Nature holds different value in Chinese and Western literature

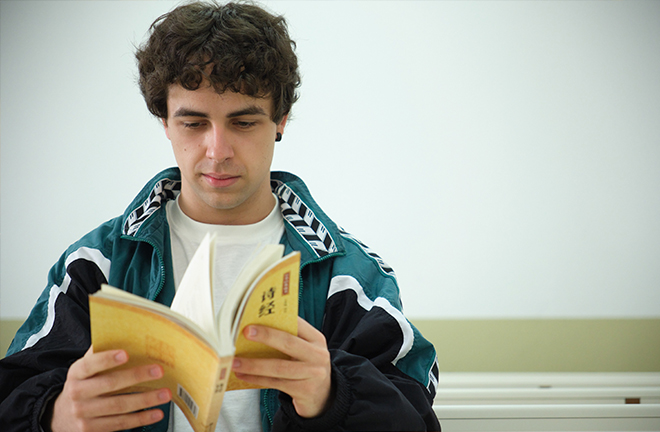

A student reads Shijing, or the Book of Songs, which reflects the traditional Chinese literary view of nature, at the Autonomous University of Madrid in Spain. Photo: XINHUA

Since antiquity, nature has been a significant theme in Chinese literature, and the outlook on nature reflected within demonstrates Chinese people’s unique demeanor and contains salient intrinsic qualities of Chinese civilization. Poetic works about landscapes, objects, idyllic life, and border themes all portray Chinese people’s sincere and plain view of nature, documenting their expressions of self and their explorations of the world in distinctive ways.

In a recent interview with CSST, Wolfgang Kubin, whose Chinese name is Gu Bin (顾彬), a distinguished authority on Chinese cultural history and a lifetime professor at the University of Bonn in Germany, offered his insights into the traditional Chinese literary view of nature.

Kubin emphasized the inseparable relationship between the development of human civilization and the natural world, asserting that this connection has been integral to the development of Chinese civilization. The traditional view of nature showcased in a wealth of Chinese literary works since the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) has been closely related to social production, historical realities, and national development, changing with dynastic evolution and mirroring the development trajectory of Chinese civilization. As observers of nature, Chinese literati instilled their ideas and emotions into nature, endowing it with subjectivity and personality. They used the landscape as a medium for contemplation, integrating their observations, perceptions, and reflections.

Different evolutionary paths

Discussing the difference between Chinese and Western literature and painting in portraying nature, Kubin noted that the two traditions have different origins. Nature was first regarded as perceptible landscape by Westerners in 17th-century Dutch paintings. However, not until the 18th century, when Western capitalism and industrial society developed rapidly, did nature appear in European lyrics as a formal subject of literature, as it was leveraged to escape from the bustling world and voice objection to social restrictions.

Kubin acknowledged the earlier presence of nature in Western artworks, but in a relatively minor supporting role. Nature was neither an external reality that could be made sense of alone, nor a cultural vehicle to reflect human subjective consciousness.

On the contrary, Kubin continued, nature had emerged as an appreciable being independent of humanity as early as in literary works of the Zhou Dynasty, and the notion was developed further in the Han era (206 BCE–220 CE). In the Six Dynasties (222–589), a consciousness of nature among Chinese men of letters had been universal in literature, paintings, and garden arts. The traditional Chinese view of nature climaxed in the Tang Dynasty (618–907), which provided models for literati of subsequent dynasties, ranging from the Song (960–1279) to the Qing (1644–1911), to depict nature.

Through decades of research on Chinese literature, Kubin has drawn a preliminary conclusion that classical Chinese literary works had already revealed a unique view of nature more than 1,000 years earlier than in the West.

Richer connotations

According to Kubin, the term “ziran,” or “nature,” has richer connotations in traditional Chinese society than in the West. It encompasses not merely the phenomena of the physical world collectively, such as plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth. Nature also represents an outside world beyond itself—a power in the universe that can bear on all beings, Kubin said.

Quoting founder of Taoism Laozi as saying, “man patterns himself on the operation of the earth; the earth patterns itself on the operation of heaven; heaven patterns itself on the operation of Dao; Dao patterns itself on what is natural,” Kubin explained that Laozi’s claim is a typical illustration of early traditional Chinese thoughts on nature. In China, the landscape is regarded as a lively, real, and independent subject, prompting conscious efforts to explore and grasp its beauty.

In Western literature, Kubin further pointed out, portrayals of nature didn’t show a figurative nature until the 18th century. By contrast, in China, literary works of the Zhou Dynasty had already featured elegant and rhetorical depictions. In early Western society, literati did not necessarily describe nature based on what they had seen, but mostly in light of “legendary nature.”

This means the nature penned by early Western men of letters was depicted as divorced from farming and social production. By contrast, in traditional Chinese society, the perception of nature evolved in close ties with agricultural labor, social production, and dynastic developments, Kubin said.

More profundity

It’s safe to say that the outlook on nature, as a manifestation of self-consciousness, is more profound in classical Chinese literature than in Western works, Kubin told CSST. Nature not only constitutes the material foundation for the existence of traditional Chinese literati, but also serves as a spiritual pillar for their literary creations, representing a medium via which realities and their emotions penetrate each other.

He noted that in certain Western countries, many scholars blindly applied the research approaches of Western literary history to Chinese literature studies due to inadequate research methodologies, thus resulting in misunderstandings.

For example, some scholars likened Tang-Dynasty poetry to Western Romantic poetry, a juxtaposition Kubin pointed out as ridiculous in 1976. Meanwhile, in his book Chinese Literati’s Ideas on Nature, he also corrected certain biases held by Western scholars. In Kubin’s opinion, the traditional literati’s perception of nature in Chinese literature never developed independently of society, and can be examined and understood through three major stages: the period from the Zhou to Han Dynasty, the Six Dynasties, and the Tang Dynasty.

Chinese poetry is the most important “communicator” of the traditional Chinese literati’s outlook on nature, Kubin said, adding that this outlook can also be found in Chinese fu (rhyme-prose), ci-poetry, epistolary pieces, travel notes, and landscape prose.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG