Pan Guangdan’s fascination with antique treasures

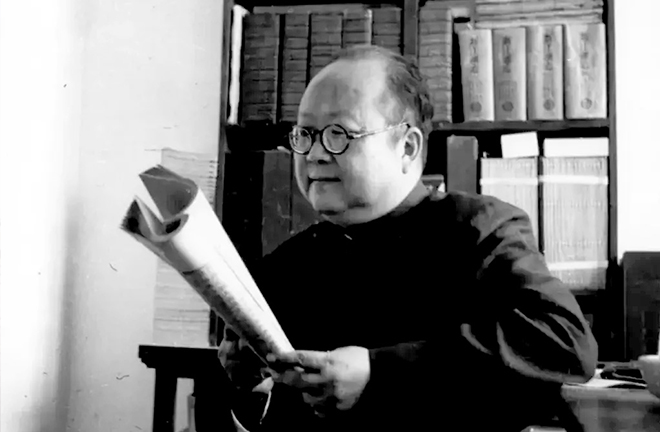

FILE PHOTO: Pan Guangdan is widely recognized as China’s pioneering sociobiologist.

Professor Pan Guangdan of Tsinghua University spent the first three days of 1947 at an antique market in southern Beijing. On New Year’s Day, he and his friend, Professor Chen Futian from the English Department, visited the antique market at Xiagongfu south of Wangfujing to purchase a mahogany plate stand and a small square box inlaid with jade. Pan’s diaries from 1947 to 1950 frequently mention his fascination with appreciating and collecting antiques. This passion was an important aspect of his life beyond academics. Pan had a keen interest in antiques and considerable appreciation skills, as reflected in his diaries filled with notes on his collection of inscriptions, books, paintings, calligraphy, along with bamboo, wood, and ivory artifacts. The renowned writer Bing Xin once claimed that Pan exemplified the perfect balance between sense and sensibility among the men [that she knew]. However, Pan’s diaries reveal that his passion for antiquities occasionally tipped toward indulgent obsession, deviating from his usual restraint.

Antiquarian interest

In the Chinese literary tradition, antiques were often seen as “external attachments,” yet their enjoyment and appreciation played a significant role in the literati lifestyle. This tradition began to wane in the early 20th century with the abolition of the imperial examination system and the disintegration of the traditional literati class. Surprisingly, despite his exposure to Western ideas and his experience as an intellectual returning from overseas, Pan retained this antiquarian interest typical of traditional Chinese scholars.

Pan’s collections mainly fell into three categories: genealogies, calligraphy and paintings, and scholarly tools and furniture. Though interested in calligraphy and paintings, he was most captivated by scholarly tools and classical furniture. In recent decades, Ming-style furniture made from Chinese rosewood and red sandalwood has become a new favorite in the collecting community. Pan’s diaries recount encounters with wooden pieces like Chinese rosewood cabinets and red sandalwood square tables, which he occasionally purchased if the price was fair. For example, his diary from November 18, 1949, notes a visit to the Dongdan market where he spent three hours browsing before buying a small red sandalwood table for 4,000 yuan. However, Pan did not view these items as part of a formal collection; rather, he saw them as practical objects for study, as he was not particular about materials. One year he even retrieved a large cypress root from the roadside at Tsinghua University and had carvers fashion it into a round chair under his direction.

Growing up under the influence of the May Fourth Movement, Pan belonged to a generation characterized by a paradoxical attitude toward tradition, described by Joseph Richmond Levenson as “straining against his tradition intellectually, seeing value elsewhere, but still emotionally tied to it, held by his history.” Yet, Pan’s relationship with antiques was about more than mere emotional affinity; he possessed a comprehensive understanding and appreciation system. His longstanding emphasis on the importance of antiques is evident from a 1930 essay titled “Chinese People and Studies of Ancient Chinese Civilization,” in which he lamented the ongoing looting of China’s valuable antiques and expressed concern over the loss of cultural heritage, fearing that future generations would have to go abroad to study their own cultural relics. In 1947, while serving as librarian of Tsinghua University Library, he noticed a decline in private book collections in Jiangnan, in south China, as many families had, for various reasons, sold their multi-generational collections. He attributed this trend to the enduring disdain for old artifacts since the May Fourth Movement.

'Preserving humanity'

So, what exactly did Pan enjoy about antiquities? As the only scholar in the sociological field focused on Confucian social theory and its modernization at the time, Pan’s appreciation of antiques formed a crucial part of his inner world. For Pan, antiques represented the essence of national culture and spiritual tradition, symbolizing the classical civilization he cherished. He believed that understanding one’s cultural history could provide solace in times of crisis.

Pan’s antiquarian pursuits transcended mere aesthetic appreciation, subtly connecting with his scholarly thoughts and writings, particularly his academic ideal of “preserving humanity.” Drawing on Fei Xiaotong’s words, Pan’s appreciation of antiques can be seen as a form of “cultural awareness.” The enduring artifacts of literati culture are deeply infused with Confucian values, becoming part of the “humanistic world.” Throughout his life, Pan’s fundamental concern was to forge new possibilities for Confucian civilization in the modern era. The cultural continuity represented by these artifacts needs to be preserved through the creation of a new humanistic world.

Wen Xiang is a professor from the School of Social Research at Renmin University of China.

Edited by REN GUANHONG