Tracing Chinese experiences from Latin American cinema

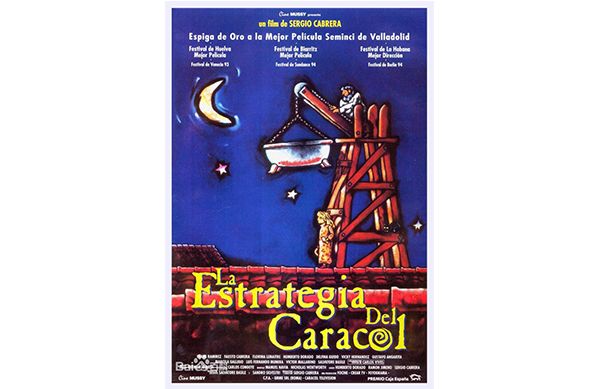

FILE PHOTO: A poster of the film “La estrategia del caracol” (1993) directed by Sergio Cabrera

In a recent forum, Zhao Weifang, director and research fellow, Qin Xiqing and Sun Meng, research fellows, all from the Institute of Film and Television at the Chinese National Academy of Arts, and Wei Ran, associate research fellow from the Institute of Foreign Literature at CASS, explored the subtle connection between the development of modern China and Latin American cinema.

Possible inspiration sources

Zhao Weifang: “Latin American cinema vs. Chinese experience” is a new topic, encompassing the literature, drama and film realms in Latin American countries, especially Colombia, as well as the interaction with China. It leads us to ponder the historical interactions of the left-wing literary and artistic experiments between China and Latin America. Such reflection may bring inspiration to constructing a new “global South” cultural community and a new internationalist trend. Latin American literature, drama, and film are important components of world art. The Chinese elements in Latin American art deserve focus and in-depth study.

‘Look Back’

Wei Ran: The new book Volver la vista atrás [Look Back] by Juan Gabriel Vasquez, the most internationally influential contemporary novelist from Colombia, tells the true stories of the Colombian film director Sergio Cabrera and his father, Fausto Cabrera (1924–2016). The book depicts their life and work experiences in China, providing important materials for tracing the 20th-century left-wing literary and artistic linkage around the world, and offering an alternative path to exploring the Chinese experience within Latin American cinema.

Although Volver la vista atrás is based on real people, it is classified as a novel rather than a biography. This is because the book presents the Chinese experience having greatly affected Colombia as well as readers from the contemporary Spanish-speaking world, and such experiences cannot be simply conveyed by a family biography or national development history. Novels can better capture the ambiguous experiences of the world to explore the landscape of cross-border interactions of left-wing literature and art around the world, thus it has long been obscured by the post-Cold War era.

Attracted by traditional Chinese opera, Vsevolod Emilyevich Meyerhold’s theatrical concepts, Japanese proletarian theater, and the revolutionary progression in China, Fausto Cabrera worked in China for six years during the early 1960s. Not only did he participate in the establishment of the Spanish major for Chinese education at that time, he also contributed to Chinese film production and helped translate Chinese works into foreign languages. After returning to Colombia, Fausto took Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art” as a blueprint, and worked obsessively on his art career over the radical decade (1965–1975) of “el nuevo cine latinoamericano” [the New Latin American Cinema].

Sergio Cabrera, another protagonist in Volver la vista atrás, spent his youth in Beijing, where he was deeply involved in socialist activities, and even worked in a factory. Sergio entered the film industry by participating in the creation of “How Yukong Moved the Mountains” [a series of 12 documentary films directed by Marceline Loridan-Ivens and Joris Ivens] in the early 1970s. His movie “La estrategia del caracol” [“The Strategy of the Snail,” 1993] explores how new collectivism can be found in the neoliberal era. Through the story of a group of tenants living in an old house confronted with having to move out due to a renovation project undertaken by the city of Bogotá, the movie presents the people’s wisdom in fighting in the face of defeat. It proposes that in the face of an unshakable repressive system, the symbolic resistance achieved through cinema represents a way for people at the bottom to reclaim their dignity. As a representative Colombian film, “La estrategia del caracol” explores in an allegorical way the possibility of new collective actions when the global left-wing cause was at its low ebb in the 20th century.

Through the clues provided by Volver la vista atrás, we can try to outline the byways of global history when China and Latin America affected and interacted with each other over the topic of left-wing literary and artistic experiments. Following the global epidemic and the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the drawbacks of the old hegemonic system have been fully exposed, and a call for a new “Global South” cultural community has emerged. Examining Latin American films and literary writings that encompass the Chinese experience may boost the formation of a new internationalist narrative.

Reconstruction of global perspective

Qin Xiqing: The discussion of Latin American filmmakers’ experiences in China in the 1960s brings us back to that passionate era. We can interpret the rise of socialism and left-wing ideas by locating it at the context of a longer historical period—the two world wars. The global landscape during the Cold War, Mao Zedong’s Three Worlds Theory, etc., directly affected the cultural exchanges and interactions between countries. The connection between China and the Cabreras is a vivid example of these trends.

After the reform and opening up, the Chinese film industry in the 1980s was partly influenced by Western film theories, particularly those of the French. In the 1990s, industrial reform and commercial development became key words for Chinese movies, and Hollywood received more attention. Along the way, Latin American films were gradually forgotten. Today, more and more young Chinese scholars have begun to pay attention to Latin American films again. They are attempting to regain a more balanced and comprehensive global perspective, and step out of the current world film landscape centered on European and Hollywood films. The vision of a new “Global South” cultural community proposed by Mr. Wei Ran also provides a reference for considering the future development of Chinese culture.

Influence and inspiration

Sun Meng: The first part I’d like to share is the influence of Latin American literature on Chinese films. The Chines film “Bloody Morning” (1992) directed by Li Shaohong is adapted from Gabriel García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Although the movie has been localized, viewers can still detect the traits of Latin American literature from the barbarism, ignorance, backwardness, and murder in the desperately poor village. Many Chinese writers in the 1980s and 1990s, such as Mo Yan and Yu Hua, drew inspiration from Juan Rulfo and Márquez, and this influence was indirectly transplanted into Chinese films.

Next, I’d like to talk about what China can learn from Latin American film. First, we must acknowledge its avant-garde nature. Latin American films absorb and draw on local arts such as Latin American literature, poetry, and painting, developing powerful creativity and vitality. In addition, Latin American filmmakers attach great importance to their own folklore, myths, and history, seeking roots and inspiration from their culture. These efforts endow their films with distinctive cultural features. Latin American movies highlight the motive of pursuing freedom, which is also worthy of attention. The fourth point worth learning is the allegorical nature of Latin American movies. When telling stories related to personal experiences, many Latin American films tend to include narrations on the experiences of the collective. Moreover, the Chinese filmmakers can draw inspiration from the artistic expression of magical realism in Latin American movies.

In general, cultures need to flow towards each other. Artists should feel and absorb the changes in the world around them, significant or miniscule, and obtain a global perspective. Absorbing Latin American experience is to find something original to our own. What is most important is to focus on our inner renewal and gain more artistic vitality.

Edited by REN GUANHONG