Delving into the blue-green realm in Dunhuang murals

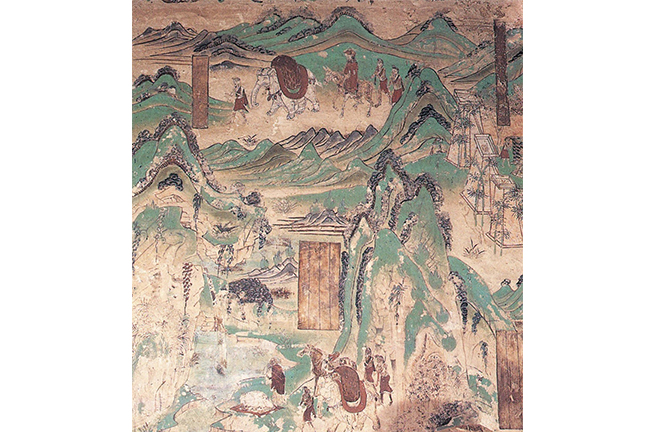

A detail of the mural found in Mogao Cave 103 Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Blue-green landscape painting is an important branch of traditional Chinese landscape art, distinguished by its portrayal of the leisurely, refined lifestyle and ideals of literati. The Dunhuang blue-green landscape style began to take shape during the Wei-Jin period (220–420), developed freely as an alternative art form during the Northern Zhou (557–581), and went mainstream during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). Starting from the Five Dynasties period (907–979), the influence of the Uyghurs led to a notable rise in “green-background” murals [murals of the Thousands Buddhas or Pure Land transformations set against green backgrounds]. The Song Dynasty (960–1276) saw a revival of the blue-green style, but its prominence waned after the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), leaving only a handful masterpieces preserved for posterity.

Early exploration of blue-green art

Early Dunhuang blue-green landscape paintings often incorporated foreign artistic influences while drawing from Central Plains techniques, resulting in vivid and imaginative compositions. From the Northern Wei (439–581) to the Sui Dynasty (581–618), these works retained the narrative and stylistic features of earlier religious-themed paintings—subjects such as mountains and trees were depicted realistically and naturally.

During the Northern Wei period, Dunhuang landscape paintings gained a sense of spatial depth. A notable example is Mogao Cave 257, where the lower part of the south wall features the story “Novice Monk Guards Precepts.” This work employs the “Western Region Blending Technique” [involving applying base flesh tone to a human figure, outlining it with layers of red colors, then gently blending the color within the contour lines, creating a gradient effect]. The triangular mountains in the mural are painted with solid, rich colors such as laterite and mineral green, while the cave ceiling features a row of mountains of varying heights arranged horizontally. These mountains, devoid of trees and smaller than the human figures, serve more as decorative elements.

New techniques emerged during the Western Wei period, introducing more sophisticated depictions of natural features. For instance, some mountain peaks were painted in horizontal layers to capture the interplay of clouds and mist. A prime example is the mural “500 Thieves Become Buddhas” in Cave 285, where jagged peaks are outlined first and then shaded with similar colors, creating an effect of distant mountain ranges. The use of intermediate colors to create smooth gradations between distinct hues on the mountains further evokes the poetic imagery of winding paths leading to secluded places.

During the Northern Zhou era, with the popularity of long-scroll narrative paintings, mountains, rivers, and trees began to appear in various artworks, either as background elements or as scenery separating different story scenes. These works incorporated techniques from south China and the Central Plains, with distant mountains, nearby water, as well as intricate pavilions and towers. Compositions from this period are notable for their grandeur, detail, and smaller human figures, achieving an overall harmonious and realistic effect. In Sui Dynasty murals, a clearer distinction between foreground and background began to emerge, with a stronger emphasis on realism. The “Story of Sudinna” narrative painting in Mogao Cave 423 illustrates this development, with its prominent main and side peaks rendered using an application of blue-green pigments, signaling a stylistic shift during this era.

Advancement in middle and late Dunhuang art

Early Tang Dynasty landscape paintings generally featured fine lines outlining the forms, with softer brushwork and the filling of colors. Figures were usually small, with landscapes dominating the composition, marking a significant shift in the relationship between figures and landscapes from earlier works. This period also saw landscape painting beginning to stand on its own as an independent genre. During the High Tang period, blue-green landscapes used colors like mineral blue and mineral green to achieve blending effects. Painters favored combinations of bright colors, using golden lines for the outlines of mountains, rocks, buildings, and water, creating a luminous, splendorous effect. A representative example is the mural “The Lotus Sutra of Wondrous Dharma,” found in Cave 23. The period between 781 and 847, when Dunhuang was ruled by Tubo, saw a maturation of Dunhuang landscape painting. “Small landscapes” became more common, with simple, soft, and fresh colors. Iconic works like the large mountains depicted in the “Maitreya Triple Sutra Illustration” in Cave 231 and the Dharma preaching scene in Cave 369 evoke the dreamlike essence of the Hexi Corridor’s natural scenery.

From 847 to 1036, when the Hexi region was under the rule of the “Gui-yi Jun” led by Zhang Yichao [who pledged loyalty to the Tang court and was knighted as Commissioner of Hexi in return], a large number of “green-background” murals appeared in the Mogao Caves. After the decline of Cao clan and during the rule of the Shazhou Uyghurs and Western Xia, Dunhuang’s blue-green landscape painting experienced a brief period of stagnation. However, a revival occurred in the Yuan Dynasty, driven by the Yuan people’s appreciation for green and blue and their tendency to “return to tradition,” which aligned with their inclination toward the traditional styles of the Jin and Tang dynasties. Therefore, the development of Dunhuang’s blue-green landscape painting closely paralleled the broader trajectory of Chinese landscape art, yet it retained a distinctive, independent character that reflected the region’s unique cultural and historical context.

Unity of heaven and humanity

The Dunhuang manuscripts contain the philosophical concept of “the unity of heaven and humanity.” An example appears in Kaimeng Yaoxun (Important Instructions for Beginners), which begins with a vivid description of seasonal cycles: Spring flowers bloom brilliantly, summer leaves stretch in splendor, autumn trees shed their leaves, and pine and bamboo remain green in winter. It emphasizes the immutable natural laws governing the seasons, emphasizing that harmony with nature requires adapting to its patterns rather than resisting them. As a children’s primer from the Northern Dynasties, Kaimeng Yaoxun covers various topics but consistently reflects an ecological philosophy that underscores the “the relationship between heaven and humanity.” Other ancient children’s texts found in Dunhuang similarly emphasize reverence for nature and harmonious coexistence with other living beings.

Historical records show that Dunhuang had an arid climate, and was prone to frequent sandstorms. For instance, Dunhuang Han bamboo slip No. 2253 records: “The sun is barely visible, and the black clouds are heavy; the moon is not visible, and the wind (sand) blows.” Recognizing these challenges, the Hexi authorities prioritized the protection of vegetation. Han Dynasty bamboo slips unearthed from the Xuanquan site document detailed forest conservation regulations issued by the Han court in 5 CE. During the Eastern Han period, court official Dou Rong twice issued decrees prohibiting deforestation in the Hexi region. Meanwhile, to ensure effective management of natural water resources, Dunhuang appointed “river stewards” responsible for agricultural irrigation in the counties.

The blue-green landscapes in the Dunhuang murals embody a dual meaning. They depict both the natural landscape and the cultural landscape where humans interact freely with nature. The composition of these natural landscapes largely adheres to traditional Chinese painting conventions, primarily using symmetrical and contrasting arrangements. Mountains may appear in pyramid or circular forms, while rivers take on flowing “Z” or “S” shapes. Such designs express the Confucian aesthetic of “balance and harmony,” the Zen Buddhist conception of imagery, and the Daoist concept of natural law. Together, these influences define the aesthetic pursuit and value of China’s blue-green landscape painting.

Gao Yan is an associate professor from the Dance Academy of Northwest Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG