Desolate Lop Nor tombs exhibit distinctive Central Plains motifs

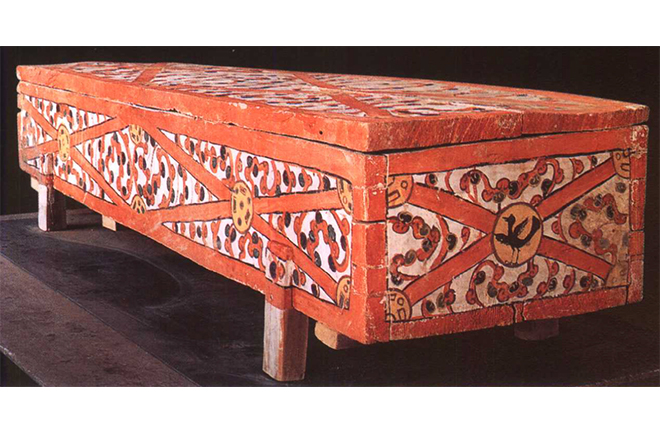

A painted coffin unearthed at the LE city ruins of Loulan in 1998 Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Since the excavation of Tomb M15 at Yingpan site in 1995, a series of painted wooden coffins dating to the Han (202 BCE–220 CE) and Jin (266–420) dynasties have been unearthed in Lop Nor, of the eastern Tarim Basin, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The “lian-bi” patterns [“bi” refers to a flat jade disc with a circular hole in the center] painted on the coffin boards are rich with Han cultural elements and empirically demonstrate the cultural connection between the ancient Central Plains and the Western Regions. Originating from decorations that involved connecting jade bi discs with silk ribbons, the lian-bi patterns are prominent features found on at least eight coffins dating back to the Han and Jin periods in the Lop Nor area.

Roots in the Han traditions

The tradition of painting coffins is deeply rooted in Han culture, and the origin of the lian-bi patterns can be traced back to the Central Plains. These patterns typically consist of bi discs and silk ribbons. The association of jade bi discs with silk ribbons can be traced back to the pre-Qin period, notably observed in the tombs of the state of Chu [which included most of the present-day provinces of Hubei and Hunan]. Within a Chu tomb located at Baoshan, Hubei, archaeologists documented the presence of jade bi discs suspended with bands inside coffins, a phenomenon interpreted by researchers as decorative linked bi in coffin, as recorded in the ancient classic Zhuangzi: “I regard heaven and earth as my coffin, with the sun and the moon as my linked bi discs...” The textile adorning the inner coffin in the Chu tomb in Zaoyang, Hubei, dating back to the mid-Warring States Period (476–221 BCE), provides a particularly vivid instance of the lian-bi pattern. This textile consists of 124 jade bi discs intricately interconnected with silk ribbons in a cross pattern.

The lian-bi coffin decoration observed in the pre-Qin Chu region was adopted by the Han tombs. In the Han tombs of Mancheng, Hebei, multiple jade bi discs were found placed on the chest and beneath the back of the tomb occupant’s jade burial suit [a ceremonial suit made of pieces of jade in which royal members in Han Dynasty were buried], with traces of strip-like textile fragments observed on both sides of the bi discs. Similarly, in the tomb of the Nanyue King in Guangzhou, one jade bi disc was placed at each of the four corners of the outer coffin lid, with traces of silk ribbons forming a cross pattern evident on the surface of the discs. The jade burial suit worn by the tomb occupant featured three layers of jade bi discs lined inside and out, also showing traces of silk ribbons.

In the instances cited above, both the jade bi discs and silk ribbons were physical objects and can therefore be described as lian-bi decorations. But pictorial depictions, namely lian-bi patterns, have also been observed on coffin boards and mural paintings in Han and Jin tombs. In terms of the tomb hierarchy, the privilege of being buried with physical lian-bi was reserved for the upper-class, as jade had become a luxury commodity during that period. As the popularity of lian-bi as a funerary custom grew, the derivative lian-bi patterns began to appear in tombs across all social classes. Nobles often opted to adorn lacquered coffins with painted lian-bi patterns, while the middle and lower classes depicted these patterns on stone reliefs.

By examining both the lian-bi decorations and lian-bi patterns from the Central Plains, it becomes possible to trace the cultural origins of the decorative patterns on the painted coffins in Lop Nor. The occupants of these painted coffins were also typically local upper-class figures, as evidenced by Tomb M15 in Yingpan. Here, the abundance of rich grave goods and the strategic placement of the tomb on a platform far removed from the main burial clusters underscore the prominent status of the tomb occupant.

Style and connotations

Jade bi discs and lian-bi patterns are not particularly rare in Lop Nor and its surrounding areas. Brocade embroidered with distinctive lian-bi patterns incorporated with beast motifs were found not only in Han and Jin tombs along the southern route of the Silk Road, but also in the more distant West Asian region. One such example was unearthed from the Kitot tower in the ancient city ruins of Palmyra, Syria (the tomb dates to 40 CE). This demonstrates that the lian-bi pattern was very popular during the Han and Jin periods, thus enabling its spread westward along the Silk Road to Xinjiang and even West Asia.

In 1906, during his exploration in Loulan, Marc Aurel Stein made a significant discovery: multiple wooden architectural components carved with lian-bi patterns at the LB site, which Stein described as “circular wheels connected by interwoven bands.” These carvings apparently also originated in the Central Plains.

The significance of the lian-bi patterns adorning the painted coffins in the Lop Nor region likely aligns with those from the Central Plains. As previously discussed, the essence of these patterns lies in the connection between “bi” and “silk.” Some scholars believe that this combination may represent a pictorial narrative rooted in prehistoric mythological beliefs, which considered jade bi and silkworms as divine objects. In pre-Qin eras, jade and silk were used as sacrificial offerings in ritual ceremonies. Thus, when lian-bi patterns appeared in brocades and architectural components, they reflected the contemporaries’ efforts to construct an environment that resembled divinity, with the intent to achieve transcendence and ascension to immortality. In tombs, these patterns were intended to guide the soul of the tomb occupant toward a transcendental state. Thus, the lian-bi patterns in different contexts reflect the Han people’s eternal aspiration towards ascension to immortality.

A testimony to cultural confluence

The Lop Nor region during the Han and Jin periods served as a hub where Eastern and Western cultures converged. Artifacts unearthed from sites and tombs of this period provide compelling evidence of the exchange and fusion of Central Plains culture, foreign cultures (such as Kushan, India, Persia, etc.), and local cultures.

During Zhang Qian’s tenure as an imperial envoy to the Western Regions in the late 2nd century BCE, the Central Plains dynasties initiated contact with and fostered development of the Western Regions. The beacon towers and military farmland sites in Lop Nor witnessed the central court’s efforts in developing and constructing the frontier regions. Local excavated items such as Han documents, Han-style bronze mirrors, lacquerware, and brocades reflect the profound influence of Central Plains culture on the local customs. Han-style painted wooden coffins, as funerary objects with lian-bi patterns, can be traced back to the practice of decorating coffins with linked jade bi discs in the Chu area during the Warring States Period, demonstrating the ancient aspiration for ascension to immortality. Moreover, accompanying burial items such as burial suits and silk fish [a decorative fish-shaped object made from silk] echo the funerary traditions of the Central Plains, displaying the profound impact of Central Plains culture on local customs.

The discovery of lian-bi patterns in the Lop Nor region provides evidence of the influence of Central Plains culture on the ancient Western Regions. The blending and restructuring of different cultures within the nation are a microcosm of the formation and development of Chinese civilization. The convergence and reconfiguration of diverse cultural elements within the nation’s borders reflect the intricate tapestry of influences that have shaped Chinese civilization over its 5000-year history.

Wei Wenbin (professor) and Huang Tingting (doctoral student) are from Lanzhou University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG