Translation of Silk Road literature spreads Chinese culture

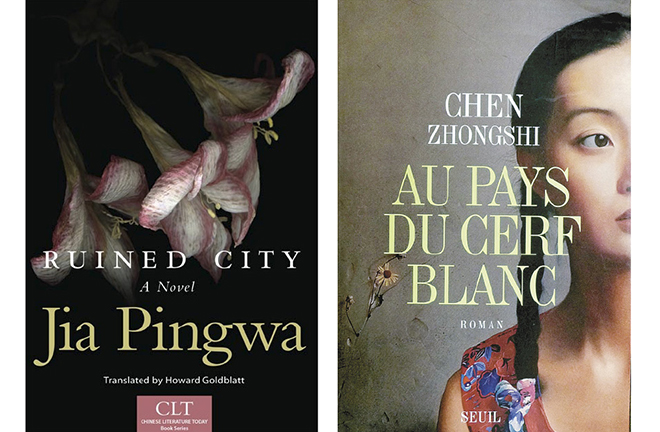

FILE PHOTO: The English edition of Jia Pingwa’s Fei Du, titled "Ruined City" and the French edition of Chen Zhongshi’s Bai Lu Yuan translated as Au Pays Du Cerf Blanc (White Deer Plain)

Silk Road literature [which refers to literary works based on the Silk Road’s historical and regional background] is an important branch of Chinese literature. The translation of Silk Road literature into foreign languages can not only boost the multidimensional implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but will also promote the spirit of the Silk Road and carry forward the Silk Road’s culture overseas.

Translation of Silk Road literature thrives

With the proposal of the BRI and building a human community with a shared future in the 21st century, the landscape of Silk Road literature has embraced a transition in modernity from material transmission to sharing the spirit of the Silk Road. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the translation of literary works on the Silk Road, a substantive symbol of “openness,” has begun to thrive. On the whole, translation of contemporary Silk Road literature focuses on writings about northwest China’s Shaanxi Province, where the Silk Road started; the desert as the route stretched westward; and the borderland where many communities were located.

Works on Shaanxi Province showcase Shaanxi literature’s absorption of the strengths of other regions’ literature, as represented by a cohort of excellent local writers like Lu Yao, Chen Zhongshi, and Jia Pingwa. The rise of the “Shaanxi literary corps” heralded an irresistible trend in the overseas dissemination of contemporary Silk Road literature.

Since 2010, literary pieces depicting Shaanxi, represented by Jia Pingwa’s writings, have successively been translated and spread to the English-speaking world, bringing into being an international communication platform for “northwestern” literature about the Silk Road. Jia’s popular works, namely: Ruined City, The Lantern Bearer, Happy Dreams, and Broken Wings, were translated into English chiefly by renowned Sinologists and published successively from 2016 to 2019.

In May 2018, Jia’s novel The Earthen Gate was jointly translated by Professor Hu Zongfeng, dean of the School of Foreign Languages at Northwestern University; Robin Gilbank, a foreign expert at Northwestern University; and He Longping from Changsha Normal University, creating a translation model featuring cooperation among Chinese and foreign translators.

At the same time, Lu Yao’s novella Life was translated into English by Chloe Estep, a Ph.D. degree-holder in Chinese literature from Princeton University in the US, and was printed in 2019. In April 2020, the English edition was included in Amazon Crossing’s 2020 Free World Book Day Translations and became the first book from China to enter the list. Thereafter Lu Yao saw the first Malaysian edition of his novel The Ordinary World launched in 2021.

The French translation of Chen Zhongshi’s magnum opus White Deer Plain, published by reputed French publisher Les Editions du Seuil in May 2012, was the first Western language translation, following the successive publication of editions in Eastern languages like Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Mongolian. Within less than two months after its debut, more than 3,000 copies of the French edition were sold. The comics version of White Deer Plain was available to readers outside of China in French in 2015.

Starting from Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi Province), the ancient Silk Road stretched westward via Gansu Province and crossed the vast Gobi desert. Xue Mo, a writer from Gansu, rose to fame for his “Desert Trilogy,” which consists of White Tiger Pass, Desert Rites, and Desert Hunters. So far, Xue Mo’s books have been translated into many languages including English, French, German, Russian, and Sanskrit, and published in such countries as the US, Canada, the UK, Germany, Russia, Hungary, Italy, India, and Nepal. The English editions of Desert Rites and Desert Hunters were collaborative translations by renowned American Sinologist Howard Goldblatt and his wife Sylvia Li-chun Lin, printed by the Encyclopedia of China Publishing House in 2018.

As a hub linking the Central Plains and Western Regions, Xinjiang has become a “community for essays” in the Silk Road’s literary landscape. In this community, writer Li Juan has been lauded as the “elf of Altay” for her vivid portrayals of nomadic life and customs in Xinjiang’s Altay, drawing rapt attention from translators and readers abroad. The English editions of her representative works Winter Pasture: One Woman’s Journey with China’s Kazakh Herders and Distant Sunflower Fields were published in February 2021. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese translation of her essay collection Please Sing out Loud When Walking at Night, the Arabic edition of Distant Sunflower Fields, and the French version of Corners of Altay hit the overseas market one after another.

Building international discourse

Viewed historically and globally, vertically and horizontally, the international communication discourse system for Silk Road literature takes the Chinese notion of the “human community with a shared future” as the axis. It upholds openness, dialogue, and integration, centering on the dual landscapes of “natural western China” and the “humanistic Silk Road” to achieve interconnectivity, and underscores the ritual character of ethnic narratives, thus establishing a storytelling-based and ritualized communication path to promote the image of Silk Road literature.

From a generative angle, Silk Road literature consists of literature from the overland and maritime Silk Roads. The two literary types complement and echo each other. Literature from the Maritime Silk Road is composed of literary works along the sea routes in eastern and southern China, including maritime poetry and migration literature [but it has not been fully disseminated abroad through translation].

Based on the situation currently in place for translating Silk Road literature, in the new era, a dual-track mechanism should be built to translate literature for both the overland and maritime Silk Roads. From the perspective of communication, the dual-track translation mechanism highlights the ritual view of communication [as proposed by famed American communication theorist James W. Carey]. It values sharing communication effects to realize identification with communication identities and building a cultural consensus. Through the lens of interpersonal relations in communication, the ritual view advocates for cyclical, two-way communication. Based on communication’s immediate effect, the ritual view emphasizes dialogue and mutual inspiration.

In terms of mediums for translation-based communication of Silk Road literature, interactional mediums for static and dynamic communication should be created. Static communication relies on paper mediums and publication platforms to translate native Chinese Silk Road literary works for readers abroad. The English version of China’s flagship literature magazine People’s Literature, entitled “Pathlight,” was launched in November 2011 under the chief editorship of American translator Eric Abrahamsen. It partnered with Paper Republic, a blog site established in 2007 which gathers a group of Sinologists and young translators passionate about Chinese literature to translate contemporary Chinese literary works for the world.

In 2014, the National Press and Publication Administration of China rolled out a key program to fund the translation of Silk Road literary works. Carried out in the project management model, it supported domestic publishers to export the copyright of Chinese books to neighboring countries and countries along the Belt and Road route.

In 2018, the Foreign Languages Press launched a plan to publish bilingual editions of Silk Road literary works in Chinese and the languages of countries along the Belt and Road, in an effort to build a multilingual digital humanities corpus for Silk Road literature. According to preliminary statistics, more than 2,400 languages are spoken among ethnic groups and in countries along the Belt and Road route, accounting for more than one third of the total number of human languages. Among them, there are a total of 78 official and universal languages, including large language families such as Sino-Tibetan, Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic, Afro-Asiatic [formerly Semito-Hamitic or Hamito-Semitic], Caucasian, and Dravidian.

Based on collecting, organizing, and building multilingual, parallel textual corpuses, it is necessary to increase dynamic mediums for literary communication and actively engage in visual, multimodal corpus construction by integrating images, videos, and animations. Attention should be paid to setting up a multimodal mechanism for the digital communication of ethnic minorities’ living epics, expanding multimodal mediums for communication of written texts, and blending digital communication mediums like pictures and texts, animations, videos, and audios to reproduce the aesthetic and value implications of living epics, with the aid of the multi-image technology of digital media. Efforts are also needed to build an international communication landscape in which Silk Road literary alliances can dialogue and cooperate to spread the spirit of the Chinese Silk Road and its cultural philosophy of peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning, and mutual benefits and win-win results.

Enhancing cooperation in translation

The national awareness and cultural identity of translators, the actors of translation, has a bearing on the effectiveness of Silk Road literature’s international communication. Enhancing cooperation between Chinese and foreign translators and optimizing translation strategies in a holistic manner will boost the export of Silk Road literature in the new era.

Within cooperation between overseas and local translators, foreign translators’ re-narration can provide Western perspectives, while through domestic translators’ self-expressions, we can explore history and reality, which represents an “other” to them, to go beyond unidimensional imaginary others towards multidimensional experiential others, understanding, dialoguing with, and constructing others to gradually transition from cultural communication to cultural self-consciousness.

Therefore, local translators should interpret the domestic creative context of Silk Road literature, while foreign translators assume the task of decoding functional interpretations of Silk Road literature shaped by others, thereby building a narrative system comprising revelation, enlightenment, and immersion. In doing so, we can break through the unidimensional communication vision marked by isolationism and relativism, and acquaint with, complement, and trust each other amid dialogues between various cultural systems to construct a ritualized communication mechanism based on consensus, empathy, and mutual inspiration.

Translation of Silk Road literature in the new era is embedded with a trinity of cultural and value connotations including: the people, the nation, and the world. For the people, individual narratives based on heroic images gradually transition to community-wide civilizational consciousness, thus constructing the national character of local literary discourse with group self-consciousness and strengthening self-identity within communities, while dialoging with world literature to integrate ethnic cultures on the time-honored Silk Road with modern life narratives and inherit Silk Road literature.

Peng Baiyu is from the Translation and Cross-Cultural Studies Center at Xi’an International Studies University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG