Chinese identity extends from self to family, nation, and world

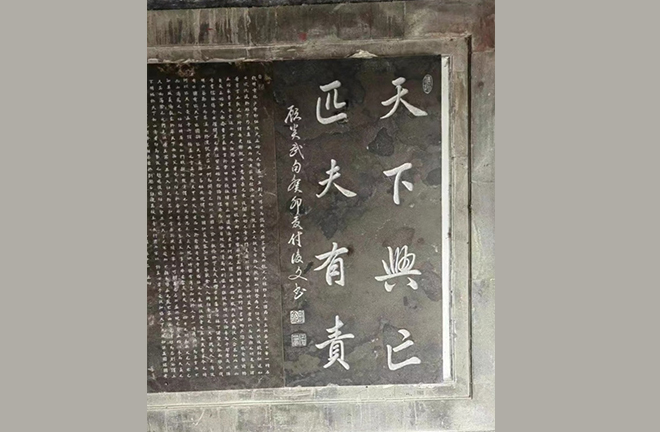

FILE PHOTO: A tablet inscription, titled “The Survival of a Nation is the Responsibility of Every Individual,” at the Baoguo Temple in Xicheng District, Beijing

The building of a human community with a shared future, a significant part of Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy, is deeply rooted in the soil of Chinese civilization, reflecting cultural confidence and a global vision. “Jia guo tianxia,” literarily “family, nation, and all under heaven,” has been a cultural mindset and meaning system through which the Chinese deal with individuals’ relationships with their families, the nation, and all under heaven, or the world, since antiquity. This concept has been imprinted in the mind of every Chinese.

As a psychological resource for fine traditional Chinese culture, jia guo tianxia has provided soil and nourishment of “re-embedding” for modern Chinese people to cope with the crisis of dis-embedding from the “self-family-nation-world” continuum. Advancing human progress and the world’s peaceful development by building a human community with a shared future requires every modern Chinese to construct their global identity based on the jia guo tianxia philosophy.

Organic continuum

Chinese people’s concept of the self differs from Western individualism that antagonizes the self against society. In Chinese culture, individuals are interconnected to others and society, prioritizing their families and the nation over the self. From the perspective of cultural psychology, jia guo tianxia is an organic continuum in the self-concept of Chinese people.

According to the theory of chaxu geju (differential mode of association) put forward by renowned Chinese anthropologist Fei Xiaotong, the self-concept of Chinese people is an expandable organic continuum stretching from the self to one’s relatives, acquaintances, the workplace, communities, society, even to the nation and the world. Therefore, a typical Chinese person will, first, not regard himself or herself as an individual independent from the outside, but as a node in a social network, assuming one or multiple role(s) in different situations amid interdependent ties with others and society.

When individual interests conflict with interests of others, those of a broader collective, or society, the Chinese are apt to expand their self-identity from an individual level to broader social relations, such as family, the nation, and even the world, instead of sacrificing others’ interests in a self-centered fashion. Through the lens of modern cultural psychology, the self of Chinese people is collectivist and interdependent, while the Western self is individualistic and independent.

A wealth of research projects on self-image, which address the classic philosophical question “Who am I?,” reveals that Westerners with an independent self-orientation are inclined to describe themselves through their own abilities, interests, and personal qualities, while the Chinese, who regard themselves as interdependent, tend to refer to their social roles in self-description.

As modernization and globalization intensify, particularly as China has undergone dramatic societal and cultural changes since reform and opening up, many studies have observed a rising individualism and independent self among the Chinese. Does this signify a rupture in Chinese people’s family-nation-world continuum?

Cultural psychologist Zhu Ying, through several cognitive psychology and cultural neurology studies, found that modern Chinese people’s self-concept still contains an attachment to the mother. When the Chinese memorize adjectives, it activates a mother-reference effect that is seldom observed among Western people. Moreover, the area of the brain associated with this effect is the same region related to their self-concept. This suggests that modern Chinese people’s self-concept remains unchanged despite modernization and cultural shifts. They are still not independent selves irrelevant to others. In Chinese culture, mothers symbolize family, and the concept of jiaguo tonggou, which means the family is a reduction of the nation and the nation is an amplification of the family, indicates that the Chinese’s self-concept is characterized by a family-nation sentiment.

Pursuing harmony

In Chinese people’s family-nation-world continuum, there is a long distance from the self to the world, covering groups of multiple levels in the middle. Traditionally, the Chinese span from the self to the world through self-cultivation, progressing from one level to the next.

Throughout history, the importance of “cultivating oneself, regulating families, governing the state properly, and ensuring peace to all under heaven” has been reiterated. By logical extension, personal moral cultivation is consistent with bringing order to the state and peace to the world. It requires steady progress from near to far, from oneself to others, and from micro to macro. In this process, oneself and social groups, the self and others, and individuals and communities are always organically connected. This organic connection reflects Chinese people’s relational mentality.

Western people, in contrast, normally view social relations from an analytical perspective. Western modern social psychology separates the self from others and individuals from groups. Phenomena in social psychology are understood discretely from different explanatory levels, such as individuals, interpersonal relations, intra-group interactions, inter-group communication, and macro ideologies. In this analytical framework, the vast range of social relations—from the self to the world—would be divided by impenetrable and either-or biological, societal, and cultural labels, laden with isolation, conflict, and fighting between groups.

From the Chinese cultural perspective, people prefer to adopt a relational approach within the family-nation-world continuum, seeking harmonious intergroup relations and holding a constructivist outlook. Conversely, Westerners resort to an analytical thinking pattern, handling intergroup relations with a latent propensity for eliminating differences by excluding dissent. They hold an essentialist view of isolation and conflict.

The Chinese don’t classify and view social groups by biological attributes such as gender and race. Instead, they expect all groups to seek common ground while reserving differences and coexist harmoniously on the cultural and social fronts, thereby fostering interdependent organic relationships amid long-term interactions and exchanges. The formation of the Chinese nation’s unity in diversity ethos is fully reflective of Chinese people’s mental orientation, which pursues harmony in inter-group relations.

China’s recent call to foster a strong sense of community for the Chinese nation encourages all ethnic groups to embrace each other closely “like pomegranate seeds.” This aligns with its vision of building a human community with a shared future and advancing exchanges and mutual learning among different civilizations worldwide. Together, they represent a major innovation in Chinese people’s cultural inclination toward harmonious group relations.

Advocating for universal wellbeing

In Chinese people’s family-nation-world continuum, from inside to outside and from the self to society, the outermost identity is an association with the world or humanity. A global identity seems distant from the self, but it remains within the continuum, the core of which is the individual self.

In Chinese people’s relational mentality, the world is a concrete, approachable object everyone can be associated and interacted with. For example, Zhu Ying and Wu Xihong, another cultural psychologist, noted that when answering the question “who am I?,” the Chinese often reply: “I am human.” This reply doesn’t mean “I am [simply] a member of human society.” It marks the relational idea that “I am human among all beings in heaven and earth [the universe].”

The entire family-nation-world continuum essentially stresses internal and external harmony of individuals, harmony between the self and others as well as society, and harmony between different groups. It is a holistic framework characterized by animism including the harmony between humanity and all beings in nature, and equality between the self and others, conveying a value orientation best described as transcendental universal harmony for world order.

On the contrary, in the Western analytical framework, a person’s world identity exists in dualistic comparisons within each social category, such as the human and the non-human, which can easily give rise to anthropocentrism. Therefore, Western worldviews always focus on the self and non-self, the center and the periphery, and dominance and subordination.

Since ancient times, the Chinese have valued harmony and peace. The Chinese nation has never proactively launched aggressions against other nations or states. From the perspective of cultural psychology, Chinese people are prone to exercising forbearance when confronted with conflict and hold a relatively optimistic and peaceful life attitude. On a macro level, these factors are manifested in national strategies, and microscopically, penetrate everyday life of Chinese people.

First, in the family-nation-world continuum, the self of Chinese people is by no means a determinist existence. Instead, it emphasizes growing from a smaller self into a broader-minded and more virtuous greater self through self-cultivation and self-improvement.

Second, the Chinese never dichotomize the self and others, but think dialectically, as they believe in the constant conversion between yin and yang. Facing conflict, instead of battling it out, they behave with restraint to avoid head-on confrontation, while waiting for opportunities to turn the situation around, selecting countermeasures flexibly. This mindset enables the organic integration of social relations and groups of all levels in the family-nation-world continuum.

Third, the Chinese value relationships, and tend to keep a low profile and seek inner peace in the pursuit of happiness, rather than pursuing enjoyment, excitement, and personal achievements. This value system, when extended to the far end of the family-nation-world continuum, can easily develop into an emphasis on values and notions that are conducive to the building of a human community with a shared future, such as ecological civilization and the sustainable development of humanity, in addition to pacifism.

In summary, the philosophy of jia guo tianxia contains the cultural code for the Chinese to view their relations with society, and the cultural mechanism of their world identity. As an important component of fine traditional Chinese culture, this concept should be creatively transformed and innovatively developed based on China’s current realities and global dynamics.

Wei Qingwang is an associate professor of psychology at Renmin University of China.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG