Ancient glass beads found in Xinjiang reveal Mediterranean ties

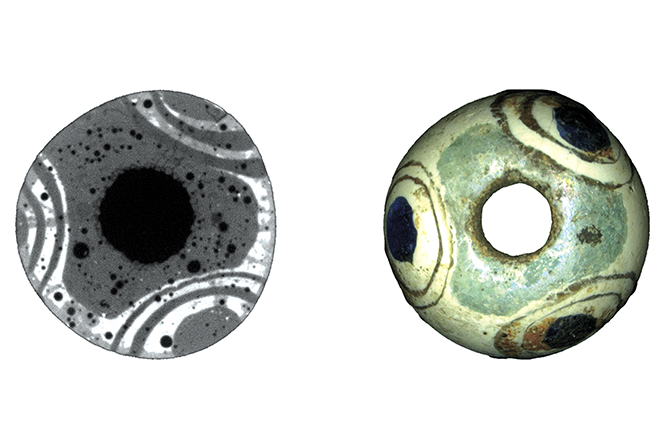

CT scans (left) and physical specimen (right) of a dragonfly-eye glass bead unearthed in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

In the early Iron Age tombs along the Tianshan Mountains in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, glass beads and other ornaments made of various materials—diverse in form and vibrant in color—are commonly discovered. Based on their burial contexts and associated evidence, these ornaments were likely used as necklaces or bracelets. In traditional archaeological research, such bead ornaments have often been overlooked and seldom subjected to detailed analysis. Yet these seemingly ordinary items hold considerable scholarly value. Chinese archaeologist Xia Nai’s study of Egyptian bead ornaments is a landmark example of what such research can reveal.

Ancient bead ornaments unearthed along the Silk Road in the Tianshan region exhibit striking diversity in form, material, and craftsmanship. Among them, a distinctive group of glass beads known as “dragonfly-eye” beads—found in early Iron Age tombs such as the Jartai Pass cemetery in Nilka County and the Alagou cemetery in Urumqi, Xinjiang—has drawn growing academic interest. These beads show a high degree of uniformity in shape, design, and coloration. Typically made from light green or white glass, their surfaces are decorated with layered concentric circle patterns featuring black or brown “eye rims,” opaque white “sclerae,” and dark blue “pupils.”

Recently, using a combination of advanced analytical techniques—including Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS), Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (LA-ICP-AES), and micro-CT scanning—we conducted a systematic study of the beads’ raw materials, origins, and manufacturing techniques.

Identifying natron glass through compositional analysis

In the study of ancient glassmaking, analyzing chemical composition to identify the fluxing agents used is key to understanding both production techniques and provenance. Our analysis confirms that the dragonfly-eye beads from Xinjiang are made of typical natron glass. Their chemical composition shows low levels of magnesium oxide (MgO) and potassium oxide (K2O)—each under 1.5 wt%—which aligns closely with the signature of natron glass.

Natron glass is a type of soda-lime glass made using natron sourced from salt deposits in Egypt’s Wadi El Natrun and al-Barnuj as a fluxing agent. This glass type first appeared in Egypt around 1000 BCE and subsequently spread to Mesopotamia, the Mediterranean coast, the Levant, and Europe. By the 5th century BCE, it had become the dominant form of glass west of the Euphrates River, laying the foundation for the Roman Empire’s thriving glass industry.

From the late Spring and Autumn Period through the Warring States Period, natron glass products began to appear in China. They have been found in regions including Hubei, Henan, Gansu, Yunnan, and Xinjiang, with dragonfly-eye beads being the most common form. Earlier studies suggested that this early natron glass found in China originated in the Mediterranean region. However, scholarly views diverge on the specific transmission routes by which it reached China—particularly Xinjiang.

Revealing manufacturing techniques with micro-CT imaging

To investigate the internal structure and manufacturing process of these valuable ancient beads without causing damage, we used micro-CT scanning to create non-destructive images of well-preserved dragonfly-eye beads. These scans clearly reveal their internal features. Based on the imaging results, we infer that their production involved three main steps:

Step 1: Fabricate the “eye” design. Craftsmen did not apply the eye pattern directly onto the bead but instead pre-fabricated it in layers: a dark blue core, a white sclera layer, and a dark-colored rim or eyelid layer.

Step 2: Shaping the bead body. A light green glass bead body was formed and then coated with a layer of white glass paste. This white coating is a key feature visible in CT images that indicates the use of an inlaying technique.

Step 3: Inlaying the “eye.” The bead body was continuously heated to a semi-molten state, at which point the pre-formed “eye” component was carefully pressed or embedded into its surface. As the bead cooled, the “eye” became securely fixed into the body. This layered manufacturing technique was commonly used in the production of early dragonfly-eye beads.

Tracing origins through trace element analysis

High-quality, high-precision trace element analysis is essential for determining the geographical origin of ancient glass. These geochemical “fingerprints” serve as reliable evidence for identifying source regions. Using LA-ICP-MS technology, we obtained trace element data from samples of natron glass excavated in Xinjiang. We then systematically compared the major and trace element compositions of these samples with natron glass data from the first millennium BCE, established through extensive international archaeological research. This comparison encompassed several key production centers, including Egypt, the Levant, and early European sites.

The results of the comparative analysis were strikingly specific. The Xinjiang samples displayed consistent elemental profiles, most notably a high strontium (Sr) content exceeding 300 ppm and a positive correlation with calcium oxide (CaO), indicating a marine sand origin. Their trace element patterns closely matched those of known natron glass from the Levant—particularly from the coastal regions of present-day Syria and Palestine—strongly suggesting that these beads were produced there.

Remarkably, these Levantine dragonfly-eye beads reached Xinjiang centuries before Zhang Qian’s famed westward expedition during the Western Han Dynasty. This discovery pushes back the timeline of Mediterranean cultural influence in western China to the mid–first millennium BCE, offering compelling material evidence of East–West interaction predating the formal establishment of the Silk Road.

A new look at the eastern transmission routes

The journey of natron glass beads did not end in Xinjiang. Where did they go next? To explore their further eastward transmission, we compared samples from Xinjiang with similar beads unearthed from Warring States–Period tombs at Majiayuan in Gansu and sites in Hubei Province—including the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Jiulian Dun, and Jiudian Cemetery. Strong similarities were found in both chemical composition and decorative patterns. Some beads from Hubei and Gansu are nearly identical to those from Xinjiang and also fall within the Levantine natron glass category.

These findings suggest a transmission route extending from Xinjiang along the Tianshan corridor to Gansu, and from there into central China. The repeated discovery of such beads at multiple Xinjiang sites points to a sustained and widespread transmission rather than isolated occurrences. Simultaneously, Xinjiang has yielded other glass types, including plant ash–fluxed soda-lime-silica glass from West Asia, lead-barium glass from the Central Plains, and Chinese blue-glazed wares—together demonstrating Xinjiang’s role as a dynamic hub of East–West material exchange in the first millennium BCE.

Elemental analysis also reveals certain divergences among the natron glass samples from Hubei. Some early Warring States examples show strontium (Sr) levels below 300 ppm, suggesting the use of inland sand rather than marine sand, and pointing to a different origin from Levantine natron glass. Even greater variation is observed in the natron glass found in Yunnan. These distinctions suggest that natron glass may have reached inland China via multiple routes: one confirmed path passed through the northwestern corridor via Xinjiang and Gansu, while other possible routes include a direct overland path through the Eurasian steppes and, later, transmission via the Southwest Silk Road into Yunnan.

Understanding the existence of the northwest corridor requires placing it within the context of the rise of Eurasian steppe nomadic cultures during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. During this time, Xinjiang entered the late phase of the early Iron Age, and the integration of Eurasian steppe nomadic cultures accelerated. With the rise and diffusion of nomadic cultures, the range of activities of the local populations broadened significantly, greatly facilitating the circulation of material goods and cultural exchange between the East and West of the Eurasian continent. The transmission of iron and iron smelting technology from West Asia and Central Asia through Xinjiang and the Gansu-Qinghai regions to the Central Plains serves as a significant example. Meanwhile, silk textiles, lacquerware, and bronze mirrors from the Central Plains also spread to Central Asia via the Western Regions. The silk embroidered fabric with Chu cultural motifs excavated from the Alagou cemetery in Xinjiang, along with Central Plains silk, bronze mirrors, and lacquerware discovered in the Pazyryk burials on the northern slopes of the Altai Mountains, provide important material evidence of this exchange. Therefore, the appearance of Levantine natron glass beads in the Tianshan region and their continued eastward spread parallel the westward movement of iron and silk, forming a crucial chapter in the history of material and cultural exchange between East and West during the first millennium BCE. Xinjiang was a key node in this exchange network, linking distant civilizations across Eurasia.

The technological and archaeological study of natron glass beads from early Iron Age Xinjiang thus offers new insight into the origins and trajectories of early East–West exchange. Scientific analysis confirms their Levantine origin, while comparative research on composition, manufacturing techniques, and stylistic features with Chinese finds provides robust evidence for their transmission route through Xinjiang and Gansu into the Central Plains.

Once introduced, Chinese artisans quickly assimilated and adapted foreign glassmaking techniques, laying the foundation for a distinctive domestic glass industry. During the Warring States Period, craftsmen used native lead and barium minerals to produce local imitations of dragonfly-eye beads, eventually creating glass bi discs and jade-like ornaments. This led to the emergence of an independent lead-barium glass system, technologically distinct from Western traditions.

The long-distance transmission and evolution of glassmaking technology from West to East vividly illustrates the scale and depth of early Eurasian civilization exchange and mutual learning. These findings not only provide new archaeological evidence for the inclusive and innovative nature of Chinese civilization but also underscore Xinjiang’s pivotal role as a gateway for cross-cultural interaction between East and West.

Liu Nian is an assistant research fellow from the Key Laboratory of Archaeological Sciences and Cultural Heritage at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG