Sun Li’s poetry mirrors China of the 20th century

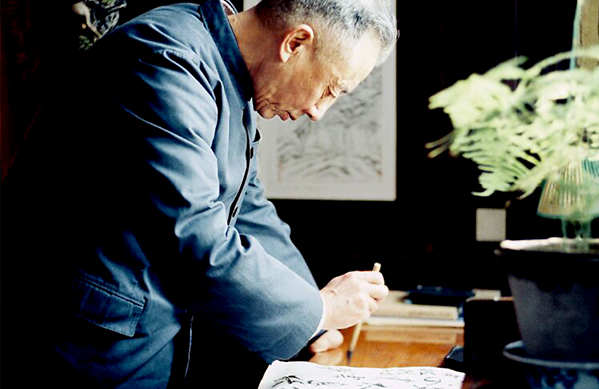

The Chinese writer Sun Li practicing calligraphy at home Photo: Courtesy of ZHANG XUAN

Though well known as a novelist and essayist, Sun Li (1913–2002) had dreamed of being a poet. Throughout his illustrious career, he penned poems corresponding to different stages of modern and contemporary Chinese literature, demonstrating his distinct poetic vision and insight into his own life.

Starting point

Sun’s career as a poet began in April 1934, when he published his debut poem titled “I Have Decided” under the pen name “Yun Fu” in a supplement to the Ta Kung Pao on April 26. The protagonist in the poem departs from his hometown determinedly, heading towards a city. However, frustration and psychological distance from urban life bring out the worst in the city, as presented to the protagonist. From a perspective of a social observer, Sun exposed the exploitative nature of the city under its glamorous cover–“some people are transfusing blood into the others.” This poem signified the inherent traits of Sun’s poetry. He inherited an important tradition of classical Chinese poetry—poetry to express an author’s aspirations—and was fully concerned with reality.

Sun’s poetic creations can be divided into two stages. From 1938 to 1943, he mainly wrote long-form, narrative poems such as “The Story of Lihua Bay” “The Ballad of Baiyangdian” and “Spring Plowing Ballad.” He summarized his writing experiences during that time as “During China’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, I was strongly interested in writing poetry. Marching on the road, verses crossed my mind frequently. It was not surprising. When taking a break, I would take out my tiny notebook and put it on my lap. The verses were short, so it was easy to write them down quickly. I wrote in the wind and rain, at dawn and dusk. Those years provided a rich source of inspiration for a person to become a poet.” Sun infused revolutionary cultural elements into his long narrative poems. He created a series of heroic characters, laying the foundation for his famous collection “Lake Baiyangdian” [the area around which Sun’s stories associated with the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression are set].

Echoes of the new era

Entering a new era [after the founding of the PRC], Sun’s poetry experienced a resurgence, reaching a new zenith that endured until the mid-1980s. He captured the evolving social landscape in a simple and straightforward style.

Sun emphasized the importance of critically reviewing history. In the poem “Monkey Street Performance—A Childhood Memory,” he wrote about how deeply moved he was by the “fearful eyes” of a monkey in a street performance. Through his own personal experiences, he skillfully depicted ordinary moments of daily life and transformed them into tangible representations of introspective contemplation.

Sun’s poetry abandons pure romanticism and moves towards a more introspective and contemplative approach. This philosophical style of writing represents the artistic style of a group of writers in the 1980s. At the beginning of the poem “Seagull,” Sun described his first impression of seagulls—the pure and sacred birds. He then mentioned his Seagull watch, which was broken, leading to his lamentation about seagulls, constantly questioning how they face the sea and storms. Clearly, the malfunctioning watch and the seagulls in the storm correspond to the dark moments in his life. He wished for the ability to endure the storms of life by being as tough as a rock.

In Sun’s later literary creations, he often looked back at his life, trying to summarize it in his writing. He likened himself to an “old tree” that remains “young inside” even though it had “weathered too much storm and rain.” This “tree” yearns to encounter “little birds” and “flowers,” yet harbors a fear that birds will eventually fly away, and the flowers will wither. Consequently, Sun sighed in his poem: The old tree begins to sigh/ It is so fragile/ There will be no more fantasies,/ hopes,/ and self-indulgent/ With great concentration,/ the tree will finish what it has started,/ walking through its ordinary life,/ as it always has done (From “The Old Tree”).

Lu Zhen is a professor from the School of Literature at Nankai University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG