‘Modern’ traps in studies of traditional political thought

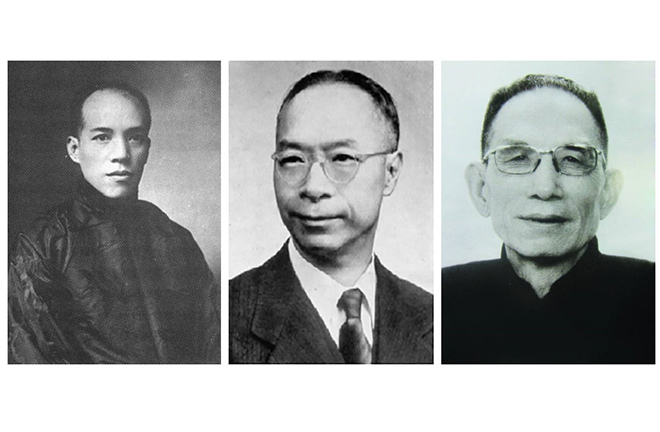

FILE PHOTOS: Liang Qichao (1873–1929), Xiao Gongquan (1897–1981), and Mou Zongsan (1909–1995) from left to right

Since the dawn of the 20th century, two Western theories have deeply influenced Chinese scholars as they study traditional Chinese political thought. The first is cultural evolution theory, also known as historical evolution theory. This theory posits that human history develops from lower to higher levels in a linear fashion, following a common evolutionary model from aristocracy, monarchy, to democracy and even nationalism. According to this theory, ancient Chinese political thought, especially Confucian political philosophy, failed to foster democracy, so it is described as “premodern.”

The second theory, institutional determinism, maintains that politics should focus on establishing normative institutions, instead of relying on the people. Confucianism values interpersonal relations, the rule of virtue, and merit-based appointment of officials. Considering the people more important than institutions, Confucianism reverses the relationship between the two and seriously diminishes the importance of political systems.

Under the guidance of these two major theories from Western humanities, most research on the history of ancient Chinese political theory centers around three arguments: people were placed at the center, or regarded as the root, of politics but had no rights to political participation; the rule of man, instead of the rule of law, was implemented; and autocracy was persistent while democracy didn’t exist in ancient China. These three perspectives are widely considered as the major problems of Chinese political thought, represented by Confucianism, over the past 2,000-odd years. This article will examine these views and problems likely to ensue, from studies of political theory conducted by renowned scholars Liang Qichao (Liang Chi-Chao), Xiao Gongquan (Kung-Chuan Hsiao), and Mou Zongsan.

Liang Qichao’s thought

The History of Chinese Political Thought: During the Early Tsin Period, a compilation based on the notes of lectures Liang delivered in 1922, was one of the earliest works to review the history of Chinese political thought through a modern lens. Many of the insights within this publication are still highly relevant. For example, the analysis of Confucian cosmopolitanism, which Liang labeled “real cosmopolitanism” and “super-nationalism,” is entirely consistent with prevailing discussions in recent years. His analysis of minben (people as the root, or people-centrism) pioneered research on this topic.

While Liang opposed the view that ancient Chinese people had no freedom or equality, he also called attention to late American President Abraham Lincoln’s emphasis on government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” According to Liang, ancient Chinese government was evidently “of the people” and “for the people,” but governance “by the people,” or the situation that all political affairs were handled by the people, was never admitted throughout the nation’s history. Therefore, Liang argued that the greatest shortcoming in Chinese political theory was that ancient China put people at the center of politics but didn’t grant them sufficient political participation.

From contemporary perspectives, Liang’s theory is biased. It’s fair to say that ancient Chinese people had no rights to engage in politics, but the claim that ancient China saw no discussion of minquan (people’s rights), and antagonized minben and minquan, was not necessarily factual.

According to the Confucian classic Shang Shu, or the Book of Documents, the will of heaven aligned with that of the people. As stated in the chapter “Great Oath,” “what heaven saw and heard originated from what the people saw and heard,” which seems to suggest popular sovereignty. In the same chapter, another statement—that heaven complied with the aspirations and demands of the people—implies that people had the power to overthrow a despotic government.

In prominent Confucian philosopher Mengzi’s commentary on ministers’ killing of the two tyrants Jie, the last king of the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070–c. 1600 BCE), and Zhou, the last ruler of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), Mengzi asserted that the ministers were exterminating “canzei” (robbers) and “yifu” (ruffians), rather than putting sovereigns to death.

Xunzi, another great Confucian thinker, compared the people and the ruler to water and the boat, respectively, saying “water can carry the boat but can also overturn it.” This view has been passed down from generation to generation till today.

Obviously, people had the right to oust tyrannical regimes in ancient China. Although Confucianism didn’t provide a system to enable people’s participation in politics, this does not mean that Confucianism overlooked minquan, people’s rights. It’s unfounded to understand Confucianism by pitting minben against minquan.

Xiao Gongquan’s theory

The masterpiece History of Chinese Political Thought authored by Xiao, which was first published in Chinese in 1945 and later reprinted many times, has been well received at home and abroad. The book discusses historical analysis at great lengths, while assuming an evolutionist conception of history.

For example, Xiao divided the history of Chinese political thought into the stages of creation, replication, transformation, and maturation. The first stage ranged from the time of Confucius (551–479 BCE) to the unification of China by the Qin Empire (221–207 BCE). The replication stage went from the Qin and Han (206 BCE–220 CE) dynasties to the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) eras. The transformation stage began in the early Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and continued till the late Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). Chinese political thought matured after the establishment of sanmin zhuyi, the three principles of the people raised by modern Chinese Nationalist leader Sun Yat-sen: minzu (nationalism), minquan, and minsheng (people’s livelihoods). Xiao’s division displays an evolutionary ladder of thought. He regarded sanmin zhuyi as the culmination of political thought in China.

Meanwhile, Xiao used the authoritarian, feudal, and modern eras to correspond to the above four stages and summarized the political ideas within. If the feudal era represents a judgment of facts, then the authoritarian period stands for value judgment. From the perspective of factual judgment, the period from the Qin and Han dynasties to the late Qing was characterized by junxian zhi, a bureaucratic prefectural system, paralleling the feudal era, so Xiao regarded the monarchy which occurred under this system as despotic.

However, compared to specific systems such as the monarchy, feudal system, and bureaucratic prefectural system, despotism doesn’t denote a certain polity or system, but a value evaluation of all systems.

Mou Zongsan’s view

One of Mou’s famous opinions was that China had an administrative democracy, but no political democracy. Administrative democracy generally means that Confucian governance philosophy pins political hope on sage kings and wise ministers. The absence of political democracy indicates that political power was not in the hands of the people; it was acquired by force.

Mou’s view also features a duality between democracy and autocracy, and between minben and minquan. In fact, autocracy doesn’t point to any particular regime, but refers only to a way of ruling. Using this logic, it is unjustifiable to say that democracy and autocracy are polar opposites. Chinese people have long been used to considering democracy a value criterion, so all non-democratic regimes can be deemed autocratic.

In addition, Liang, Xiao, and Mou each dichotomized the rule of man and the rule of law, yet in different ways. Liang incorporated Legalism into the rule of law and Mohism into the rule of man. Xiao pointed out that one of the biggest defects of traditional Chinese political thought was the failure to recognize the importance of respecting legislature and systems, seemingly the rule of law, and not relying excessively on human ethics and morality, the rule of man. According to Liji, or the Book of Rites, “if men of virtue were there, the government would flourish; and without them, the government decayed and ceased.” Mou said this is why the rule of law couldn’t be put in place in ancient China.

Nonetheless, as Liang discovered, the rule of rites advocated by Confucianism for thousands of years couldn’t be summarized simply as the rule of man. A growing number of scholars have noted that the developed ritual system in ancient China bears resemblance to the customary law in the West.

Institutional economics, which has been an influential school of economics in the West, objects to understanding systems through rigid law or written rules, contending that etiquettes and customs are also a part of institutions, and play an even bigger role than hard institutional provisions. In ancient China, there were numerous ritual and music systems, as well as decrees and regulations, so it is biased to conclude that ancient China was marked by the rule of man, without the rule of law, by placing the two in opposition.

In 2000, the winter issue of Dædalus, a journal sponsored by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, was titled “Multiple Modernities,” in which modernity was featured as a topical issue of global significance. Some scholars argue that modernity is not transcendental of a certain history or space, and it is not incomprehensible once we are divorced from a specific background.

For example, it was discovered that Europe, North America, Japan, and many colonies took different paths to modernity. Famed Neo-Confucian Tu Weiming proposed that modernity can be truly understood only by going beyond the binary mentality that separates tradition from modernity, West from non-West, and the global from the regional.

From the perspective of multiple modernities, the cultural evolution theory and institutional determinism that have influenced Chinese academia profoundly since the 20th century, as well as binary opposition of minben and minquan, rule of man and rule of law, democracy and autocracy, are worth reframing. Studies of traditional Chinese political thought will not be freed from the shackles of West-centrism until scholars find the way out of “modern” traps.

Fang Zhaohui is a professor from the Department of History at Tsinghua University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG