Translation as a catalyst for China’s knowledge system development

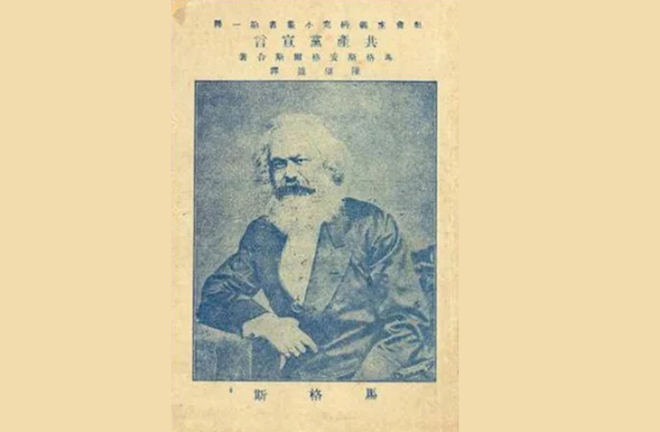

FILE PHOTO: The Communist Manifesto, first translated into Chinese by Chinese scholar and educator Chen Wangdao

From the late Qing Dynasty onwards, the modern Western knowledge system began to reach China via various channels, particularly through translation efforts. Around the time of the First Opium War, Chinese politician Lin Zexu and other insightful individuals began to translate Western books to introduce Western knowledge to China. Over the past century, the translation and publication of books in various fields have been instrumental in building China’s modern knowledge system, demonstrating the nation’s progress in this regard.

A century of evolution

Around the May Fourth Movement, Marxist literature began to be extensively translated in China. The Communist Manifesto, first translated into Chinese by Chinese scholar and educator Chen Wangdao and published in 1920, served as the compass for China’s revolutions. From 1920 to 1948, over 400 Marxist works were translated, accounting for about half of all Marxist works in China. From 1949 to the late 1960s, over 1,000 works were translated, accounting for roughly 30% of all Marxist literature. From the 1970s to 2017, fewer Marxist works were translated, with an annual average of 15, and translated works annually accounted for 6.5% of all Marxist works on average. This trend suggests that since the 1970’s, China’s Marxist knowledge system increasingly has been shifting its focus towards independent innovation.

Few philosophical works were translated into Chinese prior to the May Fourth Movement. The visits of John Dewey and Bertrand Russell in 1919 and 1920, respectively, significantly boosted the translation and dissemination of Western philosophy in China. From 1912 to 1948, over 800 philosophical works were translated, accounting for about 25% of philosophical books in China. By the late 1980s, over 200 works were being translated annually. From 2000 to 2017, nearly 13,000 works were translated, accounting for 17.7% of all philosophical books. After more than a century, translated content still makes up a relatively high proportion of China’s philosophical knowledge system.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, China began to place greater emphasis on the translation of social science books. From 1912 to 1948, over 5,000 social science works were translated, accounting for 6.8% of all social science books in China. By 1977, more than 9,000 works were translated, with the number reaching upwards of 17,000 by the end of the 20th century. From 2000 to 2017, around 68,000 works were translated, accounting for 4.7% of social science books. In China, social science works comprise a small proportion of translations primarily because a significant portion of social science literature consists of indigenous knowledge, such as Chinese history, which is rarely translated.

The translation of natural science works into Chinese can be traced back to 1607 with Euclid’s Elements. Chinese translations concentrated on the fields of applied science such as military technology and manufacturing during the Self-Strengthening Movement. After the First Sino-Japanese War, greater emphasis was placed on the translation of basic research. From 1912 to 1948, over 900 works on basic science and over 800 applied science works were translated, respectively accounting for 25.7% and 8.3% of all basic science books and all applied science books in China.

By the time of the reform and opening up, the numbers of translations in basic and applied science had exceeded 4,000 and 15,000 respectively, with their proportions reaching 29.8% and 19.3%. By the end of the 20th century, while the numbers of both categories of translations were similar to the previous period, their proportions respectively decreased to 13.2% and 8%, which further dropped to 7.4% and 5.4% in 2017.

The decrease in the proportion of translated content in China’s natural science knowledge system, particularly in the fields of applied science, is closely related to China’s modernization. Over the past century, China has developed from a poor and weak semi-colonial, semi-feudal society into the world’s second-largest economy, and has risen to the rank of a world leader in several fields of science and technology.

Independent knowledge system

The evolution of book translation in China can provide insights for the construction of China’s independent knowledge system. Two principles should be adhered to when translating and learning from the achievements of other countries.

The first principle involves seeking the truth, meaning that borrowed ideas must withstand the test of practice and align with China’s reality. It has been demonstrated that many Western analytical frameworks do not necessarily align with China’s reality. The second principle pertains to independence. Knowledge is both strength and power. To preserve China’s discourse power and autonomy, its knowledge and technology systems should not subordinate themselves to those of other countries when assimilating foreign knowledge and technology.

If the 20th century was a century of translation, imitation, and catch-up for China, the 21st century will be a century of independence, originality, and leadership. As more pioneering research is conducted in China and written in Chinese, the Chinese language and culture will also “go global,” contributing Chinese wisdom to the human knowledge system.

Deng Jinlei is an associate professor from the College of Foreign Languages at Fujian Normal University.

Edited by WANG YOURAN