Translation pivotal in cross-cultural communication

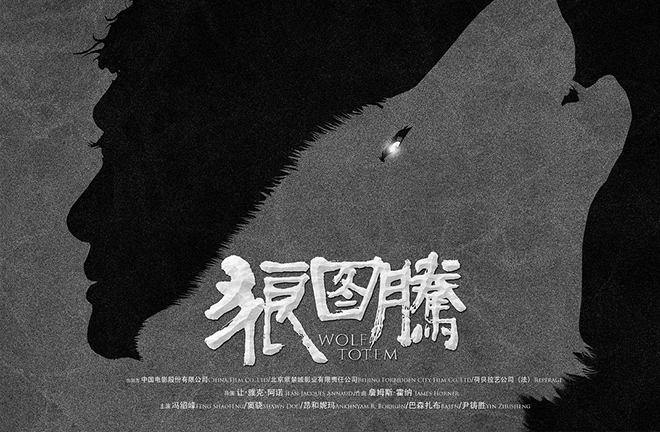

FILE PHOTO: A poster of “Wolf Totem,” a film adapted from the novel of the same name

WUHAN—Hosted by the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Central China Normal University (CCNU) and other institutions, the Sixth CCNU Academic Communication Forum was held in Wuhan, Hubei Province, both online and offline, on Nov. 19. Participating scholars exchanged views on translation and publishing, and the disciplinary construction of publishing science from the perspective of cultural dissemination.

Role of translation

Translation works as a pivotal tool in cross-cultural exchanges. The earliest and perhaps most prolifically translated work of classical Chinese literature introduced abroad is Lao Tuz’s Tao Te Ching. The earliest translation was to Latin, by Francois Noel, the late 17th-century Belgian missionary. According to Du Qinggang, a professor from the School of Foreign Languages and Literature at Wuhan University, Tao Te Ching (including its Latin translation) has been translated and disseminated in France for more than 330 years. In recent years, with the increasing popularity of Chinese philosophy in overseas sinology, the translation, introduction, and research of this classic has presented a diversified landscape.

Liu Lingdi, a professor from the College of Humanities and Law at South China Agricultural University, said that the translation and introduction of Tao Te Ching should not be simply regarded as mere linguistic conversions. These activities are often the crystallization of translators’ research on the work and even the entire philosophy of Taoism. Translators of different eras applied varying translation strategies in the process of introducing this Taoist classic abroad. Variations between versions demonstrate not merely the historical progress of the work’s westward translation, but also limitations at the time, both of which are instructive for today’s better understanding and investigation.

Li Jiajun, an associate professor from the College of Literature and Communication at Hubei Minzu University, said that books of highly academic literary theory found favor among translators in the Republic of China (1912–49). The evolution of literary theory as a discipline has further consolidated the academic basis for the development of modern literature and art. Its publication and dissemination has promoted the modern transformation of traditional literature and the disciplinary construction of modern literature and art.

Two-way cultural communication

“Previous one-way cultural ‘travel’ has become two-way or even multi-way,” said He Weihua, a professor from the School of Foreign Languages at CCNU. Whether to enrich oneself by importing intellectual resources from abroad or to enable Chinese culture to “go abroad” and make greater contributions to mankind, the ultimate goal is to provide more options for the world and to build a better, diversified, and harmonious human society.

According to the copyright trade data released by the National Bureau of Statistics, during the 10 years between 1995 and 2005, the average ratio of copyright imports to exports in China was 10.17:1. By 2016, that number had shrunk to two to one. In the opinion of Zhou Baiyi, director of the editorial department of Jingchu Library, the narrowing ratio is largely attributable to Chinese classics translation projects, and copyright cooperation between publishing houses and countries along the “Belt and Road.”

“As China’s comprehensive strength grows, the cultural imbalance between China and the West will be reversed, and Chinese cultural products will increasingly be introduced into other languages,” He Weihua added. With China’s growing importance on the world stage and the unprecedented prosperity of Chinese culture, its cultural dissemination confidence will continue to grow.

The novel Wolf Totem represents a successful case of copyright export of Chinese books in recent years. The book has been translated into 36 languages and distributed worldwide. It has also been adapted into a film co-produced by China and France. In Zhou’s view, Wolf Totem is a novel about humans and wolves coexisting and conflicting with each other in the grasslands of Inner Mongolia. The Chinese version of the novel has long been on the bestseller list in Chinese mainland, and its Chinese copyright has been sold to 110 countries around the world. Wolf Totem is a truly miraculous example of exporting contemporary Chinese literature to the world.

Publishing history

The modern history of Chinese publishing has witnessed the emergence of a group of national publishing firms, such as the Commercial Press, Zhonghua Book Company, and Kaiming Bookstore. Such organizations have made arduous efforts to pass on and promote national culture and build a spiritual foundation for the people. Fan Jun, director of the Cultural Communication Research Center at CCNU, stressed the importance of inheriting and carrying forward the spirit of the older generation of publishers, such as Zhang Yuanji, Lu Feikui, and Ye Shengtao, who strived for the innovative development and communication of fine traditional Chinese culture.

He Zhaohui, a professor from the Advanced Institute for Confucian Studies at Shandong University, said that since the reform and opening up, Chinese scholars have been actively involved with international academia, and the scope and vision of their research has diverged from their predecessors of 40 to 50 years ago. A great many works on foreign publishing history have been translated and introduced into China, and scholars are increasingly citing foreign references in their studies. A noticeable trend in recent years is that Chinese scholars have begun to expend more effort in researching foreign publishing history and comparative studies between China and foreign countries. This trend represents scholars’ attempts to compile a cross-regional and cross-civilizational publishing history from a comprehensive perspective.

He Zhaohui suggested the necessity of constructing a more integrated global publishing history, which will require abandoning the traditional view of “the other” in world history and of isolation in national history. We need to look at human history as a whole and highlight the rich ties and interactions between regions, civilizations, and countries.

Edited by YANG LANLAN