Relational thinking constructs path for Chinese psychology

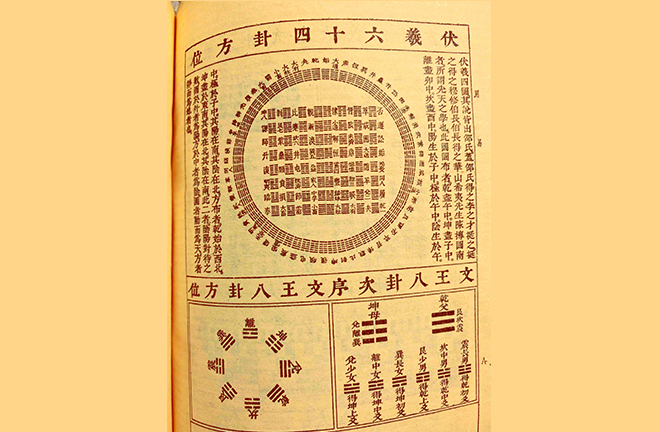

爻 (yao, lines in bagua, the Eight Diagrams) in Zhou Yi, part of I Ching, symbolizes the relation itself, and can be regarded as a symbol for all beings in the world. Photo: Chen Mirong/CSST

History of Chinese Psychology, a book compiled under the chief editorship of pioneering Chinese psychologist Gao Juefu, is considered a groundbreaking work for the history of Chinese psychology as a field of study. During the compilation process, members of the editorial board discussed a wide array of issues, eventually reaching a consensus that ancient China had rich psychological thoughts, but no systematic research was conducted as in Western psychology.

This consensus is still shared by domestic psychological theorists and experts on the history of psychology today. It is generally believed that before Western psychology was introduced, China only had psychological thoughts, but there was no “psychology” in the sense of modern science. This article will examine the possibility of constructing Chinese psychology or a Chinese model of psychology based on the relational thinking pattern unique to traditional Chinese culture.

Attempts to indigenize psychology

The development of psychology in China stemmed from the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program, which aimed at financing Chinese students to be educated in the United States with excess funding from the Boxer Indemnity at the start of the 20th century.

Following the Boxer Uprising in 1900, the Qing court was forced to sign the Boxer Protocol and paid a massive sum for reparations to foreign nations. In 1908, the US Congress passed a bill, authorizing President Roosevelt to return part of the Boxer Indemnity, which exceeded the United States’ real financial loss, to China. It was suggested that this fund be used to help China run schools or to support Chinese students to study in the United States.

Most early Chinese psychologists received an education in the United States. Western psychology was introduced to China exactly at that time, as Chinese psychology began to develop. In 1917, Chen Daqi and other scholars founded the first psychology lab in China at Peking University, marking the birth of Chinese psychology. However, Chen didn’t study in America; he went to Japan.

After completing studies in the United States and returning to China, these scholars started to build the Peking University psychology lab and teach the discipline, introducing, testing, and applying Western psychology.

In fact, domestic psychologists are still engaged in work of this kind. They haven’t established Chinese psychology or constructed a Chinese model of psychology yet. A Chinese psychology model would be a complete system of psychological concepts, theories, methods, and applications, built by Chinese researchers, demonstrating the distinctive features of Chinese culture and running parallel to Western psychology.

In the 1970s and 1980s, several psychologists from Chinese Taiwan and the mainland underscored the need to “study Chinese people as Chinese people,” and committed themselves to adapting psychology to the Chinese context. Their endeavors evolved into a campaign to indigenize psychology in China. Regrettably, they failed to build a whole or unified theoretical and practical system of psychology.

The problem with this indigenization attempt lies in that although such topics as renqing (rules for handling interpersonal relationships), mianzi (face), filial piety, zhongshu (loyalty and forgiveness), and zhongyong (the doctrine of the mean), which are typical in Chinese cultural situations, were studied, imprints of individual rationalism in Western culture were obvious in researchers’ approaches and theories, particularly in terms of underlying worldview, methodology, and epistemology. Therefore, the indigenization or Sinicization was not thorough.

Forty years of experience and lessons in adapting psychology to the Chinese context indicate that to construct a Chinese model of psychology, it is essential to dive deep into the foundational level of methodology and form an intact psychology system with Chinese characteristics. The system should include methodologies, basic concepts, theories and approaches, and various practical applications of the discipline.

Just as individual rationalism is characteristic of Western psychology, a relational thinking pattern should be the most salient feature of Chinese psychology. Western psychology has a coherent conceptual and theoretical system, encompassing cognition, emotion, willpower, and behavior; process psychology and personality psychology; perception, memory, and thinking. Chinese psychology also needs to build a conceptual system and develop Chinese concepts like mianzi, renqing, and zhongxiao (loyalty and filial piety) into theories, exploring ways to explain psychological phenomena and solve people’s mental illnesses through the lens of Chinese culture, which then should be extensively applied to social life and practice.

When dealing with interpersonal social relationships, understanding the relationships among humanity, nature, and the universe, and interpreting individual life trajectory, psychologists should absorb notions and theories about human psychology in Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism of Chinese culture, constructing a Chinese model of psychology through creative transformation and innovative development.

Distinct relational thinking

To build a Chinese model of psychology, two tasks are involved. First, scholars should continue to draw upon and absorb concepts, theories, and research outcomes from modern Western psychology. For Chinese psychology to “go global” and be understood, accepted, and recognized by Western psychologists, concepts and language that can be understood by both sides must be used. It is inadvisable to close our mind, which will make it impossible to dialogue on international communication platforms on an equal footing. Second, efforts are needed to uncover intellectual resources from traditional culture, to examine the essential features and spiritual connotations of Chinese cultural traditions, as well as various manifestations in daily lives and work, including the ways Chinese people live, think, and behave today.

To fulfill these two tasks, we need to simultaneously implement psychological research and studies of traditional culture, two totally different fields. Research in psychology is empirical, requiring methods similar to those employed within the natural sciences, while studies of traditional culture are theoretical, historical, and critical. The two fields follow different research paradigms but are both vital to constructing Chinese psychology.

The relational thinking pattern might be an “Archimedean fulcrum” for the construction of Chinese psychology. Different from subject-object dichotomies common to Western culture featuring individual rationalism, relational thinking emphasizes that two seemingly oppositional sides actually precondition one another’s existence and are always in a relational process of mutual transformation and fulfillment. The relational mentality is in stark contrast with the three laws of Western formal logic: the law of identity, law of contradiction, and law of excluded middle.

Western culture tends to exhibit a unidirectional logic. For instance, A is A and is not non-A; there is no middle expression. On the contrary, the Chinese relational mindset is complex and highly flexible. Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism in Chinese culture all have traces of relational thinking.

Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism

In Confucianism, the doctrine of the mean is a relational concept. As renowned Song-Dynasty neo-Confucian philosopher Lu Jiuyuan (1139–1193), who founded the school of thought “Xinxue,” or the “Learning of the Mind,” said: “my mind is the universe, and the universe is my mind.”

After Lu, Wang Yangming (1472–1529) further built a complete system for the Learning of the Mind and put forward such famous ideas as “the mind itself is truth,” “all people have the innate capacity to discern moral truths naturally through moral introspection,” and “unity of knowledge and action.” Among other concepts, such bifurcate pairs as mind and substance, emotion and reason, knowledge and action, moral introspection and practical research are linked as indivisible wholes or relational existences, and these concepts are in a constant process of mutual transformation.

Western philosophy is inclined to divide objects into two opposing sides, while traditional Chinese culture prefers to integrate two into one, viewing a single object or different facets of a single concept within a whole, or a dynamic system comprising the opposite sides. This is what relational thinking is about.

Taoism is even more representative of this mentality. I Ching, or the Book of Changes, focuses on the principles of conversions between yin and yang. The character爻 (yao, lines in bagua, the Eight Diagrams) in the masterpiece symbolizes the relation itself, and can be regarded as a symbol for all beings in the world. It suggests that all things, objects, and matters are interconnected and can never be divided. Connections, or relations, change with time and space. If we can grasp the dynamics of time and space, we can master the “Dao,” the way the world operates, and foresee the future.

Gao Juefu summarized ancient Chinese psychological thoughts into 10 categories: heaven and humanity, humans and non-humans, body and spirit, disposition and habit, knowledge and action, mind and substance, emotion and desire, ideal and intention, intelligence and ability, and wisdom and tactic. Each category derives from the Taoist meta-category of yin and yang. The two elements of each pair seem separate but are integrated. They coexist and depend on each other, evolve into each other in symbiosis, and are in a dynamic, harmonious equilibrium. All these categories reflect the relational mentality.

Buddhism teaches that everything happens for a reason and is neutral. According to the Avatamsaka Sutra, on Indra’s net, which is woven with numerous precious pearls, all the pearls reflect each other in an intricate, endless fashion. It implies that all humans and things are intertwined and interact both as cause and effect, an essential feature of relational thinking.

Unique to traditional Chinese culture, the relational mindset contrasts with individual rationalism in Western psychology and mirrors the fundamental difference between Chinese and Western culture. Building a Chinese psychology model based on relational thinking doesn’t mean to reject Western psychology. In fact, the Eastern and Western cultural stances can complement each other.

Western psychology segments human psychology into units to meet requirements for empirical measurement and experiments, while relational thinking in traditional Chinese culture posits that psychological elements exist within inseparable relations, systems, dynamic changes, and processes. The latter is significant to the psychological healing of self-defined or independent individuals who are involved in excessive competition due to individual rationalism. It can also provide clear guidance for the development and reform of contemporary education and organizations, and has methodological value for research in psychology and other fields of humanities and social sciences.

Yang Liping is a professor from the School of Psychology at Nanjing Normal University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG