Traditional law needs adaptation for modern society

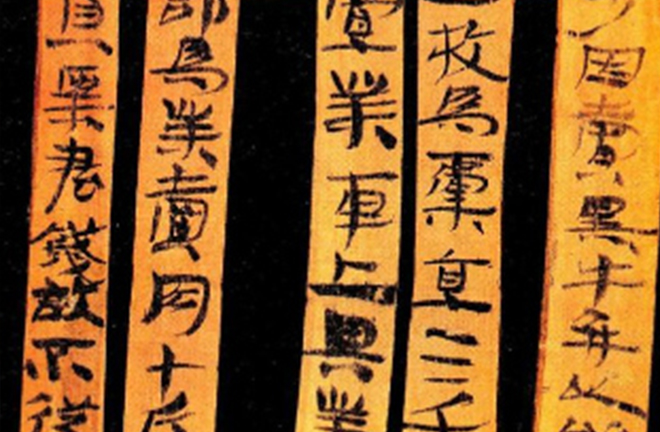

The above-pictured bamboo slips, dating to the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE), keep record of codes and ordinances carried out at that time. Photo: FILE

Traditional law is a dispute settlement mechanism based on the society of acquaintances, blood-tied kinship networks, permanent residents, and small-scale farming communities. In recent years, more and more scholars have reviewed classical documents centered on Confucianism to illustrate the applicability of traditional law, demonstrating its internal logic and ability to adapt to the complications of local society. Generally they argue that traditional law is still completely applicable and complementary to modern society.

However, a deeper study of legal theories that value ethics and rites would reveal that these scholars usually overlook the differences between China's governance in ancient and modern times. Scholars oversimplify the issue, reducing it to a conversation about human nature's constancy or the sanctity of classics, while ignoring the divergence between modern governance needs and the written context of ancient texts.

Their arguments are flawed primarily because they neglect the complexity of information in modern times, the evolution of production models and lifestyles, and the transformation of modern societies on community levels. Traditional law undeniably has a wealth of referential resources, but many classical legal studies have long been confined to mutual recognition within academia. It is hard to translate these into valuable resources for modern rule of law. Problems within traditional law need deeper reflection.

Complex information

Traditional law usually relies on the discourse power of classical literature, while overlooking the modern demographic structure's transition and new information processing mechanisms. The conventional arbitration system’s emphasis, from the Pre-Qin Era (prior to 221 BCE) to the late Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), ranges from specific community-level disputes to the integrated formulation of legal codes, as well as patriarchs’ subjective judgment and experiences grounded upon feudal ethical codes.

Wu Shuchen, a professor of law at Shandong University, agreed that traditional law regards rites as the law, emphasizes traditional codes of conduct, prioritizes moral standards over penalty, and tries to reduce conflict.

Therefore, traditional law results from differentiated mediation by arbitrators within a small jurisdiction, based on their knowledge of each individual and each person's morality. Moreover, settlement of many common disputes is ceded to the clan patriarch. In this light, the basic elements for traditional law to function include the belief in kinship as a natural arbitration power, limited jurisdiction, and a long-term fixed population.

In this governance context, a host of classical documents which preceded the codes and ordinances of the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE) became principles for later generations to deal with community-level affairs. Their legal theory assumed that the power of patriarchs was absolute, as was cooperation among his subordinates. Hence traditional legal thought can be attributed to the concrete governance structure rather than nationalism or cultural determinism.

If the effectiveness of traditional legal thought is based on a stable agricultural society and agricultural cooperation is placed within a framework of kinship, then population migration and transregional communication are essential to modern society.

With the population flow in modern times, laws will necessarily shift their focus to process intricate, varied, and changing information through legal mechanisms. The ability to collect, classify, code, and store complex information is always vital in various aspects.

Therefore, traditional law differs from modern law fundamentally in the evolution of information acquisition and processing. Individuals' social identities in the traditional context were restricted by blood relations and local customs. Meanwhile, in the modern era, social identity and lifestyle have been released from traditional living environments and community expectations. Particularly in the information age, we cannot escape from the dynamic projection of institutional and societal complexity of global cultural systems onto different individuals.

From ancient to modern times, the depth and boundaries of state governance depends on the degree to which citizens’ information is grasped and handled. However, traditional legal discourse features classical determinism, always seeks certainty, and adheres to essentialism. Boiled down to fundamentals, information that would shape the law is regarded as static. Since community information is considered eternal and unchanging, the resultant law becomes static, too. Consequently, the law cannot adjust to a changing modern society and may even invite social backlash.

Governance of nationals

One of the merits of traditional law is the emphasis on rule of virtue and moral discipline. However, scholars generally disregard the transformation of national governance in modern times. On the one hand, scholars have to admit that modern state law has divorced from morality, and accept diverse moral outlooks unless some immoral behaviors are legislated. On the other hand, with a prolific population and a stronger consciousness of rights, modern law pursues high levels of efficiency in arbitration. Traditional law with its consistent pursuit of rule of virtue is obviously unable to handle the new situation.

Looking back at the enfeoffment and clan system in the Pre-Qin period and the following period of long-term community-level autonomy, steering individual characters back into social order was successful because arbitrators had absolute control of information about each individual in the small population and closed jurisdiction.

As populations migrated and information became increasingly complex, the mobile society became marked by a lack of identification and a simplification of formerly diverse criteria for evaluating individual characters. The ultimate criterion was to obey public rules, and as an actual effect, state policies and laws would replace education to assess individual characters.

From the perspective of modernity, Anthony Giddens described the modernization of the state as the separation of individuals from regional restrictions to directly face the four institutional dimensions of modernity: "heightened surveillance, capitalistic enterprise, industrial production, and the centralized control of the means of violence."

This prompts the reflection that modernization proceeds with the emancipation of the population from land and regional restrictions as individual and national codes of conduct align. The unification of national taxation policies is, in essence, for the sake of developing a commodity economy, while highly intensive administrative control and the statistical ability to provide citizens' information will integrate populations from different regions organically. In that case, related legal theories will inevitably be an outcome of the new type of state governance and order, and individuals who break away from small communities have fundamentally been incompatible with traditional law.

Changes in community-level society

Traditional law centers on community-level patriarchal clan systems and respects kinship. Relevant studies are tilted towards demonstrating the superiority of small communities and usually pin hopes on restoring rural order through the model of governance by village gentry (xiangxian), neglecting the evolution of modern states, and the ways they control resources and individuals.

Indian historian and Sinologist Prasenjit Duara's state involution theory has effectively revealed the crisis in modern governance. This is a crisis of contradiction, as the state hopes to rely on old systems, or prop up agents to extract resources for building modern police, educational systems, and developing modern military while resources are being continuously consumed by intermediate levels in the hierarchy. American Sinologist Philip Alden Kuhn also pointed out the conflict of population growth and free land market expansion in the late-Qing Dynasty with rising costs for the government to function.

This means that the root cause of disorder in modern times doesn't lie in moral crisis, or a belief in feudal ethical codes, but in the split between modern state governance and the original structure of governing power. The traditional law problem is not simply about the selection of a concept or a culture. Instead, it concerns a social structure.

If traditional judiciary stresses mediation and largely depends on judges' interpersonal skills and familiarity with local language, customs, culture and social background, then the development of modern society has homogenized different cities and communities. Local networks no longer cause pressure on the judiciary as traditional society did.

Sociological research carried out by Chen Bofeng, a professor of law at the Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, has made it clear that communities in China have generally been stratified with divided interests. There is no homogenous civil society in urban communities to accommodate folk law, and rural society cannot be summarized as an ideal model for the society of acquaintances. Therefore, the theoretical foundation of traditional law is weakening.

It can be seen that the operational model of community-level society in modern times is entirely different from the classical rural order envisaged by Confucianism. As such, the traditional law crisis (starting from the late-Qing Dynasty) doesn't result from the culture movement in modern times. It is imperative to reexamine the long-term evolution of culture and law since the mid-Qing Dynasty, particularly changes in the dispute settlement power following population movement and in subordinate relationships, alongside the underlying transfer towards resource extraction and production models.

If the context of traditional law was established upon ceding covert governing power, entitling patriarchs to aid the state in taxation and governance and accordingly granting them arbitration rights and discourse power via feudal ethical codes, then modern law is a result of modern states' direct takeover of citizens. Traditional legal discourse ignores the invalidation of legal principles caused by changes in the structure of governing power. It is urgent to face the problems listed above.

Wang Chenguang is an associate professor and deputy dean of the Department of Philosophy at Xidian University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE