Chinese science fiction: three decades of cultural ascent

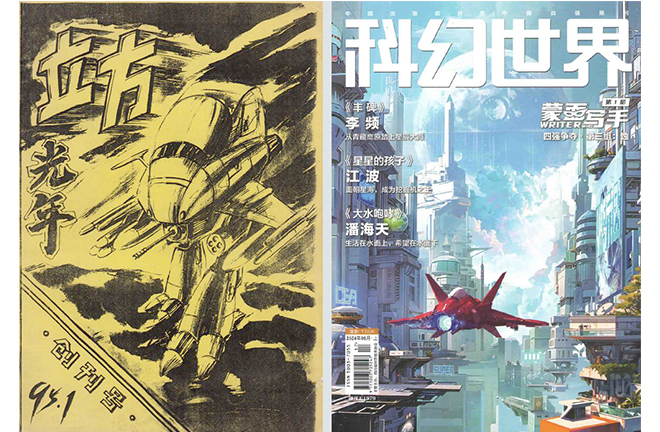

FILE PHOTO: The inaugural issue of Cubic Light-Year from 1995 (left) and the August issue of Science Fiction World from 2024 (right)

Since the 1990s, as China’s reform and opening-up policies have deepened, the country has witnessed the rapid emergence of bestselling publications and online literary platforms, fueled by commercial capital. Against this backdrop, the development of Chinese science fiction literature has entered a dynamic phase driven by multiple forces. The interplay of ideology, commercial investment, publishing institutions, and dedicated sci-fi fan communities has fostered a complex yet productive synergy that is propelling the genre’s growth in China.

Works imbued with Chinese elements

As a literary genre with foreign origins, science fiction in China has followed a unique trajectory of adaptation and evolution. In the early 20th century, Chinese sci-fi primarily centered on novel inventions, reflecting a fascination with technological progress. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, and under the influence of the Soviet Union, the genre took on an educational role, aiming to popularize scientific knowledge among young readers. This approach was often described as “conveying scientific knowledge in an artistic and vivid form.” It was only after the reform and opening-up that Chinese science fiction gradually shed its externally imposed didactic constraints, allowing writers greater freedom to engage with indigenous cultural narratives. Consequently, contemporary Chinese sci-fi has come to reflect the aesthetic sensibilities and literary traditions of Chinese readers, producing works deeply imbued with national identity and cultural heritage.

Since 1991, Science Fiction World magazine has published a series of novels drawing inspiration from mythology and history. These works seek to rediscover Chinese cultural traditions, employ sci-fi techniques to reinterpret national history, explore humanistic themes, and articulate intellectual anxieties about China’s evolving identity in an era of globalization. This creative approach has resulted in a literary tone distinct from that of Western sci-fi traditions. For example, Jiang Jianli’s Fuxi (1996) expresses a profound nostalgia for traditional Chinese culture, using a philosophical dialogue between ancient civilization and modern technological society to critique contemporary arrogance and restlessness. Yang Peng’s Space Three Kingdoms War (1997) reimagines historical anecdotes and myths from a futuristic perspective, weaving them into an original sci-fi narrative. Similarly, Pan Haitian’s Legend of the Puppet Master (1998) expands on the brief tale of “The Puppet Master Creates a Human” from the ancient Taoist text Liezi, transforming it into a modern tragic love story. Entering the 21st century, works such as Han Song’s 1938: Memories of Shanghai (2006), Fei Dao’s A View from the Top (2009), and A Que’s Conqueror (2015) have embraced the “alternative history” approach, reinterpreting classic Chinese stories while envisioning alternative historical trajectories.

Increasingly characteristic

For a long time, science fiction in China was categorized under children’s literature or popular science rather than being recognized as a distinct genre alongside martial arts and romance fiction. This perception began to shift in the 1990s, when sci-fi gradually secured stable publication platforms and cultivated a dedicated readership. By this time, writers had developed a deep understanding of publishers’ expectations and reader preferences, enabling them to craft works that aligned with the evolving tastes of their audience.

Perhaps the clearest marker of science fiction’s emergence as an independent genre is the rise of sci-fi fan culture as a subculture. Sci-fi enthusiasts share common interests, engage in frequent interactions, and even develop a specialized system of knowledge. In China, organized sci-fi fandom first emerged in the 1980s, but due to limited communication channels, it did not yet coalesce into a recognizable collective force. It was not until the 1990s that sci-fi fan groups became firmly established. Prominent sci-fi fan clubs appeared in cities such as Beijing, Tianjin, and Chengdu, with magazines like Nebula (Xingyun) and Cubic Light-Year (Lifang Guangnian) playing particularly influential roles.

Entering the 21st century, China’s sci-fi fan community has continued to expand, channeling significant enthusiasm and effort into promoting sci-fi activities. By this stage, Chinese science fiction has advanced alongside the global forefront of the genre, not only establishing itself as a major literary category but also fostering a vibrant and multifaceted sci-fi culture.

Lack of diverse publication ecosystem

While China’s sci-fi literature has made remarkable strides, it is equally important to acknowledge its underlying challenges. As discussed earlier, the contemporary sci-fi boom has been driven by multiple forces within China’s socialist market economy system. However, none of these forces are without flaws, and each presents certain limitations. Three key issues, in particular, merit attention.

The first is the lack of a diverse sci-fi publication ecosystem. China’s science fiction landscape undeniably benefits from renowned magazines that serve as crucial platforms for showcasing outstanding works and fostering new talent. Science Fiction World, for instance, occupies a dominant position and its importance in the current landscape is self-evident. Yet, an overly consolidated magazine ecosystem can also create challenges. While magazines with strong market presence contribute to the genre’s visibility, they can also become a double-edged sword. To sustain themselves in a market-driven environment, commercially operated magazines must cater to audience preferences. While explicit restrictions are rarely stated in calls for submissions, editorial selections tend to align in theme, style, and subject matter. Over time, aspiring contributors inevitably adapt their writing to these implicit expectations.

Some magazines have recognized that such a self-reinforcing cycle in content production may hinder diversity within the genre. In response, Science Fiction World has introduced specialized editions, such as the “Youth Edition” and the “Translated Edition,” to broaden the range of styles and themes. Nevertheless, contemporary Chinese science fiction still exhibits a notable degree of formulaic writing, subtly constraining creative breakthroughs and limiting the genre’s expansion in new directions.

Impulsive pursuit of profit in publishing

Over the past three decades, Chinese science fiction has evolved beyond its traditional role as children’s popular science literature, shifting towards higher literary value and embracing greater philosophical complexity. Its readership has expanded to a broader audience that includes both adults and young readers. Within this context, the dominant publishing model for full-length sci-fi novels involves serialization in magazines or online platforms before being released as books once they gain traction. For example, in 2006, Liu Cixin serialized The Three-Body Problem in Science Fiction World. After receiving widespread acclaim, Chongqing Publishing House published the first two volumes in 2008 and the final volume in 2010. The novel’s phenomenal success acted as a catalyst for sci-fi publishing, underscoring the genre’s immense potential and commercial value.

However, beneath this prosperity lie several concerns. Most Chinese sci-fi writers still work part-time, which limits their ability to produce high-quality works consistently. When driven by capital interests, many underdeveloped novels risk being rushed to market prematurely. While younger generations of sci-fi authors do manage to publish outstanding works, a significant portion of new sci-fi books are actually reprints of older works by veteran writers, artificially inflating the volume of recent publications. Additionally, in introducing foreign sci-fi to Chinese audiences, publishers tend to prioritize established classics or bestsellers, often relying on repackaging and reprinting older titles rather than translating and promoting new voices in the genre.

Ultimately, under the influence of consumer culture, all forms of artistic expression—including science fiction—inevitably bear the imprint of commercialization. The traditional functions of sci-fi literature, such as intellectual exploration and aesthetic education, are gradually being overshadowed by entertainment and consumerism. A persistent concern is that if publishers continue prioritizing short-term market trends and hastily churning out derivative works, an influx of low-quality publications could disrupt the literary ecosystem. Without careful stewardship, China’s sci-fi boom may rise meteorically, only to collapse just as abruptly—an outcome no true enthusiast would want to see.

Weakening of reflexivity

Serious literature is inherently reflexive; as a creative practice in which authors strive for artistic elevation or renewal, it necessarily engages in a self-referential dialogue with the existing literary landscape. Writers must innovate boldly, continuously challenging established literary paradigms to offer a richer intellectual and aesthetic experience. In contrast, genre literature does not emphasize reflexivity. Instead, it prioritizes mastery of established narrative conventions—such as the “cliff-jumping miracle” [a character falls off a cliff and miraculously survives, often gaining new martial arts skills or encountering a hidden master] or “power-up through poisoning” [a character is poisoned but, instead of dying, gains extraordinary strength or unlocks hidden potential] tropes in martial arts novels, as well as the “mistaken marriage” and “terminal illness” formulas in romantic fiction. The goal is to refine these conventions to perfection, allowing for minor embellishments but avoiding disruptive innovation, lest the reader lose the pleasure of encountering something simultaneously familiar and fresh.

Science fiction, straddling the divide between serious literature and popular genre fiction, finds itself in a particularly delicate position when it comes to handling reflexivity. Emphasizing reflexivity in science fiction does not mean rejecting popular appeal but rather recognizing the risk that capital and market forces, in the wake of the current sci-fi boom, may push formulaic writing to an extreme. This includes reliance on stereotypical character archetypes—villainous aliens, reclusive programmer protagonists, and mad scientists—as well as the overuse of parallel universes or time travel as convenient narrative shortcuts when plotting becomes difficult. Furthermore, the incorporation of fantasy tropes like mythical fantasy and harem romance in pursuit of instant gratification risks diluting the genre’s more serious intellectual dimensions.

After all, as a form of thought experiment, sci-fi is inherently a forward-looking literary endeavor. If it becomes mired in rigid genre formulas, the likelihood of producing enduring classics will be greatly reduced. Moreover, a “Procrustean bed” effect is prevalent in sci-fi readers’ aesthetic preferences—many have relatively conservative tastes that align with “classical science fiction.” They expect works to evoke a sense of wonder, preferably adhering to the narrative traditions of realist literature while incorporating romanticist sentiment, achieving the Aristotelian concept of “catharsis” through the Longinian ideal of the “sublime.” By this standard, Liu Cixin’s “neo-classical” works align most closely with these expectations, whereas more experimental or avant-garde sci-fi often faces marginalization, criticism, or even outright exclusion from the category of science fiction itself.

Reflecting on the development of Chinese science fiction over the past three decades, compared to earlier periods such as the early 20th century or the years immediately following the founding of the PRC, sci-fi has largely shaken off its previously suppressed and passive status, shedding many burdens it was never meant to bear. In a diversified and dynamic economic environment, it has ushered in the fourth major boom in the history of Chinese science fiction. The achievements of contemporary Chinese sci-fi are undeniable, but the challenges it faces should not be overlooked. It is hoped that more professionals will recognize these issues, adopt a long-term perspective, and strive tirelessly for the healthy growth of Chinese science fiction.

Lyu Chao is a professor from the School of Literature at Tianjin Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG