Unearthed slips offer clues to the Qin Dynasty

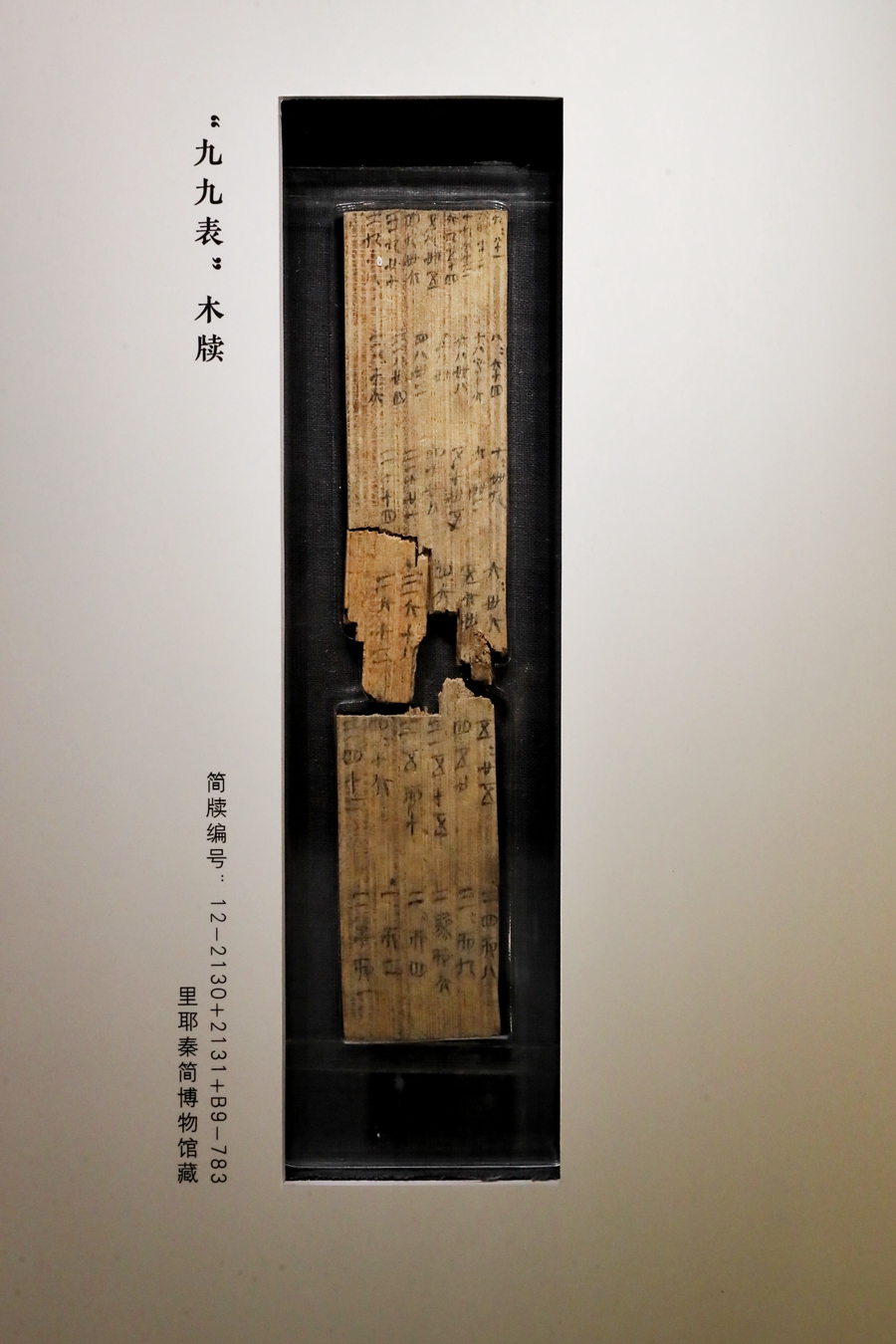

A Liye slip featuring the multiplication formula in Chinese characters Photo: CHINA DAILY

The ruins of the ancient town of Liye were discovered suddenly during the construction of a hydropower station in western Hunan Province. More than 38,000 wooden slips have been excavated from a well at this 2,200-year-old site.

Ancient town of Liye

The modern Liye Town is located in a basin on Wuling Mountain. The ruins of the ancient town were discovered in the central area of the basin, spanning over 5,500 square meters. Archaeological findings show that humans have lived in the basin since the Paleolithic era.

When it came to the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE), Liye was a military garrison of Qianling Xian (The Qin established the first two-tier administrative system in China; Jun was the principal administrative division, each subdivided into Xian), a remote xian functioning as a military fortress in Wuling Mountain. Liye was destroyed in the Western Han era (206 BCE–8).

The ancient well

Well #1 was dug in the late Warring States Period (475–221 BCE) by the people of the state of Chu. Afterward, it had been used until the Qin Dynasty, and was abandoned in the late Qin period. Archaeologists infer that this 17-meter-deep well was used for military purposes at that time. Its bottom is filled with mud and the remains of ancient people. From the well, archaeologists discovered bronze spears, iron cha (an ancient spade), jade jue (a decorative jade pendant in the shape of a ring with a slit as its central hole), jars, broken pieces of lacquerware and the coins of banliang (a kind of currency in the Qin Dynasty, which were bronze coins with square holes cut through the middle). Among all the excavations, however, the bamboo and wooden slips attracted the most attention from the public. Most of these slips were administrative documents of Qianling Xian, unfolding a panoramic view of administrative management at the xian level between 222 and 208 BCE, ranging from population, landholding and taxation to post, military, judiciary and medicine.

It should be noted that although these slips are deemed to be among the most valuable epigraphic sources on the history of the Qin today, they were dumped into the well as garbage by the Qin people. In the late Qin period, peasant’s revolts broke out and Liye fell in the subsequent national unrest. Therefore, the well was abandoned and turned into a dustbin. At the bottom of the well, these slips mixed with other garbage. The moist, enclosed space enabled them to survive through more than 2,000 years.

Qin slips

It is said that the total number of the Liye slips was large enough to change our knowledge and perceptions of the Qin’s history. The significance of the Liye slips can be viewed as rivaling that of the discovery of the Qin Shuihudi bamboo slips in 1975. The tomb where the Shuihudi slips were excavated was probably owned by a rank-and-file official, who might have worked in a judicial office. The slips, which were buried as funeral objects, were mainly judicial documents of the Qin. The Liye slips are administrative documents, helping historians to understand more about the dynasty’s burea ucracy and people’s lives. Before the discovery of the Liye slips, the earliest local government annals in Hunan Province date back to the Ming Dynasty, and written records about the past 2,000 years were previously unclear. It is through these tiny slips that people today are able to get a glimpse of this region’s past during the Qin and Han eras.

Furthermore, through the glimpses of a small town’s past, we can get a bigger picture of the Qin’s administrative divisions. Historians used to believe that the Qin had established 26 jun before they found that there were 28 jun documented in the Liye slips, while the Qin slips collected by the Yuelu Academy of Hunan University mentioned only 22 jun. After the combination of the records from the two sources and the deletion of the duplicate items, historians finally identified 37 jun established during the early Qin Dynasty. The specific information of the administritive division of the Qin has high value for supplementing and testifying historical facts. The Liye slips also record many place names at the xian level that are still in use today in the northwest of Hunan. Historians used to think that some towns in present-day Hunan were established during the reign of Gaozu of Han (ruled between 202 and 195 BCE). The Liye slips prove that these place names have been used since the Qin Dynasty.

Information on slips

In 2005, 51 slips were found during the cleaning of the moat around the ancient town of Liye. These slips, which were addressed as huban, served as the equivalent of present-day household registers. They are the oldest household registers that have ever been found in China. The basic information of householders recorded on the huban is divided into five categories, including native place, name, rank of nobility, family member and real estate. Some slips mention that when the authorities commandeered products in large scale as military supply, local governments needed to follow the orders and provide enough labor for tasks without interfering with agricultural production. It was quite challenging for the local governments at the time.

The slips also help historians to understand more about the agriculture of the Qin. At that time, land was classified into gongtian and mintian. Gongtian referred to the state-owned land, which was operated by the government with its harvest yield going to the state. Mintian was known as qianshou tian (qianshou was the general name for civilians during the Warring States Period and Qin era). Under the xingtian system (a historical system used for land ownership and distribution in the Qin Dynasty), some state-owned land was divided into small plots and distributed to qianshou. Qianshou didn’t have ownership of the land, so they couldn’t sell it, and a fixed amount of tax had to be paid to the government. For newly cultivated land, farmers could pay fewer taxes or no tax at all in the first two or three years. Most of the people farming qianshou tian were family members. Agricultural employment was also permitted. Criminals and garrison soldiers constituted the majority of farming laborers on gongtian.

There were not many types of crops at that time. People cultivated su (foxtail millet), shu (a general word for beans), wheat and rice. The cultivation of taro and meizi (proso millet) was also recorded in the slips. Ramie, oranges and lacquer trees were cultivated as cash crops by the Qin people. The slips mention details of the local agricultural practices. Because many local farmers were too poor to afford the seeds that they needed, the Qianling government put certain policies into practice to solve this problem, such as lending seeds to farmers. Archaeologists found political orders and cultural policies enacted during the Qin era from the slips. The Qin introduced a unified system of writing and addressing. For example, King Zhuangxiang of Qin was posthumously honored by his son, Qin Shi Huang, as Tai Shang Huang; the horse that was ridden by the emperor or pulled the emperor’s carriage was called Cheng Yu Ma; the emperor’s dog was called Huang Di Quan.

Information like this was written on the slips as booklets to be circulated among people. These slips were also used for easy reference when composing official documents.

Some slips demonstrate the specifics of people’s lives and provide detailed information of regional governance at the time. A set of slips record that in 214 BCE, a civilian in Yangling Xiang (xiang was a basic administrative unit under the xian) owed money to the local government and he went to Dongting Jun to perform military service without paying off his debt. Officials in Yangling didn’t know the man’s address in Dongting, thus sending an official communication to the government of Dongting Jun to ask for help. This issue reflects an advanced legal practice under Qin rule before the invention of the remittance between different areas. According to the Qin laws, if a regional government owed money to civilians, the creditors had the right to ask another regional government to pay off the debt, and vice versa.

The article was edited and translated from Guangming Daily. Zhang Chunlong is a research fellow of Library Science from Hunan Archaeology.

edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE