Anti-epidemic measures in ancient China

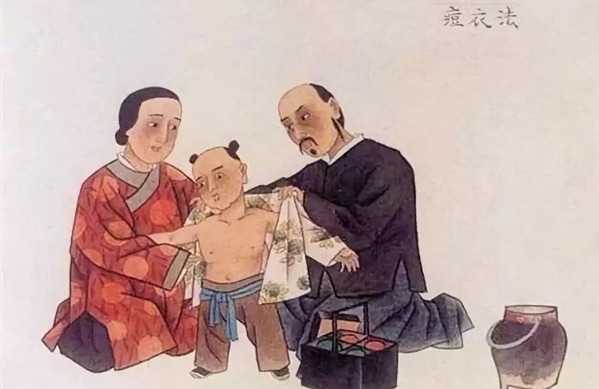

Douyi fa (literally, pox-garment method), an early practice of smallpox inoculation in China, involved dressing a child who had never been infected in the clothes from an infected child. Photo: FILE

One of the greatest medical advances in human history, the vaccine is made of a virus, bacterium or other microorganisms, administered primarily to prevent disease. Ideas and practices similar to the use of vaccines have been in China since a very early time.

Fight fire with fire

In ancient China, diseases were generally called ji yi, in which ji referred to common, non-communicable diseases, while yi referred to communicable diseases or plagues. This classification is similar to that of modern scientific medicine. The WHO has listed the 48 most lethal diseases, 40 of which are communicable diseases. Compared with ji, yi is more dangerous to humans. Any large epidemic outbreak can be devastating. In China’s recorded history, people have frequently suffered epidemics of disease ever since the Shang Dynasty, recording over 500 significant outbreaks. Literature has provided terrifying accounts of these epidemics, such as describing the dead lying unburied and an eerie silence across the land.

During battles against epidemics, people gradually developed a way to prevent disease through administering limited exposure to the disease-causing microbe, which could stimulate immunity against the disease. In the philosophical treatise Lun Heng (Discourses on Balance), Wang Chong (c. 27–97), one of the most original and independent thinkers of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), proposed to cure a patient with the disease-causing object or something similar to it, an idea further explained in his book as “the disease caused by wind invasion should be cured by wind; the one caused by heat should be cured by heat” (the pernicious influence of wind and heat is considered one of the major causes of illness in traditional Chinese patterns of disharmony). This idea is commonly known as “yi du gong du” (literally, to combat poison with poison, a saying similar to “fight fire with fire”). The earliest reference to this idea is in the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon), the earliest written work of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which believes that some of the treatments used in TCM won’t be effective unless they contain potentially damaging components.

Although the ancient Chinese had too little knowledge of diseases to come up with science-based health measures, the idea of yi du gong du is to some extent consistent with modern medicine. In addition to humans’ innate immunity, humans are able to acquire a new defense system when their primary immune response is initiated, resulting from exposure to an actual pathogen or a vaccination. This defense system is known as acquired immunity, tailored to particular types of invaders.

Rabies ‘vaccine’

It is difficult to pinpoint when the idea of yi du gong du became a practice, mostly because the journey to discovery was long and complicated. The earliest written record of the application of yi du gong du is found in Zhou Hou Fang (The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies) compiled by the Eastern Jin herbalist Ge Hong (284–364). This is an ancient medical book dealing with emergencies. Smallpox, scrub typhus, beriberi and chigger mites are discussed for the first time in this book. To prevent rabies, Ge’s book recommends the application of the biting dog’s brain tissue to the bite wound. Through long-term experimentation, people developed primary preventions of diseases through the use of certain ‘medicines,’ made of the mashed tissue or organs of the disease-causing objects. These ‘medicines’ can be considered the vaccine in its primitive form.

To some extent, this simple and old-fashioned measure coincides with modern medicine. Vaccines against rabies were first developed by the French chemist Louis Pasteur during the late 19th century. After he failed in cultivating the rabies virus in vitro, Pasteur found a large amount of rabies virus in the brain and spinal cords of rabid animals. Finally, he developed the rabies vaccine by growing it in the brains of rabbits.

Moxibustion

Though considered together as one important form of treatment in TCM, acupuncture and moxibustion are two different therapies. Acupuncture involves the insertion of thin needles through the patient’s skin at xue wei (acupuncture points). Moxibustion is performed by using the heat generated by burning herbal preparations to stimulate xue wei.

Moxibustion has come a long way in China. The mugwort plant is most frequently used in this therapy. The documented effectiveness of moxibustion speaks for itself. Yet, how it works is still controversial. Some correlate moxibustion with the immune system. In practice, moxibustion often causes blistering, festering and scarring, through which pathogens may gain access to the body, thus activating the immune system to rid the body of harmful invaders. During this process, the specific antigen of a pathogen will be recognized and recorded by the defense system, thus stimulating a response that targets the pathogen for destruction by the immune system.

Smallpox

For centuries smallpox was one of the world’s most-dreaded plagues. Early descriptions of the disease were documented in China as lu chuang (literally, the sores of prisoners of war), because it was said that this disease was brought to China by prisoners of war. Most believed that the disease reached China after General Ma Yuan of the Eastern Han Dynasty pacified the rebellion in the Lingnan area in southern China. In the year 44, Ma Yuan made a triumphant return. When he checked over his troops, he found that half of his soldiers had died from a plague instead of the war. This plague was generally considered to be smallpox. Smallpox had been one of the most feared forms of pestilence in ancient China. A medical book compiled during the Ming Dynasty documented that in the spring of 1534 an outbreak of smallpox had a mortality rate of up to 90%.

Efforts to combat smallpox were made by the ancient Chinese over a long period of time. People gradually found that the inoculation of ren dou (literally, human pox) could be used to protect against smallpox, the principle of which was that a healthy person could be made immune to smallpox by being exposed to the virus from an infected person.

Early practices involved dressing a child who had never been infected in the clothes from an infected child, which was called douyi fa (literally, pox-garment method). In the successful cases, the virus caused only mild infections, but induced an immune response which provided cross-protection against smallpox infection. Another technique known as doujiang fa (literally, pox-lymph method) was to dip a piece of cotton into the pus taken from the sores of an infected person and stuff it into the nose of a healthy person. Survivors could be made immune to smallpox.

These two measures were easy to perform but not to perform successfully. People continued to improve the methods of inoculation. A new technique known as hanmiao fa (literally, dry inoculum method) was to grind the scabs of a smallpox victim and blow the powder through a tube into the nose of a healthy person. People inoculated in this way would suffer a fever in seven days, a symptom which indicated the success of the inoculation. However, the powder often stimulated the nasal mucosa to secrete more mucus, causing inoculation failure.

Finally, people developed a method with the highest success rate, known as shuimiao fa (aqueous inoculum method). Shuimiao fa was performed by mixing the powder of the scabs of a smallpox victim and water together, wrapping the mixture with a thin piece of cotton into a date-seed-shaped cocoon. The cocoon was then tied up with a thread and stuffed into the nose of a healthy person, which would be removed after 12 hours.

The inoculation of ren dou was practiced in ancient China for a long time. A Qing Dynasty medical work describes smallpox inoculation as practiced in China since the Kaiyuan era of the Tang Dynasty (713–741). Tens of thousands of lives were saved. Another Qing Dynasty medical book recorded that among eight or nine thousand people who were inoculated, only a few dozen people didn’t make it. Voltaire expressed his admiration of China’s inoculation practice in his Philosophical Letters, saying, “I understand that the Chinese have had this custom for a hundred years. The example of a nation that passes for the wisest and most strictly governed in the universe is a great thing in its favor.”

The article was edited and translated from China Development Observation. Chen Zhonghai is a columnist and a scholar in history and literature.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE