Ba Jin: Man who lit a torch in darkness

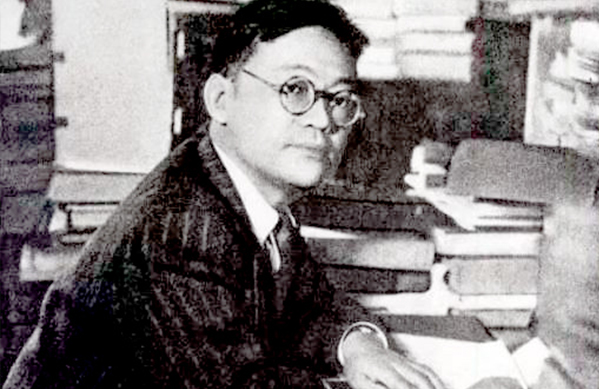

Ba Jin in his youth Photo FILE

From age 28 to 42, the Chinese writer Ba Jin lived his prime years in wartime. During this period of great turmoil, he wrote Fire, a trilogy about the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, and Chun (Spring) and Qiu (Autumn), the last two volumes of the autobiographical trilogy Jiliu (Torrent). When the nation was in peril, Ba Jin did what he could do as a writer and looked forward to the rebirth of the nation.

From fire to Fire

Fires may have scorched Ba Jin his entire life.

On Jan. 28, 1932, the Japanese army attacked Shanghai and the Chinese army stationed in Shanghai rose up in resistance. A few days later, Ba Jin returned to Shanghai from Nanjing. When the ship arrived at Shanghai, the first thing he saw was raging fires and dense smoke. “I stood on deck and looked up at the sky. The sky in the north was blanketed in thick, black smoke, and the smoke was floating towards the south, layer upon layer, almost enshrouding the entire sky. Cannons were thundering, machine guns rattling, and many people were screaming...Shanghai was burning!” (see From Nanjing to Shanghai).

Ba Jin couldn’t go back to his residence, where the Chinese soldiers were engaged in a fierce firefight with the Japanese invaders. He was made homeless. “I knew my residence and all my books were in Japanese hands… After that I walked the lonely streets and slept over in my friends’ houses” (see preface to A Dream of the Sea). Ba Jin suffered deep humiliation during those dark days. On seeing how the war trampled over freedom and lives, he began to think beyond his original beliefs.

Five years later, Ba Jin saw Shanghai in flames again (the Battle of Shanghai which took place between Japanese and Chinese troops in 1937, was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression). The city was groaning with pain again: “Homes are burnt to ashes, lives destroyed and land scorched. In front of me is a raging inferno. I have never seen a fire like this. It destroys everything: life, work, property and hope…It is the land where I live that is burning; It is my countrymen and siblings who are suffering; It is my hopes and dreams that have been shattered. The ideal of the nation is in torment” (see Fire).

Like many other writers, Ba Jin’s most important weapon was his pen. He finished Fire during wartime. Though considering this work a failure in terms of art, Ba Jin never regretted writing it. According to him, he wrote it to express passion, release anger and sorrow, strengthen belief and search for the hope of the nation.

From ‘never die’ to ‘new life”’

From November 1937 to December 1941, a period of Japanese invasion, the neutral Shanghai International Settlement became a gudao (lone islet) of safety from the savagery of the Japanese soldiers. Works created by a group of intellectuals living in the international settlement became known as “Gudao Wenxue,” or “Lone Islet Literature.” Ba Jin was in the “lone islet” for two years, during which time he wrote the two novels Chun (Spring) and Qiu (Autumn).

Some questioned Ba Jin for not depicting the war directly but writing instead about an old family at such a special time. The writer had his own purposes. “‘Everything is about the war!’ This is what people have been talking about, but I’d like to take it a bit further: What should we do after the war? We should fight against feudalism during and after the war. The ghost of Master Gao [a character in the trilogy Jiliu, a representative of conservatism and feudalism] has been lingering around me over all these years. When writing Qiu, I found myself in the thick of a desperate fight against that rotten system” (see On Jiliu). This idea is also connected with Ba Jin’s unique view of the war. He said that the war was not only about winning but also a chance for the Chinese nation to wake up and gain a new life. Ba Jin believed that only a “social revolution” could save the nation: “I’ve never doubted the road of ‘anti-X’ and I believe that it is our way out currently. So far as I know, the road that the masses choose contains the fight for freedom… However, this road can’t be simply generalized as ‘anti-X.’ We cannot solve the problem by proposing ‘anti-X’ thought without thinking about what to do afterwards. If ‘anti-X’ action was a door, we would have to first step through this door, so as to walk to freedom, survival and light. It’s time to prepare for what to do after we step through the door, as there is still a long way ahead. None of us are patriots in a narrow sense. In recent years, the European continent has given us many useful examples” (see Road).

With the belief that “the motherland will never perish,” Ba Jin was thinking about how to bring new life to the old nation through a war of resistance and reform.

Little People, Little Events

In the summer of 1941, Ba Jin lived in a bookstore in the Shapingba district in Chongqing (a southwestern city that served as a capital from 1937 to 1946). His friend Tian Yiwen recalled that in a starkly furnished room, Ba Jin sat in front of a square table near the window and wrote. “Ba Jin didn’t have the habits that writers normally had. He didn’t smoke and drink tea. In front of him was only a cup of water and a stack of paper.” “He kept writing and didn’t sleep until the dead of night.” However, this was no paradise. “In early summer, the weather in Shapingba was terribly hot, and the region was infested with bugs and rats, which was even more terrifying,” Tian said.

Ba Jin later wrote about his life in Shapingba in the novel Huanhun Cao (Resurrection Grass). From this novel onward, his writing style started to change. Later he explained, “I published a short story collection titled Xiaoren Xiaoshi (Little People, Little Events) during the 1940s. I admire ordinary people and their daily stories.” Ba Jin’s focus shift from “heroic epic” to “little people and little events” had something to do with his wartime experience. Just as he said, “I always believe that the fundamental power of the Chinese nation is derived from these ordinary people. The reason why the Chinese nation is never overwhelmed by difficulties and disasters lies in our people, not in the few who wear red flowers [people of exemplary behavior]. I started to explore the source of the power of our nation, and wrote about a series of ‘little people and little events’” (see On Resurrection Grass). During the late stage of the war, Ba Jin attached more importance to ordinary people and their ideals. Therefore, in his novel Disi Bingshi (Ward No. 4, a novel set in a hospital in rural China during World War II, a haunting window into the isolation and displacement faced by ordinary citizens), Ba Jin portrayed a female doctor who “is not a shining heroine” but merely a young doctor, who brings warmth and happiness to others.

During those turbulent years, Ba Jin kept writing to support the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. In Wenxue Shenghuo Wushinian (Fifty Years of Literary Life), he wrote, “Every time I made a simple ‘nest’ for myself in a city, I was forced to leave the city empty-handed, except with a few pieces of paper. In those days, I had to run around and change my ways of writing. It was hard to get ink in some places. When working on the novel Qiyuan (Garden of Repose), I usually took an ink stick, a writing brush and a stack of paper in my bag… It reminds me of how Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol wrote in small hotels. Just like him, I wrote while wandering from place to place, from the hotel in Guiyang (a city in Guizhou Province) to Chongqing. One night, I was working on the end of Qiyuan in a small hotel in Chongqing. The bulb was not bright, so I lit a short candle. The candle oil ran out before the writing was finished. How I wished I could have had another candle to keep writing…”

The article was edited and translated from Guangming Daily. Zhou Limin is the executive vice president of the Association of Research on Ba Jin.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE