Turmoil on the sea led to fall of Yuan dynasty

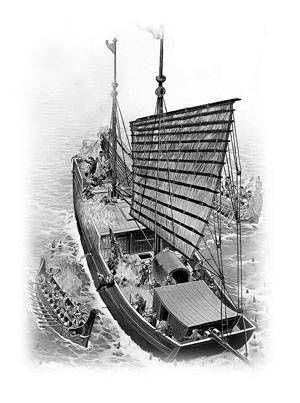

Pictured here is an artist’s rendering of a small pirate ship battling against government troops in the late Yuan dynasty.

The prevailing wisdom as to why the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1616-1911) dynasties kept their marine borders closed attributes this to the conservative nature of the people in those eras, who lived in a small-scale peasant economy and stubbornly adhered to old ideas and rules.

But the truth of the matter is that the policy was also related to the collapse of the Yuan dynasty (1206-1368). The turbulence in the southeast sea led to the decline of the powerful and prosperous Great Yuan Empire, leaving behind a lesson that was not soon forgotten by its successor the Ming dynasty.

However, why did the Yuan regime, after opening its marine borders to the outside world, ultimately succumb to turmoil on the seas? An examination of policies regarding marine economy may hold clues.

Maritime interests

The Yuan dynasty witnessed a boom in its marine economy. Starting with the unification of southern China, the Yuan government made policies to support maritime trade. After occupying the coastal areas of what is now Zhejiang and Fujian provinces, Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty, whose reign spanned from 1260 to 1294, made a proclamation allowing trade and exchanges with overseas countries.

Modeled on the system of its predecessor the Song dynasty (960-1279), the imperial court established bureaus for foreign shipping to manage trade in ports, such as Guangzhou, Guangdong province and Quanzhou in today’s Fujian province. It also enacted laws containing detailed regulations on banned goods, gambling transactions, customs duties, smuggling, punishments and management of vessels.

In order to maximize its profits in overseas trade, the Yuan dynasty also introduced a system of vessels funded by the government and operated by merchants on a commission basis. The profits would be shared between the government and merchants at a ratio of 7-to-3. The vessels were bound by the laws of the bureaus for foreign shipping and paid taxes as required, affirming the legitimacy of overseas trade by the government.

The fishing and salt industries were important parts of marine economy and provided traditional occupations for coastal residents. As recorded in the History of Yuan Dynasty, the fishing industry flourished at the time, and rare articles such as sharkskin were paid as tribute to the capital.

The broad intertidal zone in the southeast had long served as a major production area of sea salt. The Yuan dynasty continued to use the salt works of the Song dynasty and improved manufacturing technology to increase yield.

With a monopoly on sales, the government was able to generate colossal incomes. Records show that the Yuan dynasty levied a tax rate on sea salt several times higher than the previous dynasties, which helped to fund the construction of the nation.

For the Yuan dynasty, the ocean was not merely a source of finance and taxation but essential to its survival. Khanbaliq, the capital of the Yuan dynasty, located on the edge of the North China Plain in what is now Beijing, was so crowded with noble families, bureaucrats, armies, residents and artisans that the supply of food fell far short of meeting local demand.

In response to the situation, the Yuan government opened a shipping line from the southern ports to Khanbaliq. The sea transportation of food from the southeast had become a matter of life and death for the Yuan Empire.

Public welfare ignored

The Yuan government sought to develop and harness the ocean to strengthen its reign rather than to promote the local economy and increase the people’s wealth. The imperial court tried every possible means to control overseas trade because of its massive profit.

The system of government-funded ships was such an example. In order to monopolize trade, the Yuan government prohibited merchants from private foreign trade. Moreover, bureaus for foreign shipping in some places, like Wenzhou in modern-day Zhejiang province, were abolished, and the incomes of private shops were confiscated, forcing merchants to join the government-run system.

Smuggling combined with the plundering of the empire’s revenue by official fraud undermined the system of government-funded vessels, forcing the Yuan government to allow private business once again. At the same time, it adopted restrictive measures, such as strict examinations of ships, staff and goods, inspections for contraband, as well as limitations on shipping routes and dates of departure and return. Moreover, officials used the restrictions as a pretext to extort merchants, driving many into bankruptcy.

The Yuan government also tightened its control over the production and sale of sea salt, requiring households engaged in the salt industry to get authorization to change occupations from generation to generation. The government had the right to purchase sea salt at a very low price, and households failing to fulfill quotas would be subjected to severe punishments. To prevent smuggling and avoid losses in tax revenue, the government mandated that taxes be collected based on the registered permanent residence at salt works and coastal areas. As a result, many households and coastal residents went bankrupt and became fugitives. And some even took up arms.

Fishermen in the Yuan dynasty not only faced the risk of shipwrecks but were also forced to use their ships for transportation. Local governments ordered fishing boats to transport food with a disregard for the safety of fishermen. If an accident took place, even if the fisherman survived, he was financially responsible for the loss.

In the late Yuan, corruption and social crisis greatly devalued the currency. Some officials even pocketed the wages of fishermen. Some fishermen were so destitute that they had to sell their own children, and many others were forced to flee their homes.

Incurring resistance

Though the Yuan dynasty recognized the reliance of its reign on overseas trade as well as the sea salt, fishing and sea transportation industries, its marine economic policies failed to benefit the common people. Instead, official corruption, heavy taxes and strict regulations caused extreme misery to citizens living off vital coastal industries.

Thus, a segment of the seafaring population began to flout the government’s authority, depriving the Yuan dynasty of its control over the sea. An armed group engaged in salt smuggling and interruption of the food transportation on water appeared in the southeast sea, precipitating the decline of the Yuan dynasty.

The failure of the marine economic policies and the turmoil arising on the sea originated from the ruling policies and cultural characteristics of the Yuan dynasty. It adopted a hierarchical system that divided different ethnic groups into four classes.

The residents living along the southeast coast belonged to the lowest class, which was kept under strict control and burdened with heavy taxes. The purpose of the Yuan dynasty developing the marine economy was not to improve their livelihood but to squeeze their earnings.

These coastal residents risked their lives in the mountains and on the sea all the year round, making them organized and fearless. By contrast, officers and soldiers garrisoned in the coastal area came mostly from the north and thus were bad at naval battles and afraid of pirates. They usually bullied the people living in villages but panicked when they encountered pirates in large numbers.

In light of such classification, the people of the coasts chose to join the anti-government forces. The Yuan emperors were prairie people who didn’t have enough experience in navigation to handle the marine disturbance. In the late Yuan, more and more coastal residents began to revolt, enlarging the rebellion. As a result, what seemed like a carefully constructed defense mechanism soon fell apart, breaking off its lifeline.

Though the Ming dynasty learned from the Yuan dynasty, it was not aware of the root cause of the Yuan dynasty’s downfall. With a ban on maritime trade, the Ming dynasty avoided repeating the Yuan’s mistake, but it also brought to a halt the progress that Chinese society had made toward openness since the Tang and Song dynasties.

Chen Caiyun is from the East China Sea Rim and Culture Research Institute at the Zhejiang Normal University.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 657, October 17, 2014.

Translated by RenJingyun

Revised by Justin Ward