Ming, Qing novel illustrations with multiple textual functions

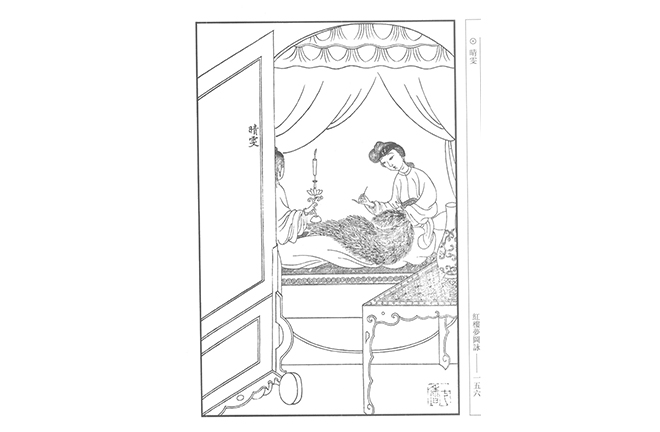

A print of “Skybright mends the cape,” a famous scene from The Dream of the Red Chamber Photo: CFP

Entering the new century, illustrations in ancient fiction, especially in Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) novels, have become a hot research topic. Upon summarizing the origin, form, content, and other basic topics of novel illustrations, scholars have also explored the narrative, criticism, and communication functions of illustrations.

Coexistence

“If the Song Dynasty (960–1279) is the first golden age in the history of printing in China and the world, then the Ming Dynasty can be called the only golden age in the development history of ancient Chinese printmaking,” scholar of Dunhuang studies Bai Huawen wrote in “Tracing the Origins of Ancient Chinese Printmaking.” At the same time, Ming was also a prosperous period for the development of ancient Chinese novels, when novels and illustrations were closely connected and complemented each other.

In Shulin Qinghua [Talk About Books], Ye Dehui noticed that “the ancients were with pictorial books, where there was a book there would be illustrations.” Indeed, especially in the Ming and Qing era, bookshops attached great importance to novel illustrations, which were an integral part of the printing of novels at the time, especially in bookshops. Cheng Chen-to (Zheng Zhenduo) pointed out in Woodcut Brief History of Ancient China that during the Wanli period (1573–1620), “almost no books were without illustrations, no pictures without fine workmanship.” This phenomenon was inherited and furthered in the Qing Dynasty.

In Ming and Qing, the fact that novel illustrations became popular had profound social and historical reasons. According to Cheng Guofu, dean of the College of Liberal Arts at Jinan University in Guangdong Province, the flourishing of novel illustrations derived, on the one hand, from the development of the publishing and printing industry. In the Ming Dynasty, Jianyang, Jinling (present-day Nanjing), Suzhou, and Hangzhou, which were among the major centers of printing novels, were the developed areas of printmaking art. They were called the Jianyang School, Jinling School, Suzhou School, and Hangzhou School in academia. On the other hand, painting art thrived during this period, and many literati and painters had certain changes in their views on novels, especially popular novels. During the Ming and Qing era, many famous painters were involved in the drawing and creation of novel illustrations.

Multiple functions

Illustrations perform an important role in Ming and Qing novels. Cheng Guofu believes that as illustrations of novels, they are intuitive and practical, which helps to deepen the understanding of the text and plot of novels, and better depict the narrative, actions, and personality of characters. In this sense, novel illustrations have the function of a “reading guide.” At the same time, novel illustrations have aesthetic significance. From the printing level, novel illustrations reflect decorative characteristics, which can beautify the book, improve reading interest, reduce reading fatigue, highlight the poetic and pictorial meaning, and enhance the realm of the novel.

However, in the opinion of Chen Wenxin, a professor from the College of Chinese Language and Literature at Wuhan University, illustrations mainly serve the sale of novels, and they represent the positioning of books and readership. They have certain aesthetic and introductory functions, which are derivative, not the primary goal. Illustrations, as paratexts, are part of stylistic construction, and they guide readers’ reading expectations.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, in the fiercely competitive publishing market, illustrations became an instrumental means for bookshops and their owners to publicize and promote their own editions of novels. Cheng Guofu noted that illustrations do have an obvious advertising effect. Compared with the novel edition without illustrations, illustrated books are undoubtedly widely welcomed by readers and the market.

“Literary illustrations illustrate literary works in the way of art, permeating the understanding of certain groups on works,” said Qiao Guanghui, a professor from the School of Humanities at Southeast University, believing that in addition to the traditional functions of embellishment and advertising, illustrations can also embody the characteristics of text acceptance of some groups in a specific period, even their attitude of literary criticism.

According to Wang Yangang, a professor from the College of Liberal Arts at Sichuan Normal University, illustrations of ancient Chinese novels have undergone a process of transformation from story plot illustrations to character illustrations. The illustration modes have also evolved from “illustrations above and texts below” to “illustrations by chapters” and then to “illustrations placed at the beginning of the book.” The different illustration methods are determined by the owners of local bookshops for different readers, and also closely relate to the development of printmaking art and the aesthetic needs of literati.

In a sense, the study of novel illustrations actually investigates the relationship between images and literature, which is a hot topic in domestic literary studies and provides a new vision and method for examining ancient novel illustrations. Qiao and Zhao Xianzhang, a professor from the School of Liberal Arts at Nanjing University, have made active explorations in this field. Qiao believes that the importance of illustrations in literary works has been recognized by the academic community, and theoretical discussions on the relationship between images and texts have been quite complete in recent years. Zhao suggested paying more attention to Chinese traditions and local resources, and to historical depth and the empirical spirit.

Edited by YANG LANLAN