Ancient China-West exchanges advanced human progress

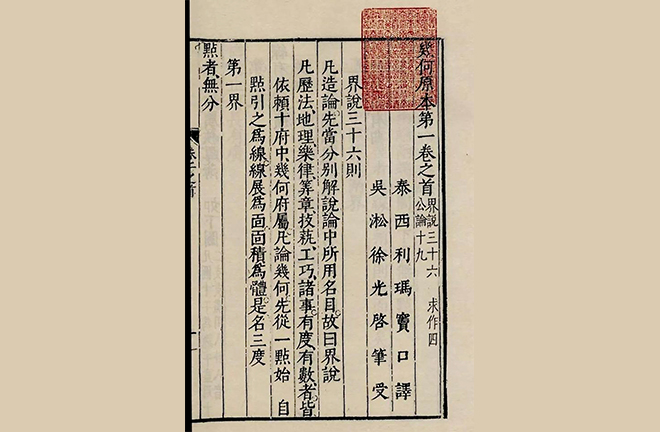

FILE PHOTO: An excerpt of the Chinese translation of the European mathematical masterwork Euclid’s Elements, jointly produced by Xu Guangqi and Matteo Ricci

Based on fossils and archaeological relics, paleoanthropologists trace human ancestry to Africa. They believe that ancestors of modern humans stepped into Eurasia from Africa in the Homo habilis and Homo ergaster stages, roughly 2 to 1.8 million years ago, 840,000 to 420,000 years ago, and 80,000 to 70,000 years ago.

Chinese paleoanthropologists put forward a different hypothesis—“continuity with hybridization,” arguing that the direct ancestors of Chinese people today are Peking Men, dating hundreds of thousands of years ago; while the main lineage stems from Peking Men, some descendants hybridized with other ethnic groups to comprise secondary lineages. In other words, human civilization and evolution had already been marked by each group maintaining their own features while exchanging with others in the initial stage.

Origins of Eurasian civilization

After humans entered the civilized era, including the Chalcolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages, they became considerably more mobile. Indo-Europeans, most typically, transitioned from hunting to nomadism after inventing and proficiently using chariots, which resulted in their massive migration for more than 1,000 years.

This migration wave spread widely, from the Indus Valley to the island of Britain, leading the entire western part of Eurasia, even North Africa to the south of the Mediterranean, to usher in a civilized age of using both copper and stone ware. Against this backdrop, such civilizations as Veda, Persia, Anatolia, and Ancient Greece emerged. In eastern Eurasia, Scythian nomads in northwestern China during the Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Zhou (1046–256 BCE) dynasties and the Yuezhi people who inhabited the Hexi Corridor during the Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (206 BCE–220 CE) were also migrant tribes consisting of Indo-Europeans.

At the same time, the Chinese civilization gradually bloomed, growing along its own unique trajectory. Arguably, Europe was a migratory and transplanted civilization from its start, while Chinese civilization was aboriginal. Western Eurasia and North Africa set a natural stage for civilizational exchanges around the Mediterranean. As a whole, they formed a “Western world” to China. The grandest-scale globalization before modern times was exactly fueled by the overland and maritime Silk Roads which linked China and the Western world.

Exchanges between ancient China and the West evolved over time. Early exchanges took place before Zhang Qian, a renowned Han-Dynasty diplomatic envoy who opened the ancient Silk Roads, a watershed moment in history. The period from Zhang Qian to Zheng He, a prestigious Ming-Dynasty (1368–1644) maritime explorer, was characterized by increased interactions between China and countries in Central Asia, South Asia, and West Asia. From the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty to the 18th century, China primarily communicated with European countries.

Early exchanges

During the period of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, particularly prior to the Shang and Zhou dynasties, Chinese history was supported by legends and archaeological discoveries. Bronzes and chariot pits uncovered from the Yinxu Site in Anyang, Henan Province, and artifacts with West Asian features from the Sanxingdui Site in Sichuan Province were both indicative of early exchanges between China and the West.

In the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770–256 BCE), an era of constant warfare among various states, the states of Qin, Zhao, and Yan, which built the Great Wall in the borderlands, played a leading role in China-West interactions. Duke Mu of Qin expanded China’s territory to the west, laying a solid foundation for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty to later open the Hexi Corridor. Crossing the Great Wall, the State of Zhao communicated with the Western Regions via the Steppe Road and became a hub for distributing luxuries from those regions. Although the State of Yan was faced with threats from the Shanrong ethnic group, a branch of Xiongnu, and Donghu people, it still influenced the Western Regions and vice versa via the Steppe Road.

In 1983, a number of bronze artifacts were discovered in the valley of the Gongnaisi River in Xinyuan County, Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, dating to the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE, before Zhang Qian started his expedition to the Western Regions. Among these artifacts, a bronze warrior statue wears a Greek-style helmet, with the top of the helmet flaring like a cockscomb. He bends over, his right leg kneeling and left leg squatting. The warrior gazes into the distance, with his left hand on his knee and right hand by his thigh. His hands seem to have held weapons, perhaps a bow and arrow or knife and spear. Some scholars argue that this is a representation of the war god Ares in Greek mythology. Despite a lack of documentation, archaeology has provided ample evidence of early East-West exchanges.

Interactions in middle ancient times

From Zhang Qian to Zheng He, and from land to sea routes, official expeditions were launched from time to time. These official and non-governmental political, diplomatic, and trade exchanges involved communication and clash on institutional, cultural, material, intellectual, and many other levels.

China-West relations during the Han and Tang (618–907) dynasties, after Zhang Qian ventured to the Western Regions, promoted exchanges of envoys and merchants from China and countries in the Western regions, trade of animal and plant products, and dissemination of thought. A Xuanquan bamboo slip of the Han Dynasty found in Dunhuang, Gansu Province, carries the Chinese characters “浮屠” (futu, meaning Buddha, monks, or pagodas), implying the introduction of Buddhism to China at the time.

Nonetheless, Buddhism and three other exotic religions—Zoroastrianism, Nestorianism, and Manicheism—were widely spread and accepted in the hinterlands of China not only because merchants and monks from the Western Regions excelled at interacting with China, but also because political divisions during the Han and Tang provided opportunities for the dissemination of these foreign religions. Artistic and religious elements of the Western Regions, discovered in the tombs of Northern-Dynasty (439–581) diplomat Yu Hong, as well as Shi Jun and An Jia from the Northern Zhou era (557–581), offered new archaeological evidence.

Communication between the Tang Empire and the Western Regions further broadened China-West exchanges in the Northern Dynasty. The lifestyle of Sogdians, who came to China from Central Asia, was gradually assimilated in the Central Plains. In the late 8th century, the Tang court dispatched official envoy Yang Liangyao to the Arab Empire, which filled the void of official exchanges on the maritime Silk Road during the Han and Tang dynasties.

In 1998, a shipwreck was discovered off the coast of Belitung Island, Indonesia. It contained a cargo of Chinese commodities to be transported to West Asia and North Africa, with the number of porcelain objects produced in the Tang Dynasty totaling 67,000, alongside lots of gold and silver ware and bronze mirrors.

Exchanges on the Silk Roads during the Tang and Han times featured overland trade of silk, while the Song (960–1279) and Ming dynasties mainly saw porcelain traded via maritime routes. Nonetheless, during the Song and Ming, two achievements are noteworthy. First, the Western Liao regime (1124–1218), led by the Khitan Mongols, entrenched its rule in Central Asia, expanding the influence of Chinese culture to the Western world. This regime was so influential that the West referred to China as “Cathay,” based on the Mongol term “Khitai.” Second, ceramic manufacturing as well as compass, printing, and gunpowder technology was shared with the West, triggering a technological revolution worldwide.

Early modern times

The period from Emperor Wanli in the late Ming Dynasty to Emperor Qianlong in the early Qing (1644–1911), approximately from the 15th to 18th centuries, constituted the first 300 years of the West’s foreign expansion, and can be regarded as the early modern times. During this period, regionally, China maintained frequent exchanges with Asian countries, but its interactions with Europe were most remarkable.

At the time, China was still an independent sovereign state politically, different from its nature as a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society after the mid-19th century. In economic terms, China and the West conducted trade exchanges largely on a voluntary basis. Although China gradually fell behind in economy and science, the eastward transmission of Western culture and the spread of Chinese culture to the West remained on a reciprocal and equal footing.

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Jesuits played the principal role in cultural communication between China and the West. They not only profoundly influenced Chinese people’s understanding of Christianity, but also deeply changed Europeans’ perceptions of China. The overall image of China, shaped by Jesuits, became the starting point for Europeans to make sense of the Eastern nation, and the foundation for them to imagine a “China” in their minds.

As one of the first missionaries to China, Italian Matteo Ricci not only disseminated Western knowledge, but also attempted to introduce Chinese classics such as The Analects back to Europe. He maintained good relationships with Chinese scholar-officials and translated the European mathematical masterwork Euclid’s Elements together with famed Ming-Dynasty scientist, politician, and scholar Xu Guangqi, marking the first time a Western science text was rendered into Chinese. Later, Xu co-translated other Western books including the Hydromethods of the Great West with Italian Jesuit Sabatino de Ursis. Moreover, Xu’s magus opus of agronomy Nongzheng Quanshu, or Complete Treatise on Agriculture, crystallized the quintessence of ancient Chinese agricultural technology, and incorporated Western science expertise.

Additionally, German Jesuit Johann Adam Schall von Bell, who used to serve the Imperial Board of Astronomy in the Ming Dynasty, dedicated the Chongzhen Calendar, which he compiled in collaboration with Xu Guangqi and Li Tianjin, to Emperor Shunzhi of the Qing Dynasty and was appointed to a high-ranking position.

During the reign of Emperor Kangxi, many Western missionaries came to China. The emperor even wrote to King Louis XIV of France, expressing the hope that more missionaries could be sent to China to spread Western learning. Emperor Kangxi himself also learned to make astronomical instruments, studying geometry and algebra. He even founded a school for children of the imperial family to study science.

Generally, Chinese culture’s influence on the West and the dissemination of Western culture in China reached unprecedented heights, peaking from the 16th to mid-18th century.

Now nearly one quarter of the 21st century has passed. History continues to remind us of the great importance of intensifying exchanges and mutual learning between civilizations, seeking commonalities while reserving differences, and collaborating to tackle intricate challenges, amid profound changes unseen in a century across the world.

Zhang Guogang is a senior professor of liberal arts at Tsinghua University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG