The epic journey of China’s Red Army

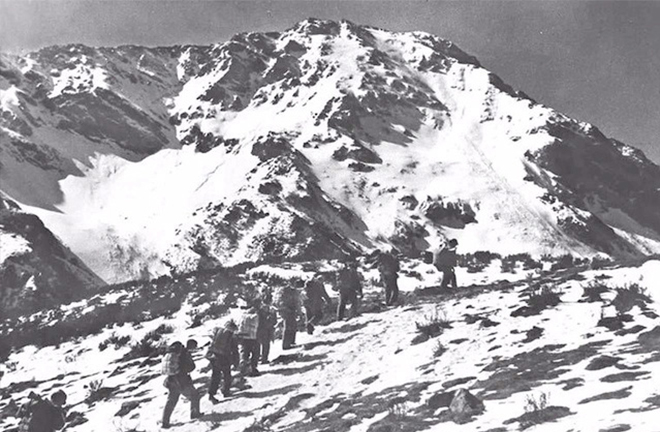

FILE PHOTO: Red Army soldiers marching on the snow-capped Jiajin Mountain, Sichuan, in 1935

Notes on Retracing the Long March is a book delving into the historic Long March undertaken by the Red Army under the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in the 1930s. Authored by Wei Yonggang, a senior editor of the Economic Daily, it serves as a testament to his emotional journey while retracing the footsteps of the Long March. In 2019, Wei dedicated over a year following the route of the Red Army, unearthing their narratives and vividly recounting the grandeur of this remarkable expedition.

Untold stories

Wei spent more than a year traveling through provinces including Jiangxi, Hunan, northern Guangdong, Guizhou, Sichuan, Gansu, and Shaanxi. He engaged with locals along the way and particularly focused on the descendants of the Red Army, meticulously documenting numerous anecdotes from the Long March.

In Xinfeng County, Jiangxi Province, Wei stumbled upon the final resting place of Hong Chao, the first division commander who died during the Long March. Recollections from local village officials vividly depicted the circumstances surrounding Hong’s demise. Struck in the head by a stray bullet while reconnoitering the enemy frontline, he succumbed to his injuries while departing from the Central Revolutionary Base [also known as the Central Soviet Area, centered around Ruijin county in Jiangxi Province, mostly covers areas in present-day southern Jiangxi, western Fujian and northeastern Guangdong provinces].

In Taiping Town, Sichuan, Wei encountered Hu Jinghua, who recounted the tale of his father, a Red Army soldier. Despite facing adversity while recuperating from injury in the local area, he never spent the three silver coins provided to him by the army, symbolizing his unwavering dedication to the cause. In a Dong autonomous county in Guizhou, Yang Changbin, an old man in his 90s, told the touching story of Red Army soldier Qiu Xianda. Following Qiu’s injury, he found refuge in the embrace of the Yang family. Upon recuperating, Qiu set out to reunite with his troops. Before leaving, he crafted two bamboo baskets for the Yang family to express his gratitude. Young Yang Changbin sent his “brother Qiu Xianda” out of the village and bid him farewell. In the years that followed, the Yang family diligently inquired about Qiu, but found themselves bereft of any new information.

More than eight decades have passed since the triumphant conclusion of the Long March. While certain accounts may elude written documentation, they endure through the ages, preserved orally from generation to generation, remaining vivid in people’s memory. Notes on Retracing the Long March re-presents the heroic past of the Red Army soldiers by recording the oral stories told by locals along the route of the historic march. Of those young soldiers, some successfully completed the entire expedition, some were taken in by locals after being injured, and some died in battles. Lan Lao’er was a Red Army soldier whose story has been etched into the collective memory of Kongshuyan, Guangxi, for decades. Separated from his comrades during the retreat, Lan found refuge among local villagers. Embracing his newfound community, Lan became known for his unwavering willingness to assist those in need. One day, Lan was swept away by a torrential flood while trying to rescue villagers who had fallen into the water.

Yun-Gui-Chuan was the nickname of an “amazing soldier” who emerged as a pivotal figure in the crucial breakthrough at Lazikou Pass [a narrow mountain pass that forms a gateway between Sichuan and Gansu, with historical significance due to its strategic importance in the final phase of the Long March]. As a young soldier from the Miao ethnic group, Yun possessed an innate talent for rock climbing nurtured since childhood. In order to find a way to break through the enemy’s fortifications at Lazikou, this young Miao soldier volunteered to scale the daunting cliffs. Yun successfully ascended to the summet, and was able to guide the troops to encircle and launch a surprise attack on the enemy’s rear. In tandem with the frontal assault, they executed their mission with precision and determination [unfortunately, Yun perished in battle with no one knowing his real name].

Guo Ting, who had just turned 18 years old, was ill when he marched into the grasslands with his troops. After marching for five or six days, the troops ran out of food, and were forced to slaughter their horses for food. In his final act of selflessness, Guo left his portion of horsemeat and half a jar of wild herbs for his comrades. He was laid to rest on that very grassland for eternity.

Piecing together history

Unlike books that offer a macro perspective on the Long March, Notes on Retracing the Long March begins from fifteen specific “details” such as Red Army graves, baron lanterns, straw sandals, silver coins, songs, and guides, and brings together these historical pieces to reconstruct the epic journey of the Red Army.

“The Everlasting Baron Lanterns” tells the stories of the locals who assisted the Red Army soldiers along their way. To express their gratitude, the troops bestowed many baron lanterns upon the local people, which were cherished as treasures. “Guide of the Red Army” focuses on the relationship between the Red Army and their guides, providing another key to understanding why the Long March succeeded. Traversing desolate landscapes, rugged hills, snow-capped mountains, and inaccessible grasslands, the Red Army relied heavily on local guides for navigation. The stories of those guides vividly illustrate the close relationship between the Red Army and the common people.

“Hometown That I Will Never Return” collects the stories of the Red Army soldiers who lost contact with their troops and the experiences of their descendants. During the Long March, some seriously injured soldiers and those who fell behind were scattered in numerous villages. These lost Red Army soldiers formed a unique group. The Long March took them far from their hometowns, where they settled down with the help of the locals along the way. Starting a new life in their “second” hometowns, they spent the rest of their lives repaying the kindness of the locals.

At Anshunchang, Sichuan, where the swift currents of the Dadu River flow, Wei raised the question of why the Red Army didn’t repeat the tragedy of Shi Dakai [Shi was one of the most competent generals in the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) that almost toppled the Qing Dynasty; he and his troops failed in crossing the river in 1863 and this failure caused his death]. The stories of the boatmen who had helped the Red Army cross the river provide some clues to the Red Army’s success, illustrating that solid support from the local people may have played a crucial role. They not only helped the soldiers traverse the river, but many of them also joined the Red Army.

Amidst the desolate grasslands, loneliness and fear often gripped those who lagged behind the advancing troops. Yet, despite the daunting challenges, they found the strength to persevere and emerge from the grasslands. Wei astutely observes that their salvation lay in the power of human connection. Within the team, a profound sense of camaraderie flourished, fostering an environment where every member felt the warmth of mutual assistance.

The panorama along the Long March route has undergone profound transformation over time. Walking along the Long March route today, one may observe people living in peace and enjoying the fruits of national development. This stark juxtaposition between past struggles and present prosperity underscores the monumental significance of the Long March, along which soldiers and commoners alike played untold yet significant roles in bringing peace and prosperity to China.

Dong Wenran is a guest research fellow from the Shandong Provincial Research Center of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.

Edited by REN GUANHONG