Fang started translation and compilation of crucial texts relevant to Sino-foreign relations. Chinese versions of Mateo Ricci’s Sketches of China, Juan Mendoza’s Historia del Gran Reino de la China (A History of Chinese Empire), Álvaro de Semedo’s Imperio de la China (Records on Chinese Empire) were made available. Moreover, a series of studies on China completed between the 16th and the 18th century were published through the joint efforts of Da Xiang Press and National Research Center of Overseas Chinese Studies at Beijing Foreign Language University.

Major methods of investigating Western Sinology included collecting, compiling and examining textual materials. As Yan Shaodang, a well-known professor of language and literature from Peking University said: “Research on Western Sinology should start with the primary materials. Without primary research, studies on Western Sinology are no more than castles in the air.”

Looking back over the past 30 years, the field has been replete with impressive intellectual achievements, including Series of the Global Adventures of Chinese Literature edited by Zhou Tianxiang, Yan Zonglin’s Missionaries and Early French Sinology, Li Tiangang’s Confucian Rites in Dispute: History, Texts and Significance, Lin Jinshui’s Mateo Ricci and China, Zhang Guogang’s Missionaries and European Sinology during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Ji Xiangxiang’s A Study on Mid-17th Century Sinological Works, Zhang Xiping’s A History of Early European Sinology, and Yan Guodong’s A History of Russian Sinology. These monographs shed light on how imperial China was studied and understood in different European countries.

Classics translation

Through this groundbreaking research, a once-neglected area has been revived. To be brief, in that era, Chinese culture and Sinology had a profound influence on the Enlightenment and Western thought at large, and missionaries played a pioneering role. It can be safely concluded that research on Western Sinology has formed one of the most active areas within Chinese academia in the past three decades. The cultural and intellectual significance of Western Sinology will become more apparent if we examine it in a broader historical context.

For one, studies on early Western Sinology have enriched the field of modern Chinese history because records left by missionaries not only testify to the spread of Christianity in China but also elucidate the nation’s political, social, economic and cultural circumstances since late Ming Dynasty.

In this light, the collation and compilation of Western records on late imperial and pre-modern China are necessary and fundamental to various fields of historical research. To be more specific, these records include Western publications as well as unpublished archives, documents and manuscripts relevant to China.

Second, research on Western Sinology details how Chinese classics have been translated in Europe, which began in the reigning period of the Wanli Emperor in the late Ming Dynasty. The Italian missionary Michele Ruggieri was the first to introduce Chinese classics to Western audiences.

He translated a short section of The Great Learning (Da Xue) into Latin and then published it in Europe. Starting with Mateo Ricci, who adopted the adaptive approach to Chinese culture, Jesuits have considered the translation of classical doctrines to be of critical importance. The Belgian missionary François Noël was considered the most accomplished translator among all the Jesuits. By virtue of his efforts and talent, The Great Learning, The Analects (Lun Yu), The Golden Mean (Zhong Yong), Mencius (Mengzi), The Book of Filial Piety (Xiao Jing) and The Primary Learning (Xiao Xue) were rendered into Latin and codified into the Great Canon of the Chinese Empire.

Moreover, The Book of Changes (Yi Jing), The Book of Songs (Shi Jing), the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chun Qiu), and The Book of Documents (Shang Shu) were abridged and translated into several European languages by various Jesuits. It seems that The Book of Changes attracted particular attention because dozens of its translated versions appeared in Europe.

Since 1840 when many protestant missionaries came to China, a new generation of extraordinary Sinologists emerged among them. In cooperation with Wang Tao, an intellectual from Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, the British missionary James Legge translated and published several classical doctrines, such as The Great Learning, The Analects, The Book of Documents and The Book of Filial Piety. His versions continue to be indispensible for contemporary translators specializing in the field.

The German missionary Richard Wilhelm was also dedicated to the same cause when he was in China. His translation of The Book of Changes has been particularly well received because of the generous assistance he had from Lao Naixuan, a Qing loyalist. The translations of The Book of Songs, carried out by British sinologist Arthur Waley and his Swedish counterpart Bernhard Karlgren, are too impressive to be ignored. Without doubt, an ample knowledge on relevant chapters in translation history can facilitate better renditions of these timeless classics today.

Finally, an in-depth understanding of Western Sinology will enable us to reevaluate the contemporary relevance of Chinese culture in the context of reciprocal exchanges without being derailed by a disproportionate orientation toward Western scholarship. Europeans no longer acknowledged their debts to other civilizations after taking over the world in the beginning of the 19th century. However, as a matter of fact, it is unlikely that they would have prevailed in the clashes between civilizations without actively learning from the Islamic world and China in previous centuries.

East-West dialogue in broader context

Islam stimulated the Renaissance era while China helped shape the Enlightenment. Europe was once characterized by a humble spirit of learning, as evident in Leibniz’s perceptions on Chinese culture and Voltaire’s narrations of global history in Essaisur les moeurs et l’esprit des Nations (Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations).

Sadly, Europe forgot its apprenticeship after surpassing the mentors. Intellectuals became inclined to invent and propagate myths, such as so-called “universal values,” which are by no means universal but abstract distillations of limited local experience, knowledge and ideas. Such an unreasonably egoistic tendency is most manifest in Max Weber’s writings.

It is undeniable that the West has contributed an enormous amount of valuable ideas to humanity as a whole in the course of modernization. However, Western civilizations did not grow and thrive in a vacuum. A self-aggrandizing attitude is not only at odds with historical facts but also contradicts the cultural tradition of learning.

As history unfolds, the century-old cultural and political status quo molded by the West will inevitably undergo dramatic transformation. With China reclaiming its due place in the family of nations, East-West exchanges and dialogue will be conducted on a more equal footing. Looking back on the past 400 years of communication between the East and the West, we are obliged to reexamine and reinterpret Sino-Western contacts and relations from a holistic perspective.

In this vein, studies on early Western Sinology can ensure a clearer view on the changing reality of modern Western thought that provides an ultimate relief from the deadlock of rigid dichotomies, such as tradition versus modernity and East versus West. The result will be a more extensive reconsideration of the historical and realistic significance of Eastern civilizations.

Zhang Xiping is a professor from Beijing Foreign Studies University.