Online literature criticism carries dual connotation

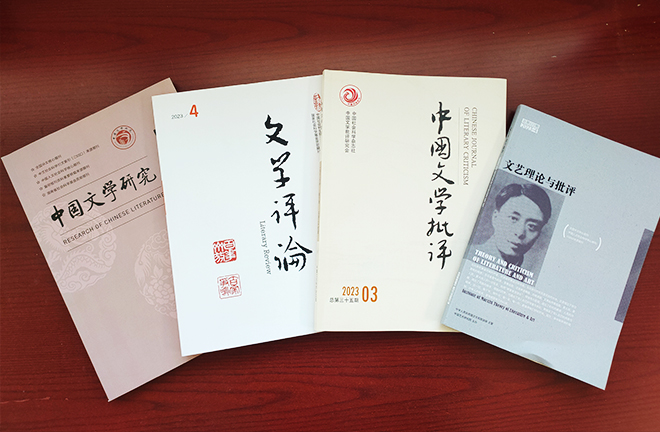

Traditional literary critics have not yet begun to analyze online literature, which now has a massive presence. Photo: Yang Xue/CSST

The term, “online literature criticism” has two meanings: First, it refers to literary criticism published on the internet, which can include evaluations of either online or traditional printed literature; Second, it describes the critique of online literature itself. Critique of online literature may appear on the internet or in printed publications. The internet is so groundbreaking and unique that it quickly blurred the well-defined distinctions between critical discourse and literary works.

In history

Literary criticism published on the internet doesn’t necessarily represent a revolutionary innovation, in terms of either literary concepts or technical analysis models. Most literary criticism has not undergone a seismic shift due to the new publication method. However, literary scholars encounter unique terms in internet-based literary criticism, such as “strong start and feeble finish,” “golden figures,” or “working on a follow-up to a previous piece of creative work.” These terms are often transferred from casual colloquial language and are humorous, sharp, and populist in nature, while they may lack substantial theoretical depth. Thus far, the internet has not brought forth new textual interpretation theories for literary criticism.

In the history of ancient Chinese literary criticism, there were countless cases when literature was spontaneously critiqued. These critiques were quick, incisive, candid, and straightforward, reflecting unreserved thoughts. Ancient literary criticism of popular works is not significantly different from the current online environment. The scholarly norms which require substantial literary evidence and comparison came later to the field of literary criticism. Therefore, the populist, lively, and outspoken style of literary criticism we see today is not novel, it has long thrived in print media.

If we were to describe the changes brought by literary criticism published online, the speed of dissemination is a remarkable feature — unparalleled in print media. The speed of digital circulation can change traditional relationships between critics, texts, and modes of interpretation, and may even transform critique into an integral component of “web content.” In the internet economy era, the speed of publication and content dissemination is closely related to online traffic. More clicks indicate more website turnover and a larger audience. The instantaneous transmission and reception of electronic signals determines real-time communication on the internet. When literary criticism enters this system, some characteristics previously preserved by print media almost imperceptibly vanish.

One connotation for critique

First, the interactive atmosphere created by the internet gradually takes the place of thoughtful and deliberate analysis. Personal opinions become competitive, and bombastic writing takes precedence, but over time, progressively layered logic quietly takes the lead. Second, the internet’s noisy revelry inhibits rebuttal mechanisms. Revelry draws loud and synchronous responses rather than in-depth intellectual dialogue. Jokes, sarcasm, mockery, or fake astonishment, cannot overshadow a rigorous theoretical analysis. Even though different inclinations and viewpoints exist, online critics often do not take the time to calmly articulate a contemplative essay. At this point, online literary criticism revives the long-debated question – Who holds the truth: the many or the few, the masses or the experts?

Experts in the field of literary criticism usually have a strong background in literary knowledge. Professional training in literary analysis is a prerequisite for engaging in literary criticism. This demands a deep understanding of the evolution of literary history, familiarity with literary classics, and proficiency in various literary theoretical propositions. However, professional training can sometimes cultivate a culture of elitism.

Some critics may not openly advocate for the academic elite, but they promote the idea that the public benefits from elevated aesthetic taste and a higher culture. Acknowledging this, critics subtly question whether the seemingly popular works that the public has favored truly represent the interests of the masses. Even when a critic’s rational analysis exposes the simple tricks woven into intricate storylines, popular works still hold immense market appeal. In many cases, critics’ views do not resonate with the public.

Literary criticism published on the internet often sparks a counterattack from fans, who rebel against the implied elitism and authority of academia and established professionals. Critics who operate in the online realm place a high degree of trust in their intuitive sensibilities and assume that people universally share the same feelings and thoughts. In many cases, counterattacks may expand into a disdain for traditional literary knowledge. It’s evident that critics think that they are aligned with the general public.

However, online communities usually come together in response to outlying critiques of their favorite authors. Communities have organized on online platforms for only about 20 years, since the birth of the internet. Nevertheless, online literature, characterized by fragmented reading, highly stylized writing, and happy endings, with an impossibly vast volume, has already created a strong community of readers. Readers are confident in the power of their community, and often threaten to “unsubscribe and stop reading” to demand that authors revise their storylines to cater to community preferences. This technique often results in the revisions they requested.

Another connotation

Online literature criticism also refers to the critique of online literature. Before discussing the second meaning for this term, it’s important to establish some simple commonalities: traditional literary criticism in print media is often found within academic circles, it emphasizes theoretical propositions and literary classics, and it is typically governed by a group of knowledgeable experts. In contrast, online literature criticism is often straightforward, candid, and unfiltered, as critics and reading communities engage in critical debates together. These differences are so great that some argue that online literature cannot be included in an academic critical review.

Indeed, traditional literary criticism in print media doesn’t pay much attention to online literature. Online literature, particularly web novels, have grown to represent a massive cultural zeitgeist, but it seems that critics who rigorously follow academic standards have largely overlooked this form of literature. While arrogance might account for this, the simpler reason seems to be that critics often don’t know where to begin. Online literature, especially web novels, are resistant to textual analysis.

The simplicity and shallow charm of online literature, which primarily aims to provide escapism and uncomplicated joy, are to a large extent rooted in modern “daydreams.” These fantasies have no history. However, the mechanism for satisfying this desired escape is subject to history. A significant portion of all literary content is drawn from author’s imaginations, and literary criticism often evaluates whether fiction aligns with historical logic.

In fact, historical analysis is a substantial component of literary criticism. Authors and critics share an implicit premise: Literature must release the constraints imposed by historical logic. Literary fiction is not an arbitrary fabrication, and doubts surrounding any fictional work’s “historical authenticity” can seriously disrupt the aesthetics of literature.

However, when literary fiction abandons historical logic and solely follows desires, literary content becomes so simple that it leaves little room for literary criticism. While a daydream might not have any history, if the social context fulfilling this fantasy world is simultaneously removed, literary narratives become as simple as a curve from the rise of a dream to its fulfillment. The individual becomes a dream subject without a tether to reality or history.

Online literature has also introduced several literary strategies to escape the gravity of history, and the repeated use of these literary strategies has given rise to literary genres such as martial arts, time-travel, and fantasy, among others. These online literature genres provide rough molds which the average story is compressed through. Plots and characters are mostly identical within these genres, making detailed literary criticism seem like a waste of time. However, with professional training centered around literary classics, is it possible to uncover other issues within the massive trove of online literature?

‘Digital humanities’

As the study of “digital humanities” gains popularity, it is now possible to analyze online literature’s massive word count. Digital humanities builds on large-scale statistical analysis, computation, databases, and other research methods associated with computers. When compared to literary critiques published online, digital humanities opens up a fresh space within the literary criticism spectrum, introducing numerous research topics and new critical pathways. Digital humanities provides a solid data foundation for categorizing long-term or large-scale literary characteristics. While critics may marvel at the explosive growth of online literature, digital humanities easily confirms many speculations and hypotheses. When applying digital humanities to the context of online literature, several aspects should be considered.

First, the conclusions generated by the study of digital humanities may depart from traditional categories found in literary criticism, such as separating distinct works and authors. Digital analysis no longer compares online works to literary classics, nor does it delve into the specifics of how individual authors select themes, design plots, or choose their wording. The new topics introduced by the digital humanities do not aim to improve traditional literary understandings, but rather, expand the scope of literary meaning.

Second, digital humanities must find new questions rather than confirm unchanging conclusions. This may involve gathering data to substantiate certain hypotheses, or increased data might lead to the recognition of new problems, the problem-oriented awareness which is inherent within the digital humanities is indispensable.

Third, the large-scale statistics uncovered by the digital humanities offers a macroscopic perspective. The digital models resulting from an accumulation of vast data remove unique individual characteristics and identify common patterns. In this context, whether it’s the ebb and flow of plot design or an overall overview of genres, it is much easier to find patterns in online literature than in literary classics, making it easier for “digital humanities” to interpret these patterns.

The tendency to follow “routines” or “patterns” is precisely what separates classical literature from online literature. A fixation on recurrent themes or expressions implies a lack of historical originality, a key criterion for evaluating classic works. Online writers tend to align their work with readers’ tastes, which confines their seemingly diverse imaginations to a few simple routines. Within the increasingly stable cycle of literary production and consumption, a massive “information cocoon” appears.

When “digital humanities” simplifies the vast amount of text into clear charts and graphs, authors have a better understanding of their works and their blind spots. In the end, such an extensive literary landscape mainly consists of an aggregation of a few common “daydreams.” At this point, authors and readers must reconsider a fundamental question: Is the pursuit of mechanical one-dimensional pleasure the goal of literature?

Nan Fan is from the Fujian Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by YANG XUE