Chinese clans evolving from pre-Qin on

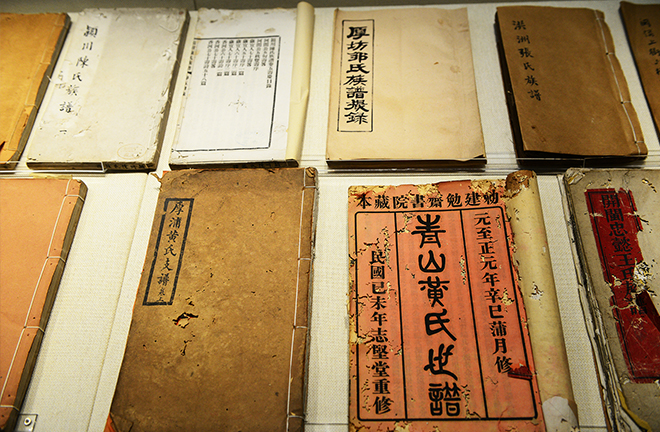

Genealogical documents from different clans, which are on display in Fuzhou Museum, Fujian Province Photo: CFP

As a form of social group or organization, clans (zongzu) have a long history in traditional Chinese society. They also are an important part of modern social structure in China. Over a long evolutionary course, clans presented varying characteristics at different stages.

Foundation

Chinese clans were a product of ancestor worship, the core of which was sacrifice. Clans originally referred to family clusters for sacrificial ceremonies at ancestral temples. In the pre-Qin era (prior to 221 BCE), clans went through three stages, namely the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century–11th century BCE), the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century–771 BCE) and the late Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE), on to the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE).

Clans in the Shang Dynasty were royal kinship groups with multiple sub-clans. Princes of the Shang king, who didn’t succeed to the throne, formed separate lineages together with their descendants, building temples and making sacrificial vessels to worship their own ancestors. According to Zhou Dynasty records, Shang clans were divided into the main lineage (zongshi), lesser lineages (xiaozi), and servants and slaves (leichou). The main lineage was a small family with the primary consort’s eldest son and his wife at the core, and lesser lineages consisted of the families of other sons, who were not entitled to preside over sacrificial ceremonies. The main lineage might bestow upon heads of lesser lineages the power to build an altar for their own parents. Once lesser lineages divorced themselves from the main lineage, they would own their own land and start new cemeteries, and have their own lineage names as new, independent clans. Yet, compared to the “parent” clan they originated from, they remained sub-clans, or branch clans.

In the Western Zhou Dynasty, not all families had surnames. The king enfeoffed subjects, land, and surnames to male royal clan members. Social structure under the enfeoffment system consisted of surnamed lineages, clans, sub-clans, and individual families. Up from the king of Zhou, vassals, high-ranking officials, scholars, down to the common people, blood was the tie which bonded the state in a hierarchical fashion.

The late Spring and Autumn Period saw remarkable changes in social structure, as the feudal system collapsed, making it impossible to sustain clans. The commoners called each other by their lineage names, and surnames lost the function of distinguishing upper and lower classes.

Variations

Clans in the Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (206 BCE–220) dynasties were characterized by continuation from previous dynasties, varied forms, extension of the lineage differentiation system (zongfa zhi) from nobility to the populace, changing functions, and far-reaching impacts. Clan rights (zuquan) developed amid clan leaders’ management of clan members, mutual help within clans, and their self-defense. In terms of ancestor worship and modification of family records or genealogy (jiapu), prominent clans’ activities concerning the selection of officials and marriage were still subject to restrictions imposed by the imperial clan.

The Qin and Han era was marked by transitions and significant changes in clan forms, organizational structures, and clan systems. In the Han Dynasty, in particular, clans were mainly patriarchal, yet supplemented by matriarchy. However, some clan elements from primitive times were retained.

In the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties (220–589), clans were generally structured with three generations of kinship networks under a common ancestor. Every patriarchal family was a clan unit. A clan was a kinship network comprising several clan units. During this period, clans existed as a kind of relationship, instead of as independent entities. Each clan unit was an entity, more like a family. Clans were maintained by genealogy. However, geography was a much more crucial factor. Villages were the foundation for clans to grow. Clans in each village were managed by local networks of fellow villagers and neighbors. Clansmen who entered government service formed clan units around officials. Hereditary aristocracy (shizu or menfa) was a notable phenomenon at the time.

In documents of the Sui (581–618), Tang (618–907), and Five Dynasties (907–960), clans were also termed qinzu (kinship clan) and jiazu (family clan) on different occasions, referring to family unions bonded by blood. The basic organizational structure included a family temple, genealogical documents, ancestral graves, and clan assets.

Apart from the imperial family, eminent clans were scattered, geographically, in Shandong, Guanzhong (modern-day central Shaanxi Province), Lingnan (roughly southern China), and Shuzhong (central Sichuan) and ethnically, in the Xianbei ethnic group, in addition to families with meritorious achievements following the Anshi Rebellion.

Strategic interactions between clans and the state power affected state governance. Cultural traditions of distinguished clans, such as family etiquette, domestic discipline, and family learning, had a bearing on social and historical development. The development of clans was divided into stages such as inheritance, revitalization, reconstruction, and massive integration. Clan organizations had an extensive, deep impact on social cultural life.

The period of the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties was transitional in ancient Chinese history, but representatives and the core values of clans largely came from eminent families. In this stage, clans took more complete, mature organizational and institutional forms.

Transformations

In the Liao (907–1125), Song (960–1279), Xixia (1038–1227), Jin (1115–1234) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties, the evolution of clans varied from region to region. Clans under the rule of the Liao, Xixia, and Jin regimes mostly carried forward philosophies and organizational models from the hereditary aristocracy system.

In the Song Dynasty, clans within the sovereignty of the Southern Song in particular, were transformed towards jingzong shouzu, literally venerating the eldest son of the primary consort for he held the power of leading ancestor worship, who meanwhile strived to foster cohesion among clansmen. The upper class in the Liao, Xixia, and Jin eras were dominated by eminent families, which had a big role to play in political, economic, cultural, and social life.

Clans of nomads and farmers, due to their different modes of production, lifestyles, and evolved social forms, were organized in markedly different models. The organizational structure of nomadic clans was very complicated. Heads of the clans were not only charged with keeping internal order but would also actively participate in affairs of social organizations at various levels, such as tribes. By comparison, members of agricultural clans featured tenants’ heavy reliance on landowners.

Within the areas governed by the Northern and Southern Song courts, the transformation of the hereditary aristocracy system, typical of the Wei, Jin, Sui, and Tang dynasties, into the jingzong shouzu system in the Song Dynasty resulted from reforms in social and economic relations during Tang and Song times, and from scholar-officials’ endeavors to maintain their high status. The Song’s clan system was adapted to social conditions specific to the later stage of traditional Chinese society, playing an important role in coordinating relations between classes, and maintaining social stability.

In the Yuan Dynasty, the jingzong shouzu system steadily improved, while showing regional disparities between the south and the north. The great reunification of China, accomplished by the Yuan Empire, led to a relatively stable social environment which facilitated frequent flows and exchanges among ethnic groups in north China. The organizational model of clans, among northern ethnic groups migrating southward, was subject to the influence of the Han ethnic group. Clans in north China developed further from their existence in the Northern Song Dynasty, as their group consciousness and cohesion both grew.

The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) witnessed vibrant construction of clans, which gave rise to new forms and a myriad of advanced ancestor worship practices. Village compacts (xiangyue) were implemented among clans and genealogy’s form matured. Building memorial temples to worship distant ancestors was partly legitimized, with genealogical records compiled to include extended ancestry, which enlarged and made clans organized, and enhanced their cohesion, influenceing daily lives, cultivating new clan communities, and reshaping social structure. Clan building by scholar-officials in the Ming Dynasty resulted in many privileged families and great clans. They constituted the backbone of society, reforming customs to morally enhance society.

Regarding social attributes, clans in the Ming Dynasty generally advocated for traditional orthodox views, engaging in social construction by trying to abandon old, bad practices. Contributing to good social order in the Ming era, these social groups and organizations adapted to social developments and changes to some extent. The so-called modern Chinese clan form took shape during this period, when clans were a social force that none could afford to overlook.

In the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), clans developed in four stages. During the reigns of the Shunzhi and Kangxi emperors, the clan system was incomplete and thus clans were inactive. When the Yongzheng, Qianlong, Jiaqing, and Daoguang emperors held the throne, kinship groups thrived, tying in closely with a series of government policies. Clans, ancestral halls, and ancestor worship were popularized alongside a maturing style of genealogy, complemented by the community self-defense (baojia) system and the village compact system to form a social network at the primary level. Under the rules of the Xianfeng, Tongzhi, and Guangxu emperors, clans in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, were disrupted by the Taiping Rebellion, but they quickly recovered. Government control over clans weakened with the decline of the Qing court. During the Guangxu and Xuantong emperors’ reigns, clan associations (zuhui) emerged out of elections by clan members, which oriented clans towards modern democratic autonomous organizations.

The development of clans in the Qing Dynasty showed four characteristics. First, clans were universal and autonomous. Second, the traditional patriarchal system still functioned in everyday life but was weakening and evolving into a democratic system. Third, clans collaborated with political power to indoctrinate the populace, with the former relying on the latter. Fourth, the development of clans was imbalanced across regions and to varying degrees during different periods. In general, clans were prevalent in folk society in the Qing era. They were democratic, autonomous, and cooperative, among other social features.

In the 20th century, clans were severely impacted by drastically changing social forms, as they reformed themselves and adapted to the changes. Clan forms became increasingly diverse and ultimately evolved into clan associations.

As a key component of Chinese society, clans are continuously adjusting to social developments and changes, and developing into modern social groups.

Chang Jianhua is a professor of social history at Nankai University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG