Chinese people’s endogenous dynamics rooted in culture

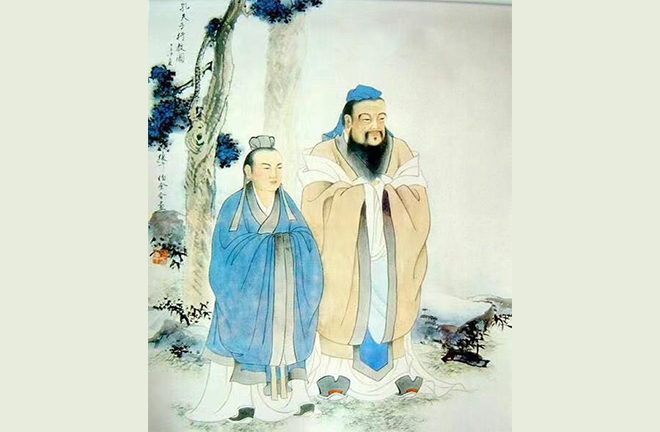

FILE PHOTO: Confucius (right) and his disciple Yan Hui, who held different attitudes toward life

The aspiration for a better life is concerned with individual autonomy and agency. Using the lens of psychology, specifically the branch of personality psychology, the endogenous dynamics underlying Chinese people’s aspirations for a better life can be better understood through personality dynamics. Both “endogenous dynamics” in Chinese discourse and “personality dynamics” in Western psychology are essentially about motivations behind human behavior.

It is generally believed that endogenous dynamics are a mental force driving and affecting individual behavior and decision-making. These involve basic desires, emotions, needs, moral codes, and adaptability to the real environment. Why do some people continuously strive for higher goals, while others firmly believe in fate and choose to “lie flat?” To answer these questions, it is necessary to examine the mechanism of individual endogenous dynamics, which is subject to historical, cultural, and contextual influences.

Limits of personality dynamics

Studies of personality dynamics can be traced back to Freud, whose study of pan-sexualism considered libido, the sexual drive, to be the intrinsic motive underlying all human behaviors. Freud’s personality theory consists of personality structure, personality dynamics, and personality development. Personality psychologists of later generations mostly followed the architecture of Freud’s personality theory when observing the dynamics of personality.

For example, American psychologist and educator Gordon W. Allport defined personality as a “dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that determine his unique adjustments to this environment.” Robert R. Sears believed that personality dynamics can reveal reasons for contradictory and conflicting individual behaviors. Kurt Lewin argued that studying human behavior’s dynamic features is the key to understanding behavior, and that behavior refers to changes of the state in the temporal dimension.

After reviewing the disciplinary framework of Western personality psychology, Chinese scholar Guo Yongyu interpreted personality dynamics as reasons for, and driving forces behind, personality performance. This includes personal motives, conations, emotions, attributions, and individual adaptability to the environment.

Recent studies have begun to focus more on the temporal dimension of personality dynamics, maintaining that personality dynamics represent personality’s short-term changes and a related latent mechanism in a certain culture or context.

These studies indicate that research of personality dynamics cannot be divorced from culture or context—a vital background variable. Scholars should not blindly apply the personality dynamics theory constructed in the Western culture and context to another culture.

Endogenous dynamics’ cultural roots

As people’s inner drive in the Chinese cultural context, endogenous dynamics can never be thoroughly understood from the perspective of Western personality dynamics. It is necessary to unpack the way endogenous dynamics is viewed in Chinese philosophy, history, culture, and society, and understand its implications in the Chinese context.

When Western philosophers were pondering the constituents of the universe, Confucian scholars had shifted their focus from “heaven” to humanity and called for close attention to human motivations for such purposes as cultivating virtues, achieving independence, and developing self-consciousness. They reflected on how people can regulate, operate, and settle down in their lives through their own efforts.

While the West was interpreting the wider world using knowledge, Confucianism was looking inward, to uncover how humans can bring peace and stability to their own country, and expand that harmony worldwide through their personal endeavors. This fostered the people-centered spirit of “seeking causes from within oneself.” In this spirit, two important concepts became deeply rooted in the inner world of Chinese people and formed their endogenous dynamics: “cultivating morality to live up to the mandate of heaven” and “self-improvements.”

From “revering heaven” among people of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), to “cultivating morality” in the subsequent Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), the concept of “tiandi,” lord of heaven, gradually disappeared, as Chinese ancestors shifted their focus from divine intervention to self-cultivation. The idea of cultivating morality to live up to the mandate of heaven meant that humans began to count on themselves, demonstrating personal agency in their endogenous dynamics. As long as people cultivate morality, they can master their destiny with virtue. From then on, humans took over the autonomy from the hands of gods and became ever more independent and self-reliant.

In the Confucian classic The Analects, “Master said: Is virtue a thing remote? I wish to be virtuous, and lo! Virtue is at hand.” This statement suggests that Confucius believed humans are capable of self-improvement, to reach the state of “ren,” being benevolent. Confucius maintained that ordinary people could become successful and even outstanding figures through their own endeavors.

Apart from the requirement for an enterprising spirit, Confucianism also stressed the importance of leading a simple yet virtuous life. For example, Confucius traveled to several states in the hope that monarchs could adopt his suggestions, dreaming of bringing top-down enlightenment to the land, while his disciple Yan Hui was contented in poverty and maintained a happy state of mind by sticking to his moral principles. This shows that the endogenous dynamics in Confucianism are not monotonous. They oscillate between faith and facts and don’t set a contextual standard for determining when to step forward or back.

However, Confucianism’s emphasis on ideals and responsibility might constrain people’s endogenous dynamics and trap them in self-inflicted trouble and pain. So how can we reduce this moral tension and derive pleasure from hard work? In the face of unchangeable realistic conditions, how can individuals transcend predicaments in life to gain spiritual enjoyment and the feeling of freedom?

Different from Confucianism’s advocacy for self-motivation, Taoism upholds “wuwei,” or non-action, emphasizing following the natural course and maintaining inner peace despite difficulties.

Laozi valued meditative reflections on the miseries of life, while Zhuangzi was interested in breaking away from the tough life. As Zhuangzi pointed out, people should deal with hopeless scenarios in human society with an awareness of “mingxian,” or the limits of fate, striving to keep a peaceful mind and retain the vigor of life by applying new perspectives to life’s bitterness.

Laozi’s thought mirrors a naturalistic attitude toward life, while Zhuangzi called for an easy and carefree enterprise. This enterprise represents a process of self-transformation. It requires individuals to take things as they are first, then recognize their own abilities and limitations, to free their minds from meaningless struggle, and finally, seek their respective meaning while acknowledging and emancipating themselves spiritually. This process doesn’t involve the immortality of souls or the existence of gods, but the intelligent intuitive inherent in the real self, as humans and all beings in nature form an indivisible unity.

Taoism’s theory of endogenous dynamics is grounded in the pursuit of synchrony with nature, based on the totality of the cosmos, which differs vastly from the Confucian pursuit of realistic worldly values.

Implications for today

Old Chinese sayings, such as “those who keep up their efforts often achieve their goal; and those who keep on walking often reach their destination,” “one reaps no more than what he has sown,” and “fortunes or misfortunes are all created by man himself,” tell us that whether one can succeed or not largely depends on whether they have worked hard or not.

In real life, however, we find individual efforts will not necessarily bring expected results. Under such circumstances, we seem unable to resist the impact of decisive factors beyond our control. As many Chinese believe, human life is predestined. Destiny is inescapable and predetermined regardless of human interventions. In this context, what attitude shall we hold?

In his work History of Chinese Philosophy, renowned philosopher Lao Sze-Kwang summarized the Confucian enterprise on the premise of fate with the concept “yi ming fenli,” which means yi (righteousness or justice) and ming (destiny or fate) should be viewed separately. Fate is external and beyond human control. Within the scope of fate, humans are actually unfree. However, righteousness is internal, and subject to personal definition, which grants freedom. For example, being born unintelligent is one thing, but choosing to work hard is quite another. No one can choose how they were born, but they can decide whether to strive for a better self or not. Although people might not succeed after unremitting efforts, because no one can control many external factors of life, we should still do what’s right and perform their duties as best as they can.

Under the influence of yi ming fenli, Chinese people generally embrace the attitude of “doing one’s best” and “leaving the rest to heaven.” Doing one’s best means people should go all out in what should be done, and if they still fail, after making greatest efforts, they must surrender to heaven or fate. Therefore, doing one’s best stands for individual autonomous efforts.

On the other side, leaving the rest to heaven means accepting the natural course of life. Confucianism proposes first maximizing effort to ensure that one holds no regret over missed opportunities, before entering the stage of leaving the rest to heaven.

All in all, previous studies of endogenous dynamics mostly adopt an etic approach, or impose existing Western theories upon Chinese people, so that it becomes difficult to understand the real foci of Chinese people’s endogenous dynamics. There is also a lack of in-depth analysis of the inner drive’s dynamic course. In recent years, some Western scholars have argued that endogenous dynamics include a set of concepts with a pluralistic structure, but their conceptions of the topic are overly simplistic. Scholars need to conduct indigenous, deep research of Chinese people’s endogenous dynamics from the perspective of cultural subjectivity.

Wu Na is a doctoral candidate from the Faculty of Psychology at Southwest University, and Huang Xiting is a senior professor of psychology at the university.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG