Chinese civilization featuring a long, continuous history

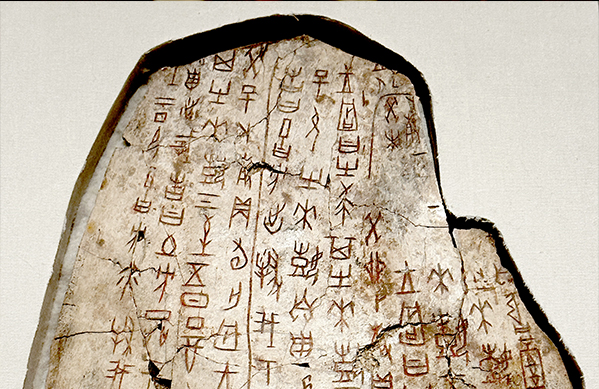

A piece of inscribed Shang Dynasty oracle bone unearthed at Henan, preserved at the National Museum of China Photo: Ren Guanhong/CSST

The origin of Chinese civilization can be traced back to the late Neolithic Age over 5,000 years ago. In recorded history, this era is known as the early period of the “Five Emperors” [a group of mythological rulers existing in the period that preceded the Xia Dynasty (c. 21st–16th centuries BCE)]. This period corresponds to the later stage of the Yangshao culture, a famous archaeological culture in the middle reaches of the Yellow River. Social division of labor and wealth stratification emerged in the late period of the Yangshao culture, by which time many large settlements and even cities had already appeared. Around the same time, the Dawenkou culture in the lower reaches of the Yellow River, and the Daxi and Liangzhu cultures in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, also had similar-scale sites and early cities.

Advent of civilization

The creation of writing is significant. Early forms of writing, which directly influenced later Chinese characters, were discovered in the Dawenkou and Liangzhu cultures, which were adjacent to each other. Later, the Longshan culture in the Central Plain, evolving from the Yangshao culture, cultivated a series of early cities and early written materials. These factors, along with the discovery of small bronze utensils across various regions, are often regarded as crucial material symbols of the advent of civilization.

In terms of archaeological discoveries, several large ancient city sites or remnants from this era have been unearthed. These include the Liangzhu ancient city in present-day Zhejiang, the Shimao ancient city in Shaanxi, and the Taosi ancient city in Shanxi. Various exquisite artifacts were unearthed from these sites, including jade items, stone tools, large pottery utensils, musical instruments, masks that were probably used for witchcraft or entertainment, and some early written symbols. All of these indicate that people of that time had already entered the early stage of civilization.

The era of “Five Emperors” saw the emergence of a sociopolitical organization known as qiu-bang or zu-bang [chiefdom, a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship], which could be classified as a “quasi-state.” Ancient Chinese texts describe this period as a magnificent scene of “ten thousand chiefdoms coexisting within the society,” an exaggeration of the vast number of chiefdoms in China at that time. The Yellow Emperor, the Flame Emperor, and Chi You [a descendant of the Flame Emperor] were probably leaders of chiefdoms or alliances of local chiefdoms at that time. War, a product of civilized society, also appeared, including the Battle of Banquan and the Battle of Zhuolu between tribes recorded in Shiji and many other ancient Chinese texts.

Later, on the basis of chiefdom alliances, states appeared—the Xia, Shang (c. 16th–11th centuries BCE), and Zhou (c. 1046–256 BCE) dynasties. According to the Book of Rites, the society prior to the Xia was “Datong” [lit. Great Unity], characterized by primitive communism. Succeeding the Xia was “Xiaokang,” referring to civilized society. The Xiaokang society embraced the notion that “the kingdom is a family inheritance,” and “Great men imagine it is the rule that their states should descend in their own families. Their object is to make the walls of their cities and suburbs strong and their ditches and moats secure. The rules of propriety and of what is right are regarded as the threads by which they seek to maintain in its correctness the relation between ruler and minister; in its generous regard that between father and son; in its harmony that between elder brother and younger; and in a community of sentiment that between husband and wife; and in accordance with them they frame buildings and measures; lay out the fields and hamlets (for the dwellings of the husbandmen); adjudge the superiority to men of valour and knowledge; and regulate their achievements with a view to their own advantage. Thus it is that (selfish) schemes and enterprises are constantly taking their rise, and recourse is had to arms” (trans. James Legge). The Book of Rites regards private ownership, families, ritual systems, wars, social institutions, hereditary systems, and other features of the Xiaokang society as symbols of civilized society, which is reasonable. However, attributing all the civilizational elements of Xiaokang society to the Xia, Shang, and Zhou is still open to discussion. Archaeological findings suggest that a considerable part of these civilizational elements had already existed during the “Five Emperors” era. In other words, “Five Emperors” marked the initial steps of China’s journey into civilization.

Consistency of Chinese civilization

The Chinese nation began in the era of the “Five Emperors.” At that time, various tribes in the west [within China] regarded the Yellow Emperor as their leader, and gradually integrated with some tribes in the east through wars. The descendants of the Yellow Emperor, also known as the Zhou tribe, continued to conquer eastward. The Zhou people called themselves Xia, and addressed zhu-hou, the rulers of vassal states, as “zhu-xia.” After those vassal states merged into one, the new community was still called zhu-xia.

In ancient times, the characters “hua” and “xia” had the same pronunciation and were interchangeable. Therefore, “zhu-xia” was also referred to as “zhu-hua” or simply “hua-xia.” This is why the Chinese nation calls itself hua-xia.

The notion that China became a unified multi-ethnic centralist country only during the Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (206 BCE–220 CE) dynasties, implying that a unified political institution did not exist prior to that, is a subject of debate. The political entity of a unified state had already taken shape during the Western Zhou Dynasty. In fact, the territorial extent of the Western Zhou surpassed those of the preceding Xia and Shang. Through the feudal system, the Western Zhou achieved effective rule over the people within its territory, including the man, yi, rong, and di [the ancient hua-xia people used those titles to distinguish themselves from the so-called barbarians living around them]. The political institutions and systems of the Western Zhou were also inherited by later dynasties. The national fragmentation during the Spring and Autumn (770–476 BCE) and Warring States (475–221 BCE) periods was caused by the decline of the central power in its later years. The Qin and Han unified the nation again during their reigns. For a long time afterwards, the rule of each dynasty did not exceed that of the Zhou Dynasty. Therefore, the political entity of a unified state had been established in China for over 4,000 years.

Shen Changyun is a professor from the School of History and Culture at Hebei Normal University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG