Chinese antiques give new insight into history of pentagram

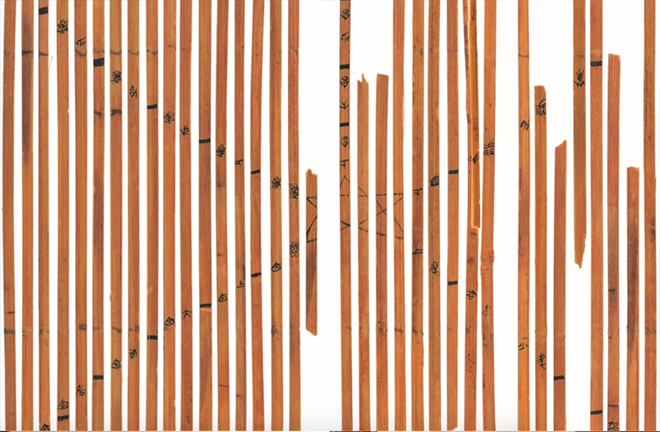

Carefully reassembled bamboo strips from the Warring States period, revealing an ancient musical notation in the form of a pentagram Photo: XINHUA

Pentagrams can be found over the world, bearing various connotations. While historically used as a symbol of the stars, such as in ancient Egypt, the pentagram more commonly serves as a geometric symbol unrelated to celestial bodies. The term “pentagram” originates from ancient Greek, originally meaning “five lines” intersecting to form a pattern. When did the earliest pentagram appear in China? A Liangzhu ceramic plate and the Warring States bamboo slips in the collection of Tsinghua University provide us with new clues.

Earliest instances of pentagrams worldwide

It was previously widely believed that the earliest pentagrams in the world originated in Mesopotamia, as evidenced by pentagrams engraved on clay tablets and vases dating to the Jemdet Nasr period (5,100–4,700 years ago). These pentagrams, drawn using a single continuous line, were not merely decorative motifs or symbols, but rather logograms representing the Latin word “UB,” meaning “corner.” Consequently, with the increasing simplification of cuneiform writing, the connection between the writing of this word and the pentagram largely diminished by the Akkadian period (2334–2154 BCE).

In ancient Egypt, Sopdet, the goddess of Sirius, was depicted with a pentagram above her head. In the Egyptian hieroglyphs, the pentagram also served as a character for the Latin words “sba” or “dua,” meaning “star,” “hour,” “morning,” while a pentagram inscribed within a circle symbolized the underworld.

Apparently, the pentagrams of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia differ in both shape and connotation. Pentagrams more closely resembling those from Mesopotamia has been discovered in the Liangzhu Culture (5,300–4,300 years ago) in China. Specifically, a ceramic plate unearthed from Tomb No. 204 at the Maqiao site in Shanghai, dating back 5,000 years, features an engraved pentagram surrounded by spiral lines on its inner bottom. This discovery leads to the conclusion that around 5,000 years ago, pentagrams appeared in Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, and China. Mathematically, the segments of the pentagram exhibit the golden ratio. Many creatures in nature, including five-petal flowers and starfish, also exhibit this ratio, and may have inspired the creation of pentagrams, offering an explanation for their widespread use by ancient civilizations across the world.

What message can be drawn from the Liangzhu pentagram? Chinese archaeologist Wang Ren-xiang believes it more likely to be a symbol of a specific celestial body, with the surrounding spiral lines representing its movement. Some scholars posit that the pentagram was possibly inspired by the trajectory of Venus, as the planet traces a perfect pentacle across the ecliptic every eight years. While this idea gained popularity following its inclusion in the novel The Da Vinci Code, there is no solid evidence establishing a direct relationship between Venus and the pentagrams found in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt.

If the Liangzhu pentagram indeed symbolizes a celestial body, it is possible that sun worship may also be involved. Images of eight-pointed stars have been discovered in archaeological cultures such as the Gaomiao, Lingjiatan, Dawenkou, and Liangzhu. On many of China’s Neolithic Age relics, patterns featuring “horns” (actually representing light) often symbolized the sun. Notably, a “bronze wheel” was unearthed at the Sanxingdui site, resembling a car steering wheel with a spherical shape in the center emitting five rays around it, and a circle on the outside. This shape bears a striking resemblance to the circled pentagrams from ancient Egypt that represented the underworld. Considering the numerous indications of sun worship exhibited in Sanxingdui culture, it is plausible that the wheel-shaped object is indeed associated with the sun.

Possible connection with ancient music

In December 2023, Tsinghua University released the findings of a new study on bamboo slips, which included an unknown text on pre-Qin music—the “Diagram of Five Tones.” Through the efforts of the research team, this text, which has been lost for more than 2,000 years, has been meticulously reconstructed. The reconstructed music theory diagram features a pentagram at its center with five traditional Chinese musical notes written in the five corners. Positioned at the top of the pentagram is the note gong, followed clockwise by the remaining four notes known as shang, jue, zhi, yu.

Researchers also observed that when the note gong is used as the starting point, the pentagram can be drawn in one stroke following the sequence “gong→zhi→shang→yu→jue.” This order adheres to the fundamental principle known as the “three-point profit and loss method.”

Ancient Chinese scholars long ago discovered a correlation between the length of the bamboo lü tuning pipe [ancient Chinese musical instruments constructed for tuning purposes] and the pitch it produced. With the same diameter, the shorter the pipe, the higher the pitch. This allowed them to convert the invisible and intangible pitches into numerical values that could be calculated based on the intermediary of length. According to the ancient classic Guanzi, given a first pipe length, i.e. 81, representing the note gong, the second pipe would be increased by one-third of 81, producing a length of 108, corresponding to the note zhi. The value of the note zhi minus one-third of 108 is 72, which is the value of the note shang. When shang is increased by one-third of 72, 96 is obtained, representing the note yu. The value of the note yu, minus one-third of 96, is 64, which produces the note jue.

The “three-point profit and loss method” is recorded both in the Guanzi and Shiji. However, the former follows an order “from addition to subtraction,” while the latter “from subtraction to addition.” The larger the value obtained, the longer the tuning pipe is and the lower the pitch. According to the numerical values calculated in Guanzi, the order from low to high pitches is “zhi-yu-gong-shang-jue.” The order calculated based on the Shiji is “gong-shang-jue-zhi-yu,” which is more commonly used.

It is said that Pythagoras invented the famous “Pythagorean tuning,” which bears striking resemblance to China’s “three-point profit and loss method” leading to frequent confusion between the two. The “Pythagorean tuning” and the “three-point profit and loss method” were, however, cultivated in distinct cultural contexts within ancient Chinese and Greek civilizations. While they share similarities, there are also notable differences. For example, the “Pythagorean tuning” is a system of musical tuning in which the frequency ratios of all intervals are based on the ratio 3:2, while the “three-point profit and loss method” embodies two processes: “minus one-third of the previous note” and “increased by one-third of the previous note.”

Pythagoras held the belief that numbers underlie the fundamental laws of the universe, and his exploration of music theory was deeply rooted in mathematics. Similarly, the unearthed documents of the Warring States period also emphasized the laws of the universe contained within mathematics. The “three-point profit and loss method” documented in Guanzi is likewise based on mathematics. Intriguingly, the pentagram not only appears on the Chinese bamboo slips but is also believed to be a symbol associated with the Greek mathematician Pythagoras and his disciples.

About 5,000 years ago, in the budding civilizations of the Tigris, Euphrates, Nile, Yellow River, and Yangtze River, the ancients independently discovered the balanced beauty behind the geometric figure of the pentagram, almost as if by prior agreement. From 600 to 300 BCE, during the “Axial Age” (coined by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers), philosophers from China and ancient Greece explored the universal laws governing numbers and music, endowing the pentagon with special connotations. From this we can feel the similar rhythm of the development of human civilization.

Chen Minzhen is an associate research fellow from the Institute of Chinese Culture at Beijing Language and Culture University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG