Mineral resources to be adjusted for low-carbon growth

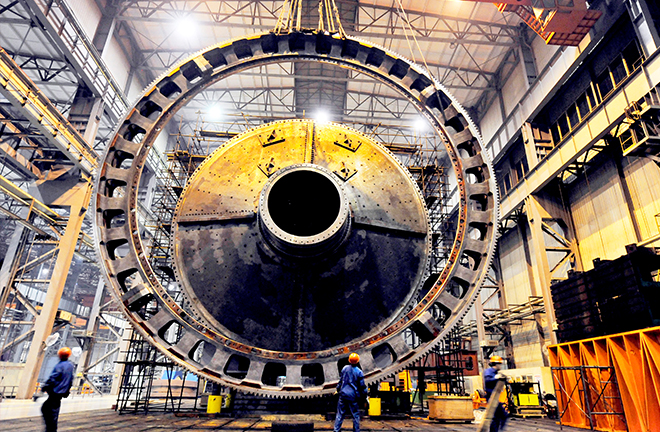

The largest-scaled and most complete semi-automatic ore grinding mill for the mineral molybdenum, a type of ore sourced in China. Photo: Huang Zhengwei/CNSphoto

Today, the world is blighted by a widening global gap of carbon emissions reduction, and a deficit of climate governance. In the General Debate of the 75th Session of the General Assembly of the UN, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China would scale up its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions by adopting more vigorous policies and measures. It aims to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.

In the critical juncture when countries are dedicating themselves to fighting against the pandemic, and facilitating economic recovery, China proposed such a grand goal to tackle climate change. The decision shows its resolution in practicing the green low-carbon concept while shouldering its international responsibility.

Emission problems remain persistent

Vigorously advancing ecological progress in recent years, China has made the decline of carbon dioxide emissions per GDP a binding index to measure national and local development. By fostering the building of carbon markets, and increasing carbon sink, China has yielded considerable results in this sector. By the end of 2019, China’s carbon intensity fell by about 48.1% compared with 2005, and attained its previous target set to the public that a decrease of 40%-45% should be achieved by 2020. By the end of the same year, the proportion of non-fossil energy consumption in the whole of energy consumption reached 15.3%, which was 7.9 percentage points higher compared with 2005; the forest areas and forest stock volume in 2008 increased by 45.09 million hectares and 5.104 billion cubic meters respectively, which made China the country with the largest growth of forest resources in the world in the concurrent period.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that as a country with large amounts of fossil fuel energy consumption such as coal and petroleum consumption, China is still impinged on by problems of environmental pollution and greenhouse gas emission caused by traditional energy. This is difficult to resolve by merely end-of-pipe governance (any system that processes waste before discharging it to the environment, including waste burning, recycling, and chemical treatment).Other profound adjustments in such sectors as industrial, energy, land use, and transportation structures need to be made.

Pressure of strategic minerals’ supply

Strategic minerals can be regarded as important materials which underpin the transformation of energy. Today, a new round of green low-carbon revolution marked by the shift from fossil fuel energy to renewable energy is sweeping across China, and such transformation is largely dependent on strategic minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and tombarthite.

Looking to the world, it now faces great changes unseen in a century, which increasingly complicates the competition within the international market of strategic minerals. In view of this, the security of strategic minerals is challenged by complex risks and uncertainties.

On one hand, international conflicts are increasingly caused by geographical, political, and economic attributes related to natural resources, which has posed potential unsteadiness to the supply of strategic minerals. Driven by global sustainable development and energy transformation, many countries have growing misgivings about such strategic minerals which are scarce in their supply.

On the other hand, as China phases into a new stage of ecological progress, there are more limitations set in terms of resource exploitation. In this context, the domestic mineral exploitation thus shrinks in China, which further increases the country’s dependence on international mining products and the pressure of minerals supply.

International participation needed

For China to ease the situation, all the links ranging from the exploration, mining, smelting, processing, utilization, recycling, to storage of strategic minerals should be well interconnected with each other to ensure the supply of the minerals and a resilient supply chain.

It is also important that China participates in the reform of the global mineral system and environmental governance system and optimize the allocation of its minerals around the world. In addition, it is necessary to further bolster cooperative ties with countries along the route of the Belt and Road (B&R) initiative regarding resource exploitation, trade, and division of labor, which is mutually beneficial.

Considering future trends, the guarantee of minerals must transcend beyond the market supply which targets volumes, scales, and costs. As global minerals have infiltrated into the domain of geo-politics with rising uncertainties, countries’ competition in resource markets has actually turned to a contest of industrial policies. Reflecting on the relationship between the state and the market, industrial policies can influence international trade and the world economy by producing invisible “strategic interaction” between countries.

For a long time, the international energy resources and mineral product markets have utilized the US dollar as the settlement currency, which makes the US dollar index closely related to resource prices. It thus means a high cost of maintaining the stability of the strategic mineral supply chain. In view of this, it is necessary to lower the cost by means of green finance and innovative policy tools.

Wu Qiaosheng and Cheng Jinhua are professors from the School of Economics and Management at China University of Geosciences.

Edited by BAI LE

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE