Traditional politics best understood through royal power

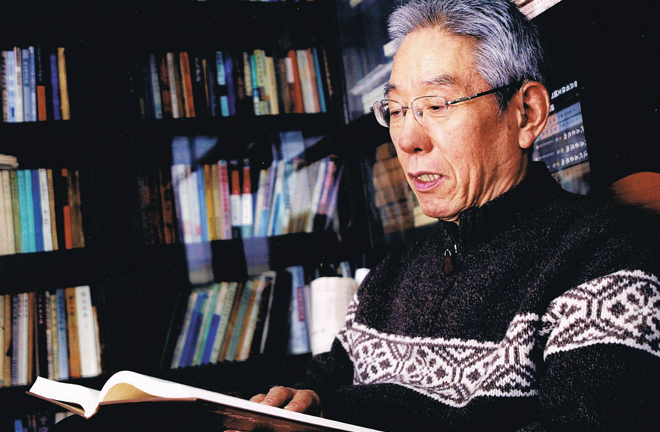

Liu Zehua, a professor of ancient Chinese history at Nankai University

Professor Liu attends the press conference and academic seminar of General History of Chinese Political Thought at Nankai University.

Zehua (1935- ) is a professor and doctoral supervisor in the Teaching and Research Office of Ancient Chinese History at Nankai University. He has served as the director of the Department of History at Nankai University and made great contributions to the study of history of Chinese political thought and political culture. He is the author of the History of Political Thought in the Pre-Qin Period and Rethinking Chinese Traditional Political Thought.

How to properly preserve and carry on the legacy of China’s cherished cultural traditions is a theoretical and practical question. In September 2014, China Renmin University Press published nine volumes of Liu’s General History of Chinese Political Thought, a masterpiece that systematically organized the history of Chinese political thought using a unified schema of history and methodology. His book provides us an important reference for scientifically understanding traditional culture and its contemporary significance.

Recently, a CSST reporter interviewed Liu on traditional Chinese political thought and traditional culture.

CSST: In the 1980s, Hongqi magazine published your article “Historiography Should be Concerned With the Destiny of Nationalities and Humans,” which stirred broad debate throughout academia. What are your opinions about the issue of “destiny” in historiography?

Liu: The changing times will make people rethink history, and this is done for the sake of looking to the future. This is why historiography should be concerned with issues of “destiny.” When “Historiography Should be Concerned With the Destiny of Nationalities and Humans” was published, some people said that this article has elevated historiography to such a lofty position while others asserted that many issues in historiography have little or nothing to do with “destiny,” and this attitude has limited the scope of historiography.

In fact, what I said is that we “should be concerned,” and I didn’t exclude other possibilities. As a means of understanding history, I still insist that we should be concerned with the issue of “destiny.” If we abandon the conceptual framework of “destiny,” historiography would lose its structure and become formless, making it no longer a serious discipline but only gossip.

CSST: If we analyze further, how can traditional Chinese society be categorized in terms of social formation? How should we treat and interpret the historical essence of traditional Chinese society and political thought?

Liu: Just as I said previously, the issue of “destiny” is not about some people’s personal opinions and regulations but the inevitability of the course of history. The recognition of inevitability needs to be demonstrated and probed repeatedly by many people, and then it would be probably become clearer step by step. If we just think of history as only the accumulation of accidents, then there is nothing to discuss with regard to issues of “destiny.” I think that history has its own inevitability and regularity.

So it is difficult to generalize about social formation, and I have stressed that we should conduct layered research and comprehensive analysis of traditional Chinese social formation. We need to differentiate issues at three levels. The first is the fundamental issue of social relations. The second is the issue of social control and operating mechanism. The third is the issue of social ideology and paradigm.

With respect to the issue on the first level, in the historical period during which the forces of social production developed slowly and before the productivity break through, the existing social relations and social activities were mainly driven by contradictions among daily social interest relations. There is no doubt that social interest encompasses many fields, but the primary is economic interest.

In the thousands of years of traditional Chinese society, economic interests have not primarily been achieved by economic means but by political means or political power. In this way, political power has come to the center of the historical stage and played a leading role in social control and activity for a long time.

For the second level, the ancient Chinese social structure belongs to the framework “authority-appendage,” which permeated social life in every aspect. This made every social role except the emperor’s equivalent to that of a slave.

For the third level, corresponding to the generalized “authority-appendage” social structure, there was an absolute worship of authority in ancient China. In order to maintain absolute authority of social politics, the master-slave relationship came into being.

CSST: Studying political thought refers to ideas of politics or political power. In Chinese history, what kind of role has politics or political power played in history? How can we understand and grasp the historical essence of Chinese traditional social structure and the gist of political thought?

Liu: Previous studies of the history of political thought focused on either political thought itself or real politics and systemic problems. But my research pays attention to both these areas and attempts to combine them to explore their impact on society as a whole. That is to make an integral historical observation and theoretical thinking.

In the course of Chinese history, politics has played a significant role, and kings and emperors had supreme control over their subjects and resources. It is an undeniable matter of fact that the monarchy dominated society. Correspondingly, political thought was foremost among social ideas, and the monarchy was the central feature.

On the basis of systematic research and comprehensive reflection, I have concluded that the essential feature of traditional society was that the monarchy dominated society and the guiding idea was royal power.

CSST: In the 1980s, you have written a book Autocratic Power and Chinese Society with your students. What does the royal power refer to in that book?

Liu: The royal power to which I am referring contains three aspects.

The first refers to its institutions, mainly the system of political institutions.

The second is the relation between the monarchy and society, which mainly emphasizes the dominance of the king over society.

The third is that the mainstream of Chinese traditional political thought refers to the domination of kings and emperors and the subordinate status of their subjects.

CSST: What is the contemporary value of traditional Chinese thought? What do you think about the phenomenon of promoting and reviving traditional culture in today’s life?

Liu: In my opinion, traditional thought is primarily a resource and the key to developing and utilizing this resource is to innovate the “self.” First of all, ancient Chinese people have put forward many concepts that we can develop. For example, “people oriented,” “rule by law,” “rule of law,” “harmony,” “evil human nature,”“good human nature” and there are too many to list. The concept is a sort of advanced human abstract cognition that can be extracted from the entire intellectual framework to develop our own ideas. Secondly, we can borrow predecessors’ concepts.

The concept is the “knot” of cognition and only connecting “knots” can weave a net. The history of human cognition demonstrates that a concept experiences a gradual reformation process but considerable portions of concepts are inherited from predecessors. Many concepts we are using now come from ancient people.

From the literal perspective, words or phrases can be the same but their meanings can be amended, complemented or even remade. Moreover, we can seek wisdom and reference by analyzing ancient people’s answers to various questions and the actions they took to solve these problems. The ideas of ancient people on the self and beyond the self have provided a reference for the real problems we face.

Lastly, we can take in certain methodologies with scientific significance. Given a wealth of ideas to draw upon, we cannot keep the old thought as it was in the same manner as one would protect cultural relics to preserve their original characteristics. And the core is to develop and innovate the thought. We should calmly analyze today’s phenomenon to “promote” and “revive” some traditional culture and pay close attention to what traditions should be “promoted” and “revived.”

Zhang Qingli is a reporter at Chinese Social Sciences Today.