Local chronicles add aesthetic appeal to rural fiction

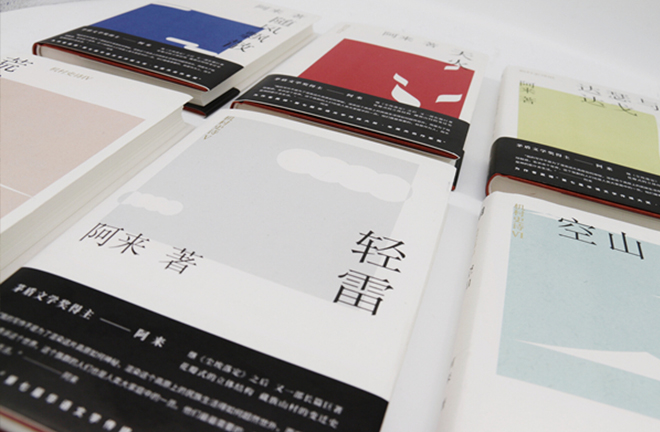

FILE PHOTO: A Lai’s six-volume series Epic of Ji Village

Local chronicles, or chorography, are historical records of a locality, covering history, geography, social customs, natural resources, the economy, culture, and so forth. Together with genealogical chronicles and national history, they constitute the three major pillars for historical and cultural studies of China. Incorporating local chronicles into fiction can illustrate a national destiny, while paving the way for plot to unfold, so these materials are vital to literary creation.

As a special genre of rural fiction in the 21st century, chorographic writing refers to adding content or elements from local chronicles into novels set in the countryside. Good examples include Desert Rites authored by Xue Mo, A Lai’s Epic of Ji Village series, Benhua by Tie Ning, Huo Xiangjie’s Local Knowledge, Chi Zijian’s Snow Crow, etc.

Through development in the 1980s and 1990s, chorographic writing in rural fiction has been a luminary approach in the landscape of 21st-century Chinese literature.

Evolution of rural fiction

For more than a century, imagination about the countryside in rural fiction evolved from enlightenment, pastoralism, revolution, root-seeking, on to local chronicles. The evolutionary process is like an artistic mirror reflecting social development in China.

Chorographic writing is not only an innovative development of Chinese traditions, but also a creative transformation of modern literary creation approaches. Many writers attempted to construct a sense of history from contemporary social realities amid rural fiction’s transition at the turn of the century.

Since the dawn of the 21st century, with the deepening of globalization, writers’ anxieties about cultural identity have turned into an empirical cultural consciousness. Their local awareness was gradually fostered and has become increasingly intense. Many writers chose to seek breakthroughs within the rural world, as chorographic writing has gained prominence in the literary community. In their artistic pursuit, they coincidentally began writing about Chinese experiences in a highly localized form.

Such “landmarks” in rural fiction, such as the “Lyuliang Mountain” in Li Rui’s serial novels, “Qinling Mountain” in Jia Pingwa’s works, and Fu Xiuying’s “Fang Village,” draw the map of Chinese rural fiction, evidencing the richness of Chinese culture in an artistic manner.

Obviously, using local chronicles to narrate country life is an effective way to dialogue with world literature. It provides an answer to the longstanding question facing contemporary Chinese literature: how can novels demonstrate both modern and global elements when depicting realities of local life in China?

This literary model has become a remarkable literary phenomenon in the 21st century, also because writers have urgently sought to rescue cultural heritage through literary creation. At present, as the national strategy of rural revitalization is being implemented in growing depth, rural society is developing into a modern one. Meanwhile, traditional rural forms are undeniably on the wane, raising a pressing need to include local chronicles in rural fiction. Many writers consciously shoulder this cultural mission by keeping records of realities through literature and recounting history through fiction, making chorographic writing in rural fiction a highlight of the literary landscape.

Chorographic writing models

Chorographic writing in rural fiction has taken on varied art forms. Novels of this type mainly draw upon local chronicles in form and content.

In terms of form, rural novels first follow the general style of local chronicles. In literary creation, writers pattern their works after the narrative model of local records. For example, Sun Huifen’s Recording Shangtang showcases shifts toward modernity in contemporary villages in an encyclopedic fashion. Borrowing the content classification model from local chronicles, the novel introduces changes in everyday life and local customs in Shangtang Village amid modernization from the nine aspects of geography, politics, transportation, communication, education, trade, culture, marriage, and history. From an outsider’s perspective, Sun’s work sheds light on the conflict between modern and rural civilization.

When talking about the distinctive feature of the book, Sun said that the distinctiveness doesn’t lie in how the novel breaks conventions, or the narrative model of embedding characters into the village, the subject of the novel, nor in how it loans native terms about geography, politics, transportation, and communication and breaks away from a story-based structure. It is distinctive because of the serenity and peace permeating every word and line, and for the calmness and objectivity, like voiceovers in narrative films, which arises from the infusion of reality into history.

The artistic effects of serenity and peace, calmness and objectivity are largely owed to replicating the style of local chronicles.

Since the 1990s, when many female authors tended to write on the basis of their personal life experiences, an individualized creation wave has caught on. Writers like Lin Bai and Chen Ran have produced a host of vanguard feministic novels. In contrast, Sun’s novels are divorced from the creation model which outlines personal survival experiences, reaching out to a broader real world that transcends the self.

Some rural novels also draw upon specialized records from local chronicles, such as records of personages, natural resources, customs, or sceneries and objects. Typical examples of novels imitating records of personages include Weihuzha of A Person written by Wei Wei, and Liang Hong’s The Holy Family. Li Rui’s Things in Peaceful Times is a good example of copying records of sceneries and objects.

Another, and more universal, type of rural fiction makes references to the content of local chronicles. Novels of this kind fall further into three subcategories based on the content they borrow. The first subcategory consists of works which entirely integrate facts from local chronicles in order to reproduce the original picture of history. Take Jia Pingwa’s Shanben, as an example. Effectuating a spatial shift from Shangluo to Qinling in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province, the work artistically displays historical changes and local constants, as well as the tension between rich implications and detailed texts, through the encyclopedic style of chorography.

Novels of the second subcategory use local chronicles as background knowledge and flexibly refer to the records, in an attempt to envision the possibilities of contemporary China, as exemplified by Wang Yuewen’s Home Mountain. The third subcategory invents stories with local chronicles as the narrative basis, seeking to innovate fiction’s form and allegorize rural novels.

Merits of chorographic writing

Chorographic writing has brought profound changes to contemporary fictional theory and artistic views. It enlivens and advances theories and methodologies for researching traditional Chinese regional culture.

First, local chronicles are historical studies of localities. Whether character, object, or narrative, chorographic writing centers around the relationship between humans and localities, building characters’ personality in the regional space and emphasizing the environment’s influence on human thought and emotion, value choice, and regional traits. In the meantime, narrating incidents in complex local geographical environments and cultural networks carries forward traditional Chinese geography.

As Wang Yuewen recalled, when writing Home Mountain, he collected and consulted a wealth of historical documents and local records, studied the household registration, land, and field systems as well as methods for tax and levy collection, and went many times into the field in the countryside for field investigation. The aim was to return to life itself, and present histories of social life, rural folklore, and changes over time. Through Shawan Village, he intended to showcase the vicissitudes of the times and the continuity of the Chinese nation. Local experiences in the novel indicate China’s stories, and the jigsaw of sceneries mirrors the changing times.

Moreover, chorographic writing in rural fiction has contributed a new narrative strategy to “object study.” Since the 21st century, many writers’ focus has switched from ancient documents to local life experiences, directing the tradition of object study in classical Chinese literature to regular literature. Taoism’s belief in the equality of all beings and Confucianism’s doctrine of the interconnectedness of all things are, therefore, creatively transformed and innovatively developed.

In chorographic writing, object study means regarding objects and their attributes as the subject of narration. Literature is a study of both humanity and objects. Chorographic writing combines narrative viewpoints, local knowledge as narrative content, and a record-like narrative structure to weave the fictional text. Different generations of writers, such as Mo Yan and Tie Ning who were born in the 1950s, Guan Renshan and A Lai of the 1960s, and Xu Zechen, Fu Xiuying, and Liang Hong of the 1970s, are characterized by different narrative trajectories and spiritual extensions in chorographic writing. Varieties of art forms in 21st-century rural fiction embody the lasting vigor of Chinese culture.

Obviously, chorographic writing should also strive to organically integrate the informative and literary features of rural fiction. Based on experiences and field observations, this approach breaks the limits of previous grand narratives, representing Chinese rural fiction’s unique poetic experiences. Nonetheless, it is essential to strike a balance between the informative nature of local chronicles and the literariness of fiction, and guard against harms to the literary nature of rural fiction. Chinese literature should not only learn from merits of excellent Western works, but also return to its own literary and cultural traditions, thereby opening up new dimensions for creation on the precondition of inheriting traditions of literary chronicles.

Chen Guohe is a professor from the School of Journalism and Culture Communication at Zhongnan University of Economics and Law.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG