Stone Age archaeology in Xizang of the past decade

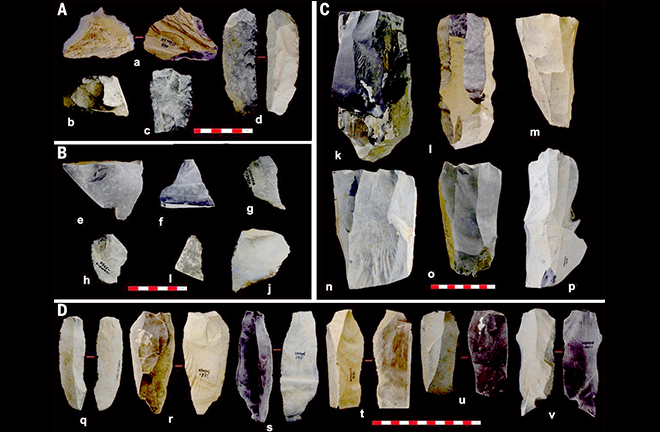

Stone tools unearthed at the site of Nwya Devu, Xizang Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Over the past century, archaeological efforts in China’s Xizang Autonomous Region (hereinafter referred to as Xizang) have yielded significant achievements. In recent years, Xizang archaeology has flourished, with discoveries increasing exponentially, enabling the preliminary reconstruction of Xizang’s archaeological and cultural history from prehistory to the Tubo period (633–842). Chinese scholars from both Han and Xizang backgrounds have collaborated closely, establishing a mature and stable cooperation framework that provides a solid foundation for the sustainable development of archaeological work.

Paleolithic Era

The Paleolithic era was the first focus of archaeological exploration in Xizang following the founding of the PRC in 1949. Yet for nearly half a century, debates over when Xizang entered this epoch were mired in uncertainty, hampered by a dearth of reliable stratigraphic evidence and precise dating. Over the past decade, significant progress has been made, not only resolving this longstanding issue but also continuously updating the earliest known records of human occupation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. These findings have deepened our understanding of ancient human settlement and the long-term habitation processes on the plateau.

Among these revelations, the site of Nwya Devu stands as a crown jewel. Nestled on the northern plateau near Siling Lake at a breathtaking altitude of 4,600 meters, this open-air lithic site represents the earliest known Paleolithic settlement in Xizang with intact stratigraphic layers. From 2016 to 2018, joint excavations by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Xizang Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics Protection uncovered numerous flake tools, suggesting the site was used for early stone tool production. Optically stimulated luminescence dating of the site indicates an age of 40,000 to 30,000 years, resolving the question of Paleolithic chronology in Xizang that had puzzled researchers for decades. The site also yielded Acheulean-like and Levallois tools, providing valuable materials for studying human expansion in western Xizang during the late Pleistocene. The flake tool technology at Nwya Devu shares striking similarities with the Levallois tradition found at the Shuidonggou site in Ningxia and several Siberian sites, both in terms of technique and time period. This connection suggests that lithic flake technology was likely introduced to the region from northern China.

Situated in Gê'gyai County, Ngari Prefecture, the Melong Tagphug cave site holds a unique place in Qinghai-Xizang Plateau archaeology. It is not only the first prehistoric cave site excavated in the region but also the highest-altitude prehistoric cave site in the world, perched at an elevation of approximately 4,700 meters. Between 2018 and 2023, excavations uncovered a remarkable collection of over 10,000 artifacts spanning the Paleolithic to Neolithic periods. These included stone tools, pottery fragments, animal bones, bronzeware, bone implements, and iron tools. The stone tools include lithic cores, microlithic core, microliths, and other tools.

The site consists of three separate caves in a linear arrangement. Carbon-14 dating of the upper strata of Cave No. 1 indicates that human activity at the site dates back to nearly 4,000 years ago. The main cultural layer in Cave No. 2 dates to no later than 45,000 years ago, possibly as early as 80,000 years ago. This site offers key evidence for major scientific questions, including how ancient humans adapted and evolved in extreme high-altitude environments, early human settlement in the plateau’s heartland, the migration routes of early modern humans, and the domestication and utilization of animal and plant resources.

In neighboring areas of Xizang, significant Paleolithic discoveries have also been made, including the excavation of sites such as the Baishiya Karst Cave in Xiahe County, Gansu, the Piluo site in Daocheng, Sichuan, the Dingdu Puba Cave site in Yushu, Qinghai, and the Tangda site in Chindu County. These sites, spanning the late Middle Pleistocene to the Middle Holocene, push the earliest known human activity on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau to 190,000 years ago. These discoveries confirm that Archaic Homo sapiens—Denisovans—inhabited the northeastern plateau for extended periods. Together, they form a continuous chronological framework for hunter-gatherer activity, offering key preliminary insights into their cultural traits, survival strategies, and migration patterns.

In terms of the distribution of remains and cultural traits, new discoveries in the heartland of Xizang further solidify the connection between Paleolithic cultures on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau and northern China. At the same time, the appearance of Acheulean traditions in the eastern plateau raises questions about the eastern migration route of ancient human groups onto the plateau and their potential interactions with the South Asian subcontinent. The appearance of Mousterian Industry traditions in western Xizang also suggests the possibility of an expansion of early plateau settlers from west to east. However, genetic analysis of Neolithic and later populations on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau suggests that the main migration route of early human groups to the plateau seems to be from the northeastern direction, with cultural influences from northern China still playing a dominant role. More cultural factors, rather than direct migration from the South Asian subcontinent, entered from western Xizang. From the broader perspective of human development across the entire Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, the genetic contribution of South Asian populations is extremely small, with closer ties to northern China and the ancient ethnic groups from southwestern China.

This historical trend can be traced back to the Paleolithic era. If Paleolithic populations from the South Asian subcontinent had formed large-scale, seasonal survival patterns on the plateau, there would have been observable traces in the genetic composition of later plateau populations, unless these groups from South Asia had formed a genetic isolation with the plateau’s ancestors for some reason, or were completely wiped out or moved back to lower-altitude regions—the likelihood of such a scenario occurring in the ancient, culturally diverse and continuously evolving Qinghai-Xizang Plateau is low.

Neolithic Era

During the Holocene, high-altitude regions of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau became key centers for microlithic blades and other microlithic tools, originally found in East Asia and Northeast Asia. Around 15,000 years ago, these tools spread from northern China to the plateau, passing through the northeastern edge along the shores of Qinghai Lake, Kunlun Pass, and the Qingnan Plateau [part of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, situated south of the Kunlun Mountains and north of the Tanggula Mountains in Qinghai Province], eventually reaching the plateau’s heartland around 11,000 to 10,000 years ago. Numerous microlithic remains have been discovered along the northern edge of the plateau, at sites such as No. 151, Jiangxigou No. 2, Tongxian, Layihai, Andaqiha, Xidatan, Yeniaogou, Xiadawu, and Canxionggahuo. Excavations have revealed large quantities of stone tools, wild animal bones, evidence of fire use, charred plant foods, and occasionally pottery fragments, with dates ranging from 13,000 to 6,000 years ago, at altitudes between 2,500 and 4,560 meters. The technological characteristics of the stone tools are closely related to the “Yangyuan technique” [a type of Late Paleolithic stone tool manufacturing technique discovered at Yangyuan County, Hebei Province, characterized by the use of wedge-shaped microlithic cores to pressure-flake small microlithic blades] and “Layihai technology” [a microlithic manufacturing technique from the Mesolithic period, named after the characteristics of stone tool production found at the Layihai site at Guinan County, Qinghai Province] found in North China and the upper reaches of the Yellow River. These remains are typically associated with temporary camps of small hunting groups during the late Pleistocene.

The distribution of microlithic remains in Xizang is much more widespread and extended over a long period, ranging from around 11,000 to 3,000 years ago. Despite the discovery of many new microlithic blade technology sites, with 40 reported sites in northern Xizang, most are surface collections, and only a few have been reliably dated. Section No. 3 of Nwya Devu yielded over 1,100 stone tools, mainly microlithic blades, dating to 11,000 to 10,000 years ago, making it the earliest microlithic blade site found in the heartland of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. The Siling LD site revealed numerous microlithic blade products, a small amount of coarse sand pottery, and animal remains, dating from 6,800 to 400 years ago. It is the earliest known site with clearly stratified deposits and continuous evidence of human activity in northern Xizang, spanning the Middle Holocene to the present.

Sites discovered in western Xizang include the microblade sites north of Drongpa County, Dingzhong Huzhuzi microlithic site in Gar County, and Xiaqulong site at Rutog County, most of which are surface collections without stratigraphic relationships or specific dating. The Yali site, discovered on the northern slope of the Himalayas in Nyalam County, Shigatse, Xizang, is believed to be over 3,800 years old based on carbon dating of ashes collected from nearby pit samples. In the middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River near the Lhasa River and the western Sichuan-eastern Xizang region, microliths and pottery fragments are often found together. The majority of these date back to 5,500–3,500 years ago, marking the transition into the typical Neolithic period.

These discoveries illustrate the gradual spread of microlithic blade technology from northern China to the entire Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Around 5,500 years ago, cultural elements such as pottery, agriculture, and settlements began to appear on the plateau. The distribution of microlithic blade populations gradually contracted to the mountain valleys or basins in southern and eastern Xizang. Molecular biological studies indicate that the large-scale migrations of microlithic blade populations coincided with major human migrations to the plateau in the Early Holocene. After migrating to the plateau, these groups did not disappear or get completely replaced; instead, they persisted and evolved on the plateau, potentially forming the core ancestral population of modern Xizang.

In recent years, Neolithic archaeological discoveries in Xizang have seen significant breakthroughs, particularly at sites like Mabucuo, Xiadacuo, and Bangga. Notably, the process of Neolithic human settlement on the plateau has become a focal point of academic attention. Archaeological surveys of the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau have led to a series of preliminary conclusions: around 15,000 years ago, microlithic-blade-using groups entered the northeastern plateau region near Qinghai Lake; by around 9,000 years ago, hunter-gatherer groups that had previously roamed at altitudes of around 3,000 meters entered the central plateau regions at altitudes of around 4,000 meters; around 5,200 years ago, millet-farming agricultural populations from the Loess Plateau spread to and settled in the river valleys below 2,500 meters in the northeastern Qinghai-Xizang Plateau; around 3,600 years ago, the development of wheat agriculture prompted prehistorical humans to settle at altitudes above 3,000 meters.

Recent genetic studies suggest that Tibeto-Burman populations share a common ancestor with the Mongoloid populations of Asia. Modern Xizang trace their origins to millet-farming agricultural groups from the Yangshao and Majiayao cultures that emerged in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River of China around 6,000 years ago. Around 2,800 years ago, these populations began spreading to high-altitude areas such as Nepal from the regions centered around the Zongri site in the upper reaches of the Yellow River. Of course, the contemporary Xizang population also incorporates other maternal genetic components, possibly linked to high-altitude populations that existed earlier on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau.

Tong Tao is a research fellow from the Institute of Archaeology at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG