Find storytelling in Chinese artworks

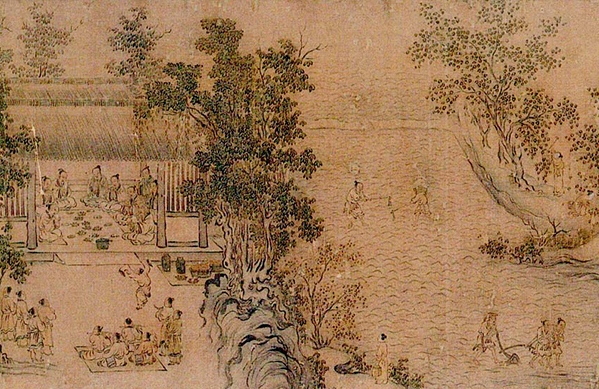

FILE PHOTO: A detail of “Odes of Bin” by the Southern Song artist Ma Hezhi

Walter Benjamin used “the Storyteller” to summarize the social role of traditional European artists: through the transformation and beautification of daily experiences, these folk storytellers have shaped the imagination of the general public with their flexible and rich expressive skills.

Carved in stone

Li Zhongrong: The paintings of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) were mainly represented by stone carvings [stones carved with images and used as construction materials], pictorial bricks [bricks stamped with images], and murals found in Han tombs. The subjects of Han paintings can be divided into two categories: scenes from everyday life and scenes from mythology. Both categories are narrative, and the temporal and spatial “dimensions” of the narrative content are presented through the configuration of the images. There are two main types of image configuration: independent configuration and separated configuration.

An image of independent configuration reflects the linear view of time. This type often depicts processions, such as traveling by carriage and horses, or deities marching with mythological beasts.

Images of separated configuration were created by dividing a large stone surface into several small horizontal sections with horizontal lines, with each section containing an image. In this way various characters or events from different times and spaces were assembled together.

Han paintings were created using scattered perspective and focal perspective. The Han images usually employed equal angle perspective, meaning multiple moving viewpoints are used in each picture. This perspective is characterized by its portrayal of human and other subjects from a side view, utilizing two techniques. The first technique is akin to forced perspective photography, while the second involves dividing the body below the head (typically done with animals), into two halves and presenting both sides simultaneously within the image.

Focal perspective is commonly used in Western drawing but is rare in traditional Chinese painting. To achieve equidistant perspective, the viewpoint must be constantly moved and changed, resulting in infinite viewpoints for observing and capturing subjects, finally presenting a three-dimensional image. This is more commonly seen in the ancient stone carvings found in Shandong Province.

In early times, both China and the West used scattered perspective to graphically depict three-dimensional objects and spatial relationships on two-dimensional planes. The application of focal perspective in the fine arts of the late Eastern Han period indicates the emergence of three-dimensional thinking. However, this technique was not successfully transmitted to future generations.

'Seventh Month'

Wu Han: “Seventh Month” from the “Odes of Bin” chapter is the longest poem in the Guofeng category [referring to poems collected from different states, bearing obvious local flavors] in the classic Shijing, or Book of Songs. Bin was a place in the present-day Xunyi and Bin counties, Shaanxi. During the era of Duke Liu, who was believed to be one of the founders of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), Zhou was yet an agricultural tribe. The poem “Seventh Month” depicts how the Zhou tribe lived and worked throughout the year, covering all aspects of their daily life.

“In the seventh month, the Fire Star [Antares] passes the meridian; /In the ninth month, clothes are given out. /In the days of [our] first month, the wind blows cold; /In the days of [our] second, the air is cold; /Without the clothes and garments of hair, How could we get to the end of the year? /In the days of [our] third month, they take their ploughs in hand; /In the days of [our] fourth, they take their way to the fields. /Along with my wife and children, I carry food to them in those south-lying acres. The surveyor of the fields comes, and is glad” (trans. James Legge). This first chapter is an overview of the entire poem.

Chapters 2 to 8 are about how men were responsible for agricultural labor and women for “domestic” chores. “In the ninth month, it is cold, with frost; /In the tenth month, they sweep clean their stack-sites. /The two bottles of spirits are enjoyed, And they say, ‘Let us kill our lambs and sheep, And go to the hall of our prince, /There raise the cup of rhinoceros horn, And wish him long life, that he may live forever’” (trans. James Legge). This latter half of the last chapter means that after a year of hard work, people can gather together and enjoy themselves with feasting and other celebrations.

The celebration in the tenth month in the last chapter echoes the Fire Star passing the meridian in the seventh month in the first chapter. The ancient people were able to achieve a bountiful harvest at the end of the year due to their timely observation of subtle changes in celestial phenomena, which allowed them to prepare their clothing and food in advance.

A comparison between this poem and the painting “Odes of Bin” by Ma Hezhi (1130–1170), a Southern Song artist, shows that the “Odes of Bin” does not depict all the contents of the poem, nor does it follow the original order of the text. However, the painting grasps the most crucial logical structure of the poem—from the Fire Star in the seventh month to the celebration in the tenth month, thus creating a style that has profoundly influenced later generations.

‘Literature in Line’

Zhang Xiaodi: As a printed medium that incorporates text with image, lianhuanhua [a type of palm-size picture books of sequential drawings popular in China in the mid and late 20th century] connected novels and movies with other art forms. In the early stages of China’s reform and opening up, and with the prosperity of the cultural market, lianhuanhua entered its golden era, when a large number of high-quality pieces were produced.

However, in mainstream art history, consumer-oriented images like lianhuanhua are excluded from the mainstream narrative, and their artistic value is often overlooked. Lianhuanhua have gained significant cultural and economic value in recent years, due in part to the rise of art auctions. As a result, these works have become highly sought-after cultural relics that attract a great deal of attention.

In the early stages of reform and opening up, following the aesthetic pursuit of Chinese realism, a unique visual art form was formed—movie-style lianhuanhua. In 1977, the journal Picture Stories published a set of drawings mocking opportunists, co-created by Xia Baoyuan and Lin Xudong. This set was inspired by a character from Lu Xun’s novella, “The True Story of Ah Q.” Although it was created in the ink painting style, the artists employed the chiaroscuro technique that is often used in oil painting, deliberately highlighting the contrast between light and dark, thus creating a movie-like atmosphere. This style can be regarded as a movie-style lianhuanhua.

A large number of such works emerged during this period attracting favorable comment and promoting the adaptation of contemporary literature. Many well-known painters active in the field of revolutionary-themed posters, educated youth painters, literary and art workers, and art lovers all engaged to the creation of this new type of lianhuanhua.

In the early days of reform and opening up, illustrated magazines could be regarded as a kind of “exhibition hall.” In the context where modern art had not been publicly displayed and discussed, they provided it with an influential display platform. The editors played the role of curator by participating in the negotiation of the art creation through editing and inviting artists for contribution.

Illustrated magazines also gave birth to a corner for art criticism. Large amount of readers’ letters and expert criticisms actually exceeded the boundaries of the text itself, expanding to literary, fine arts, film, and other domains, thus achieving the communication and integration between public discourse and official discourse.

After 1985, there was a sudden rupture in literary and artistic fields such as fine arts and film [as an avant-garde art movement flourished between 1985 and 1989], and the cultural industry became increasingly professionalized and systematic. Lianhuanhua was hit hard. After the 1985 Avant-Garde Movement, illustrated magazines gradually faded from the public eye, and lianhuanhua turned into the folk art form that we see today.

Edited by REN GUANHONG