Tracing the evolution of early dragon imagery through archaeology

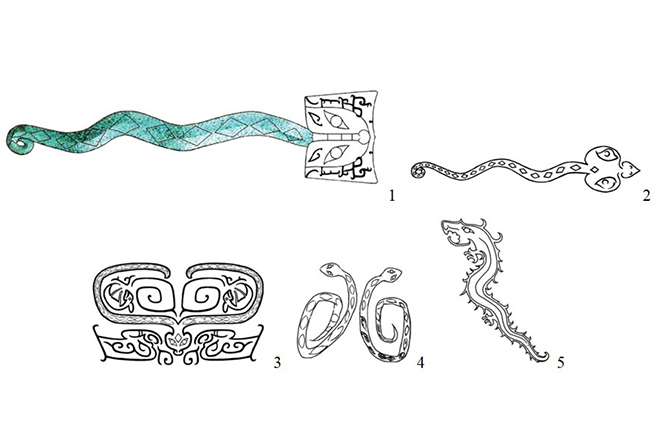

The restoration drawings of the turquoise dragon-shaped object unearthed from the Erlitou site (1), the snake-like pattern on the pottery vessel (Ⅴ·ⅡT107) from Erlitou (2), the double-bodied snake image on the pottery fragment from pit VT212 (3); the image on the hollow-based vessel (ⅣT17②:4) from Erlitou (4), and the snake-bodied creature on the hollow-based vessel (ⅤT210④B:3、ⅤT212⑤:1) from Erlitou (5) Photo: PROVIDID TO CSST

A turquoise dragon-shaped object unearthed from the Erlitou site at Yanshi, Henan—regarded as the capital city in the late Xia Dynasty (c. 21st century–16th century BCE)—is renowned for its exquisite craftsmanship. Meanwhile, at the Taosi site in Xiangfen, Shanxi, often identified as the legendary capital of Emperor Yao, four plates featuring painted dragons were discovered, dating back to 2,600–2,000 BCE.

At the Chinese Archaeological Museum of the Chinese Academy of History, visitors can admire both the turquoise dragon-shaped object and the painted dragon plates. Yet one might wonder: the so-called “dragon-shaped” object and the “dragons on plates” bear little resemblance to the dragons of later tradition—lacking horns or claws, they look much more like snakes. Why, then, are they identified as dragons? To answer this, we must trace the evolution of dragon motifs in early Chinese history.

Shang and Zhou dragons featuring ‘bottle-shaped’ horns

The image of the Chinese dragon had largely taken shape by the Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Zhou (c. 1046–256 BCE) periods. Therefore, the dragon motifs of these periods are not only the direct precursors of later depictions but also offer a foundation for tracing their origins further back.

Shang and Zhou dragon motifs exhibit several distinct features. Most are horned, typically with “bottle-shaped” horns—features unique to Chinese dragons and absent in other animals. Some dragons also bear T-shaped horns, though these are not exclusive to dragons. T-shaped dorsal fins are another unique trait found only in Chinese dragons. Some features, however, are shared with other animal representations. For instance, rhomboid (diamond-shaped) forehead markings—a sacred symbol—appear on dragons as well as on depictions of bulls, tigers, and snakes. Many dragons display rhomboid patterns along their backs. While this symbol mainly appears on dragons during the Shang and Zhou periods, a bronze snake from the Sanxingdui site also features rhomboid patterns on its back.

Dragons are mythical creatures modeled in part on real animals. Over time, dragon imagery absorbed features from a range of creatures. Judging from Shang and Zhou examples, the snake appears to have been the primary prototype for the Chinese dragon. Three subtle clues point in this direction. First, the dragons depicted on late Shang coiled-dragon plates and dragon-decorated gong vessels have long, slender, winding bodies without claws—forms that clearly evoke snakes. Second, their bodies are often covered in rhomboid scales, closely resembling the diamond-shaped dorsal scales found on snakes such as pythons and pit vipers. Third, frontal views of dragon heads, as seen on certain coiled-dragon plates, reveal split lower jaws—anatomically consistent with the two-part jaw structure of real snakes.

In addition, Shang and Zhou dragon motifs incorporate features drawn from other animals. Their T-shaped dorsal fins may have been inspired by the bony ridges of crocodile backs, and their ears often resemble those of tigers. Some even feature tiger heads.

As divine creatures, dragons must be visually distinguished from real animals such as snakes or crocodiles. Thus, we may conclude that dragons are the mythologized forms of snakes or other reptiles. Any animal image possessing either bottle-shaped horns or T-shaped dorsal fins can be considered a dragon; similarly, snake-like bodies augmented with horns, ears, or claws also qualify, as these additions deviate from real snakes. Rhomboid forehead ornaments, rhomboid back decorations, and T-shaped horns are also key identifiers of dragons.

Erlitou culture affirms the snake as the dragon’s main prototype

The Erlitou culture (c. 1800–1500 BCE), typically associated with the late Xia Dynasty, produced the iconic turquoise dragon-shaped artifact at its central capital site. The creature’s body is distinctly serpentine, adorned with rhomboid patterns. Its large, shovel-shaped head features a segmented nose bridge (crafted from green and white jade), and a bulbous turquoise snout, a split lower jaw, and no visible claws or horns. The snake-like body, rhomboid back motifs, and split jaw are all hallmarks of real snakes. However, its exaggerated nose bridge and snout diverge from real serpents, indicating a mythologized or divine transformation—a dragon, not a snake.

In addition to the turquoise artifact, several other relics unearthed at Erlitou feature dragon or snake motifs. A pottery vessel (Ⅴ·ⅡT107) displays snake-like patterns, including rhomboid designs on the forehead and back, and a prominent snout reminiscent of the turquoise dragon. A pottery fragment from pit VT212, when reconstructed, depicts a double-bodied snake with similar rhomboid designs. Another piece—a hollow-based vessel (ⅤT210④B:3、ⅤT212⑤:1)—is adorned with a fantastical snake-bodied creature with claws and dorsal fins, unmistakably departing the realm of real snakes and thus identifiable as dragons.

These rich snake motifs discovered at the Erlitou site reflect a culture of serpent worship among Erlitou people. Furthermore, the progression from snake patterns to dragon motifs—also evident from later Shang and Zhou examples—supports the conclusion that the snake was the dragon’s primary prototype.

The continuity between Erlitou and Shang-Zhou dragon motifs is striking. Coiled and crawling postures, single or paired dragons, single-headed or double-bodied forms—all appear in Erlitou designs. Horns, claws, and dorsal fins begin to emerge, even as many figures still closely resemble snakes. Rhomboid forehead and back patterns, along with split jaws, are preserved in later Shang and Zhou representations, showing that their dragons evolved directly from Erlitou’s dragon-snake hybrids.

Longshan era helping trace origins of dragon imagery

The Longshan era (c. 2300–1800 BCE), which predates Erlitou, also yielded numerous dragon- or snake-like artifacts across several archaeological cultures—Xinzhai, Shimao, Taosi, and Late Shijiahe—helping us trace the roots of Erlitou’s imagery.

Xinzhai culture, generally regarded as a transitional phase between the Wangwan III and Erlitou cultures, is considered Erlitou’s immediate predecessor. A pottery lid from the Xinzhai site in Xinmi, Henan, features a shovel-shaped head, segmented nose bridge, bulbous snout, and split lower jaw—traits that closely mirror the Erlitou turquoise dragon, suggesting direct cultural continuity.

At the Shimao site in Shenmu, Shaanxi, stone carvings on the Huangchengtai (lit. the terrace of a royal city) depict dragons or snakes. Sculpture No. 8, in particular, features a shovel-headed, snake-bodied figure, nearly identical to the Erlitou dragon-shaped artifact. Sculptures No. 16 and 37 also feature snake patterns.

Four painted plates were excavated from high-status tombs at the Taosi site in Xiangfen, Shanxi Province. These plates feature coiled dragons (or serpents) with tongues extended. The dragons (or serpents) are modeled in curled form at the center of each plate, resembling the coiled dragon motif seen on late Shang Dynasty plates. The so-called “dragons” on the painted plates appear more akin to snakes, though the two protrusions on either side of their heads may represent horns or ears—features not found on real snakes. This suggests that the “dragons” of the Taosi culture were already beginning to diverge in imagery from serpentine forms.

Clearly, dragon/snake motifs from Xinzhai, Shimao, and Taosi cultures share ceremonial functions and visual traits with Erlitou culture. These findings from the Longshan Era demonstrate the transformation from snake to dragon imagery.

The evolution of the Chinese dragon was not a linear process. Prior to the so-called “Longshan Era,” dragon-related artifacts had already appeared in several archaeological cultures such as the Yangshao, Hongshan, Lingjiatan, and Liangzhu. However, it was the serpent and dragon motifs of Longshan cultures—particularly Xinzhai, Shimao, and Taosi—and the Erlitou culture that directly shaped the dragon iconography of the Shang and Zhou periods. From these, we can trace the central evolutionary thread of dragon imagery.

Among the pre-Longshan archaeological cultures, the Hongshan (c. 4000–3000 BCE) and Liangzhu (c. 5300–4000 BCE) discoveries are particularly noteworthy. The jade dragon carved from dark green Xiuyan jade from the Hongshan culture finds echoes in similar motifs during the Shang Dynasty. Scholar Zhu Naicheng once pointed out that the painted dragons from the Taosi plates likely drew inspiration from the Liangzhu culture of the Lake Tai region. The Liangzhu representations of serpent mouths, the diamond-shaped patterns on dragon heads, and horn-like appendages may all have influenced the dragon and serpent motifs from the Longshan era onward.

In short, from the Longshan era through the Shang and Zhou periods, we see clear evidence of continuity in the evolution of dragon imagery. The snake was the primary prototype, and the dragon emerged as a supernatural transformation of serpentine forms. For a time, dragon and serpent images coexisted. The divine creatures depicted on the Taosi dragon plates and the Erlitou turquoise dragon-shaped artifact clearly evolved from serpent motifs but were imbued with supernatural characteristics distinct from real snakes. Given their place in the same visual lineage as Shang-Zhou dragons, it is reasonable to identify them as “dragons.”

Chen Minzhen is a professor from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Beijing Language and Culture University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG