Confucianism has global and contemporary relevance

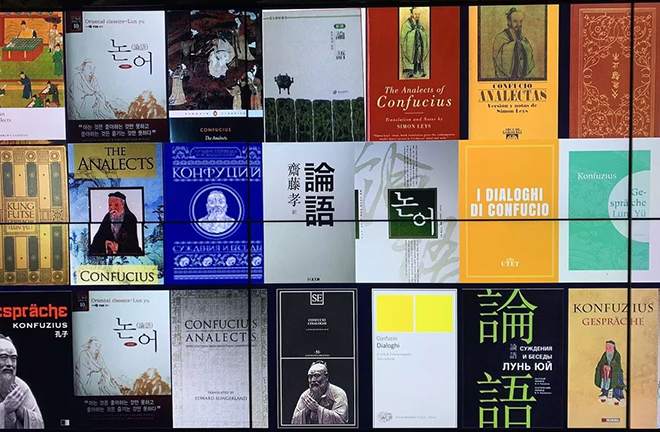

FILE PHOTO: A screen at the Confucius Museum in Qufu, east China’s Shandong Province, displays the covers of various language editions of Confucian classics.

Historical life and contemporary existence form a continuum. The continuum renews ancient wisdom and reconstructs ancient cultures in its own way to usher in the future world. This is the point of departure for us to re-explore the global significance and contemporary value of Confucianism.

Contemporary relevance

In modern times, empiricism and rationalism were strong foundations of thought for Britain and France as they revived Aristotelianism and Platonism. In Germany that rose thereafter, classical philosophy became the source of thought as well as a spiritual power.

On the world stage, the US shines for its strength in education, science and technology, economic development, and military, but the covert impetus for thinking has been pragmatism founded by Charles Sanders Peirce and developed by William James and John Dewey. This genuinely indigenous philosophy has shaped the US spirit and culture.

In the long history of ancient Chinese philosophy, diverse thoughts of the Pre-Qin period (prior to 221 BCE) carry the most cosmopolitan genes. Therefore, it is vital to go back to the Pre-Qin era to examine the Hundred Schools of Thought and their doctrines in depth, thus advancing the development of philosophy and social sciences with Chinese characteristics and promoting fine traditional Chinese culture.

Confucianism as a system

Among the myriad thoughts of the Pre-Qin era, Confucianism is a philosophy that one cannot afford to avoid. Chinese philosopher Wei Cheng-tung (Wei Zhengtong) said that Confucius was the most representative figure among personages of his previous and later generations, because he went very deep into problems of that time. He might not always handle every issue better or more effectively than others, but no one paid attention to holistic issues like him, Wei said. None of the thinkers of his later generations were not subject to his influence, whether they agreed or disagreed with his views. The focus of praise and criticism was all on him, which is enough to prove that he had been in the central position in the history of thought and was the representative of cultural thoughts.

Renowned German philosopher Karl Jaspers juxtaposed Confucius with Socrates, Buddha, and Jesus, honoring the four great minds as “paradigmatic individuals.” “In the troubled times following the disintegration of the Empire, Confucius was one of the many wandering philosophers who aspired to save the country with their counsels. All found the way in knowledge, Confucius in knowledge of antiquity. His fundamental questions were: What is the old? How can we make it our own? How can we make it a reality?” Jaspers said. Confucius devoted his mortal life to seeking answers to the three questions, striving to translate tradition into conscious principles and thereby give rise to a new philosophy which identifies itself with the old.

Confucius left no writings. His sayings and ideas on delivering ancient voices and reconstructing ancient culture were recorded by his disciples. After his death, many virtuous and wise men pooled their strength to create the text of The Analects that consists of orderly chapters and passages, so that Confucius’s profound and practical teachings and thoughts can interpret themselves in rigorous logic.

The Analects bears Confucius’s aspiration to reconstruct ancient culture and save the country with wisdom. Starting from men’s similar human natures yet vastly different practices, he examined history perseveringly, discovered a retrospective yet groundbreaking outlook on the development of history, and explored the paths of cultivating benevolence (ren), practicing the proprieties (li), and deriving pleasure. On the national level, he founded a moral philosophy for reconstructing antiquity; regarding individuals, he put forward the gentleman (junzi) theory that prioritizes virtues.

In short, Confucianism is a system. The proposition on humanity that “by nature, men are nearly alike; by practice, they get to be wide apart” in The Analects is the cornerstone of his teachings; the trailblazing outlook on historical development brought into being a universally applicable historical philosophy; the doctrine on benevolence is his moral philosophy while his views on rites (another connotation of li) constitute his political philosophy. Learning to help oneself and others grow is his education theory; the golden mean (zhongyong) is not only his moral code, but also the methodology for gentlemen to help themselves and others succeed; and his life philosophy is to derive pleasure from “letting the will be set on the path of duty, letting every attainment in what is good be firmly grasped, letting perfect virtue be accorded with, and letting relaxation and enjoyment be found in the polite arts,” The Analects read.

Lofty status in human civilization

Confucianism, which has created a paradigm of thinking for humankind, is a collection, a pivot, and a tradition. First, from legends of remote antiquity to the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties (c. 2070 BCE–256 BCE), Chinese ancestors gradually established a cognitive framework of human relations and ethics, characterized by the basis of the Way of Heaven (tiandao), the goal of benevolent governance (renzheng), and the means of people-centered administration (mindao).

Into the Spring and Autumn Period (770 BCE–476 BCE), the turmoil caused by the disintegration of political units catalyzed the liberal development of the immature cognitive framework, heralding the heyday of the contention among the Hundred Schools of Thought. Believing in and loving the ancients, Confucius thirstily quested for genuine knowledge from history, delivering voices of antiquity and reconstructing ancient culture in a retrospective yet groundbreaking fashion. In this regard, Confucianism is a collection.

Moreover, observing a pioneering historical outlook, Confucius analyzed the merits and demerits of ancient civilizations, and absorbed the thought of the 7th-century philosopher and statesman Guan Zhong, exploring benevolent and wise ways to enrich the people and bring prosperity to the country by combining rites and punishment. In doing so, he not only influenced later Mohism, the doctrines of Yangzi and Zhuangzi, and the theory of punishment and award in Legalism, but also inspired Zizhang, Zixia, Zengzi, Simeng, and Xunzi to develop their own philosophies. From this perspective, Confucianism is a pivot for other schools of thought.

Finally, Confucius sought a path to save the nation with wisdom through the integration of benevolence into propriety, creating a moral philosophy and gentleman theory from national and individual dimensions, and helping bring to maturity the Chinese philosophical ethics and moral civilization that originated from remote antiquity.

“This position and influence of Confucius are to be ascribed, I conceive, chiefly to two causes: his being the preserver, namely of the monuments of antiquity, and the exemplifier and expounder of the maxims of the golden age of China; and the devotion to him of his immediate disciples and their early followers,” said Scottish Sinologist James Legge in The Chinese Classics. “The national and the personal are thus blended in him, each in its highest degree of excellence. He was a Chinese of the Chinese; he is also represented as, and all now believe him to have been, the beau ideal of humanity in its best and noblest state.”

The way found out by Confucius to achieve the best and noblest state of humanity is to foster benevolence and learn about propriety earnestly, studiously, and virtuously, thus becoming men of integrity featuring letters (wen), ethics (xing), devotion of soul (zhong), and truthfulness (xin). To oneself, he must be virtuous, wise, and bold, while to others, he must be civilized and then gentle. When serving society, “he who is not in any particular office has nothing to do with plans for the administration of its duties,” according to The Analects.

Furthermore, he put forward two principles for building a well-ordered society. “First, a capable man must stand in the right place, and second, the political conditions must be such as to make effective action possible,” Jaspers said.

In Confucius: Secular as Sacred, American philosopher Herbert Fingarette described Confucius as a great cultural innovator rather than as a genteel but stubbornly nostalgic apologist of the status quo ante. “Confucius’s teachings transformed the concepts of li and other virtues, the conception of human society and its possibilities; he created a new human ideal.”

Fingarette continued, “Only as we grow up genuinely shaped, through and through, by traditional ways can we be human; only as we reanimate this tradition where new circumstances render it otiose can we preserve integrity and direction in our life. Shared tradition brings men together, enables them to be men. Every abandonment of tradition is a separation of men. Every authentic reanimation of tradition is a reuniting of men.”

American political philosopher George Holland Sabine noted that “political theory is, quite simply, man’s attempts to consciously understand and solve the problems of his group life and organization.” Among other problems, the most fundamental one is how people should be together.

In Confucius’s view, this issue not only means how the monarch and his subjects should be together, but also how officials and civilians should be together, even how families and friends should be together. These problems must be solved in a political manner.

Confucius’s contribution to humankind is that he crafted social schemes on how people should be together from learning to improve themselves to learning to help others, further to exercising government by means of his virtue, serving his prince according to what is right, and in such aspects as sincerity (cheng), reverence (jing), truthfulness, and righteousness (yi). In the meantime, he offered a basis, reasons from political perspectives, and existentialist principles for the theory of human nature. This is the reason why Confucianism can generate lasting and ever stronger global influence beyond time and space.

Tang Daixing is a distinguished professor of philosophy at Sichuan Normal University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE