Han portraits put face on history

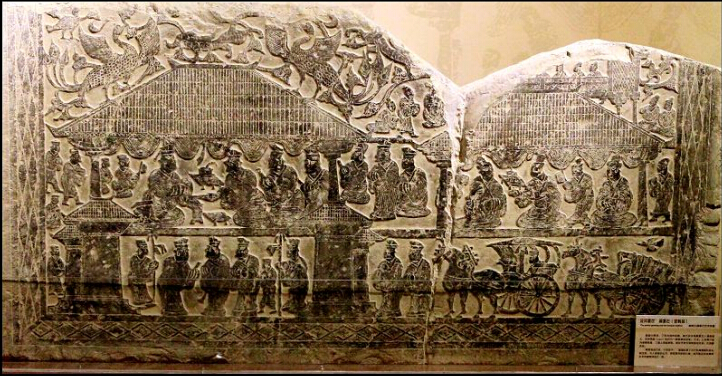

Han portraits offer an abundant, accurate and complete picture of life in the Han Dynasty. This is a piece of Han portrait preserved in the Three Gorges Museum./file

Combining realism with emotion, Han portraits depicted a unique and complete spiritual structure. It is a product of people living during the Han Dynasty, who drew upon mythological images to immortalize scenes of ordinary life.

It is astonishing that Han portrait painting emphasized the mundane. Han portraits offer an abundant, accurate and complete picture of life in the Han Dynasty. These depictions of life and entertainment, production, becoming an official, going to the court, hunting, and fighting in war can be looked at as serious research materials.

The paintings provide a window into the social life of that period, playing an irreplaceable role in vividly recreating the era. Obviously, when Han people created these pictures, they did not view them as fantasy but adopted an attitude called “complete realism.” These fine, lifelike depictions of ordinary life allow the viewer to experience the inner world behind the Han portrait, and in return the inner world can enhance people’s recognition of the joys of mundane life.

“The joy of man’s life” is a core topic of the aesthetics of Han portraits. This theme was essential. Not only did it affect Chinese people’s understanding toward life and existence but it was also reflected in their tombs.

The carving stone excavated in Yinan, Shandong province, is one example, it vividly, accurately and completely recorded a lively picture of the couple buried under the tomb having meals, showing the servants’ preparations before each.

The Yinan stone only revealed one scene of life for Han people. Many other similar Han artifacts demonstrated that Han people not only preserved different scenes of their lives as pictures but also buried all kinds of goods in a pattern of symbols or real objects in tombs. Apparently, this pattern has gradually developed into a normative and compulsory custom during the period of two Han Dynasties (especially the Eastern Han Dynasty).

Wang Huaiyi is from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Jiangsu Normal University.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 657, Oct. 17, 2014

Translated by Zhang Mengying

The Chinese link:

http://sscp.cssn.cn/xkpd/ysx_20173/201410/t20141017_1366507.html